In the last decade or two, it has become commonplace to see the Seven Years' War as an "early modern media war", "which triggered an enormous increase in journalism". The battle for supremacy was fought not only on the battlefields, but also with the pen. Printing presses acted as weapons. This shifted the focus of perception: since then, it is not only what actually happened that is of interest, but how it is depicted, how or where these thematisations circulate and in which practices they are integrated. From this perspective, the question then arises, for example, of how a battle can be described at all and which media conditions make its visualisation possible in the first place. The researching gaze is not only directed at printed texts and images, but also at music and noisy soundscapes, buildings and room furnishings, monuments, medals, tobacco tins and much more.

I.

The reasons for this increased interest in the media can certainly be found in the present day. But it can also be based on evidence from the time of the Seven Years' War. As early as 1757, a pamphlet on the large "quantity of state publications" that flooded Germany at the time stated: "One can find no example from either ancient or modern times that a war would have occupied so many pens." And in 1763, at the end of the war, a master baker from Hanover summarised in his diary: "The number of state and other writings from this war is quite considerable, they are said to amount to over 1,000 pieces, more than 36 volumes printed in 40. It will not have been easy in older times for a war to have been waged of which the number of printed and unprinted writings is as great or greater than of this last war, which can therefore be a proof of its greatness, importance and the attention shown in it."

Our master baker has rather understated things. There were probably far more writings published between 1756 and 1763. The contemporary collection of the latest Staats-Schrifften zum Behuf der Historie des jetzigen Krieges, which appeared from the second volume onwards under the title Teutsche Kriegs-Canzley, printed a total of 1,693 documents on 18,410 pages in 18 volumes. Indexes make this enormous mass of text accessible. The war sermons, poetic texts and the quantity of local occasional writings are not included, nor are journals and newspapers. Most of the publications appeared in the first three years of the war, after which interest waned somewhat.

Johann Wilhelm von Archenholz saw this lively publication activity as a characteristic feature of both this war and his age.

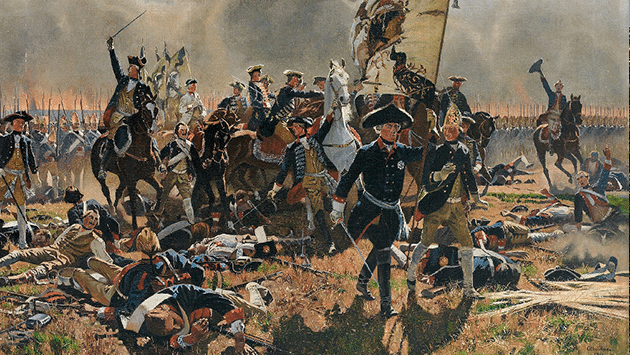

In his history of the Seven Years' War, he personalises the events: "Just as much as he [Frederick II] used his sword against his enemies, he also made use of his pen. In general, the strange mixture of numerous manifestos and murder scenes was one of the peculiarities of this extraordinary war. Everything that physical and mental strength could achieve was brought to bear against each other. Never were so many battles fought in a war, but never were so many manifestos issued as in these days of great misery. Great monarchs wanted to justify their conspicuous actions before all nations in order not to lose the respect of even those peoples whose applause they could easily do without. This was the triumph of the Enlightenment, which in these times began to spread its beneficent light over Europe."

A short essay published in the Berlinische Monatsschrift in 1784, which also paid homage to the Prussian king, helps us to understand what was meant by the "Triumph of the Enlightenment". Here, too, there is talk of "Frederick's century". Immanuel Kant's answer to the question: What is Enlightenment? can be taken for granted: Enlightenment is the "exit of man from his self-inflicted immaturity. Immaturity is the inability to use one's intellect without the guidance of another." This emancipation of the individual requires resolution and courage, and above all it requires the freedom "to make public use of one's reason in all matters." Kant understands "the public use of one's own reason" as "that which someone makes of it as a scholar before the whole audience of the reading world. The private use I call that which he may make of his reason in a certain civic post or office entrusted to him."

The process of enlightenment is linked to the role of the scholar as spokesperson and to its correlate: the "entire public of the reading world". In other words, the public sphere that Kant has in mind is based on the medium of writing, or more precisely, printing. It is the communication space of those scholars who speak "through writings to the actual public, namely the world". Here, writing, the publication, has the function of enabling universality. This is because printing makes an utterance accessible to all ("the world") and fixes it in a storage medium. This makes the process of enlightenment independent of presence in one place and time. Anyone can access anything at any time and subject it to critical scrutiny. In this sense, we are dealing with a public sphere of enlightenment with a claim to universality (a regulative idea, as we are not yet living in enlightened times). Accordingly, enlightenment would be an eminently literary matter. And the feather war is part of this, and can perhaps even be understood as a "triumph of the Enlightenment" (Archenholz), because it demonstrates the compulsion to publicly legitimise action.

Looking at the Seven Years' War, one could criticise this concentration on a privileged medium. However, it could be argued that printed matter actually dominated. Illustrated pamphlets with their combination of text and images hardly played a role any more. In pictorial journalism, maps illustrating battles in particular experienced a rise, albeit in a way that required a skilled recipient. The most famous paintings, such as Benjamin West's The Death of General James Wolfe in Quebec (1770) or Bernardo Bellotto's Dresden Ruin Paintings (The Ruins of the Church of the Holy Cross, seen from the East, 1765), were not created until after the war. The materiality of such depictions is also tied to the original and thus to a specific place, unless they were copied, produced in series or distributed through printmaking. Daniel Chodowiecki's engravings, which were probably the most popular in the 18th century, were also almost all published in the decades after the war. They owe their wide distribution to their combination with texts in calendars, which at the time achieved print runs of 10,000 - 20,000 copies; books could only dream of such numbers. The combination of text and print is complex, not only because two different printing processes are involved. A copperplate engraving only allows for around 3,000 impressions; then the plate has to be replaced. The text-heavy nature of war journalism and the absence of decorative accessories are indications of an acceleration of communication and a greater impact on a wider audience thanks to lower prices.

The statements fixed in storage media are collected in libraries and archives, in galleries or museums (today, of course, on the Internet). These institutions ensure the simultaneous presence of all utterances. To a certain extent, they plausibilise the idea of universality as Kant might have envisaged it. However, such collections tear the objects out of their contexts of use in order to use them for new compilations, for other contextualisations, even if only as evidence in a note. For historians, the task is to reconstruct the contexts of the time (of production, reception, circulation, etc.) from these remains. From this point of view, the limitations of an otherwise unlimited circulation are particularly meaningful. We are not 'in an enlightened age', but are engaged in the process of enlightenment.

The limitations of a universally conceived Enlightenment public sphere give rise to 'limited' media public spheres in their own particular way. We can track them down if we visualise what Kant did not take into account. It is precisely those facts from which he abstracted that are relevant to my topic. Firstly, Kant does not say in which language (and in which formats) people communicate. Secondly, he assumes that people can read and write, which is by no means self-evident. Thirdly, he assumes that communication serves to establish truths and obeys a rational discourse. Fourthly, Kant presupposes a fundamental equality of the actors, which is not the case in a corporative society. Fifthly, Kant ignores the problem of how the publications reach the other participants. Which media make this possible? What infrastructure is necessary for this? Which forms of distribution can be used to reach whom? On the basis of which business models can this work at all?

II.

In order to clarify the conditions for publics and propaganda, we need to look at these five aspects: the role of language, literary competences, the rhetorical strategies of communication and, above all, the specific business models of war journalism. In each of these four respects, asymmetrical relationships, i.e. inequalities, play a role that can hardly be underestimated.

Firstly, the language, or to be more precise: we have to assume multilingualism. Since the end of the 17th century, more books have been printed and traded in German than in Latin in Germany. In France and England, this change took place several decades earlier. With the replacement of Latin as the international scholarly language by national languages, the expansion of the book trade was directed towards the internal market in order to open up the communication areas constituted by the national lingua franca. With language, the rules changed as to who belonged and who did not, i.e. inclusion and exclusion. Under these conditions, it is to be expected that dominions that encompassed several language areas were faced with particular problems. At the same time, competition arose between the emerging national cultures for a leading role that was able to represent modernity in normative terms as opposed to the model of antiquity.

France had occupied this position since the 17th century. The upper classes, especially the courtly aristocracy, spoke French and orientated themselves towards French culture; at the Prussian court much more so than with the Habsburgs in Vienna. Anyone who wanted to reach a European audience had to write in French. Even after the Seven Years' War, English did not play an important role as an international lingua franca; the influence of English culture, which should not be underestimated, required translation.

While French was socially marked as the language of the nobility, scholars were recognised by Latin. However, this international lingua franca steadily lost importance. However, this did not apply to the field of higher, academic education, which became increasingly important as a prerequisite for higher civil service. Knowledge of Latin was still required here; accordingly, one can assume that most authors had the relevant expertise. The vast majority of the population used dialects for communication, the range of which was regionally limited. High German, which was primarily a literary language, served as the national lingua franca. In the words of the Enlightenment philosopher Christian Garve: "The language of books is, in all provinces, better known even to the countryman than the vernacular of one province is in another." In national terms, we are dealing with a printed language area whose language first had to be formed (i.e. regulated, disciplined, cultivated) and enforced. Scholarly popularisation efforts played a role in its spread that should not be underestimated.

The linguistic practice of scholars and administrators (chancery language) proved to be an obstacle, because they orientated themselves towards Latin in word formation and syntax and thus produced endlessly convoluted but correct sentences with a high proportion of foreign words. This makes it difficult to understand a considerable part of the war journalism, which also had little appeal to a broader readership due to its typographical design (closely set lead deserts). If you wanted to reach the majority of the population, you had to rely on dialects and orality; this limited the impact to regional or local areas. Anyone who spoke High German was regarded as an educated city dweller.

Secondly, participation in literary culture required literacy, or more precisely: literalisation, because it was about much more than just spelling. It is doubtful whether the ability to sign, which serves as an indicator of literacy, was sufficient to read newspapers or pamphlets. It required at least a rudimentary education, which did not necessarily have to be taught at school. It is difficult to say what proportion of the population participated in print culture around 1750: there were clear differences between town and country, between the sexes and denominations, between poor and rich areas, between north and south.

However, the (aristocratic, scholarly, bourgeois) upper classes can be considered fully literate. However, the potential for an expansion of literary communication should not be underestimated. Tapping into this potential was a difficult task. Accordingly, many print products in the 18th century were addressed to "scholars and unscholars" or to "readers from all classes". However, this should not be understood to mean that unlearned people and all classes read, but that there were readers among the unlearned and in all classes. Expanding the audience was initially a laborious business, but in the last third of the 18th century, i.e. after the Seven Years' War, it developed a great deal of momentum of its own.

Reading is one thing, writing is another. At first glance, authorship appears to be more demanding. However, it should be borne in mind that in the early modern period, both school and university classes taught writing in the correct form, whereas in the modern period ('after 1800'), education focussed on reading and text comprehension. Teaching took place within the framework of rhetoric, which was orientated towards the speaker, not the listener. As a rule, ancient or French classics served as models. For example, when Das bedrängte Sachsen lamented its situation in a pamphlet in Alexandrine, a verse form was used that was characteristic of high literature (tragedies, epics). Such formal choices refer to the scholarly context. Only the commercialisation of the book market will dissolve this scholarly context of communication, or more precisely: it will open it up. Jürgen Habermas has emphatically pointed this out. This changed the role of the recipients. In economic terms, they gained in importance as buyers, as consumers. The reading public can no longer be thought of as a simple resonance chamber for rhetorical or propagandistic strategies. The abundance of propagandistic, partisan literature during the Seven Years' War in particular urged the reader to become more active. They had to learn to deal more critically with the information on offer.

In the words of a contemporary observer: "You can see from this that the newspapers 60 years ago were exactly what they are now, namely a mixture of truth and lies, without most of the newspaper writers themselves being much to blame. The true news, coming from one side or the other, has a certain cover around it, in that too little is said on one side and too much on the other. Here you have the grains together with the chaff. A sensible reader already knows how to separate the grains. The light chaff is easily blown away by the wind. [...]."

Thirdly, rhetoric. Kant did not appreciate it at all. However, its importance in the 18th century can hardly be overestimated. It teaches how to communicate appropriately and successfully. The aim is always to achieve an effect. You want to achieve something, arouse emotions, convince or persuade someone. Since such strategic communication was considered normal, it is difficult to clearly distinguish propaganda from it. It is easy, for example, to show from the reporting on battles that one's own losses have been minimised and the gains exaggerated. But a fact check misses the point. Such reports pursued a political intention that could be clever or not so clever. The "wisdom of the state" could in fact require the whitewashing of a defeat "if the misfortune has an influence on the nation's credit and if it is necessary to encourage the people and their allies or to keep them steadfast in the party."

Rhetoric functions as a general theory of communication. It is based on structural orality. Regardless of writing and printing, it is based on the model of a speech in front of a present addressee. The audience is therefore not thought of as anonymous and heterogeneous, but as homogeneous and familiar. People know each other, so the effect can be calculated. Self-contained circles that interact with each other according to certain rules of discourse, such as at court or in a republic of scholars, are assumed. It is not assumed that all participants are equal; rather, there is a great sensitivity to differences in rank and social hierarchies. It is always about appropriate communication that knows how to adapt to the requirements of a stratificationally differentiated society.

III.

Finally, fourthly, economics. Reproducing writings in print requires a division of labour and cooperation. The pen warrior needs a printer who is often also a publisher and bookseller. In technical terms, relatively little has changed in this profession since Gutenberg's invention in the 15th century. Decisive innovations only became established after the Seven Years' War, first in England and then in Germany. The structural change discussed below can therefore not be explained technologically by recourse to a media hard ware. In contrast, the business models on which the production and distribution of print media are based deserve greater attention.

Reproducing fonts in print costs money. The most important items for the calculation are: typesetting, printing, paper and distribution. Various aspects need to be taken into account when calculating the costs. The scope (number of characters) and degree of difficulty (typography) play a decisive role for typesetting, the scope and print run also play a role for printing and paper, while postage (weight, distances) and trading conditions are the main factors for distribution. The relationships between the cost factors shift depending on the size, print run and distribution area: With large print runs, the proportion of typesetting costs decreases, while the paper price becomes more important. When supplying a wide sales area, the transport costs and thus the distribution costs increase.

Under these conditions, the costs for short texts in small print runs for a local or regional market are particularly low. This segment is likely to have been particularly well represented among the publications of interest to us. It can also be assumed that the booksellers calculated very carefully in order to reprint if necessary. Speculating on high sales, on the other hand, was a highly risky business. For England, Tilman Winkler differentiated between very small print runs (130-550 copies), a normal market (500-1,500 copies) and a bestseller market (from 1,000, more likely 2,000 copies as a starting print run). Different rules apply to calendars, textbooks and how-to literature as well as newspapers and magazines. We are still a long way from a mass market (i.e. mass media) in the modern sense. How can propaganda or war journalism function under these conditions? What motivates the authors if they cannot count on (significant) fees? How can co-operation and financing be combined to create viable business models in such circumstances?

From this point of view, it is worth taking a closer look at different types of propaganda writings with regard to their business models. How is the production and distribution of these publications organised? And who bears the costs? The typology of state pamphlets proposed by Johann Friedrich Seyfart in a pamphlet in 1757 can serve as a starting point for the following considerations. He distinguishes between three genres: In the first, the state (the regent, the government) is in a sense the author, in whose name ministers or civil servants write texts. In the second, scholars (political scientists) are commissioned by the government to write texts that appear under their names and not under the name of the person who commissioned them. The third type of state writings comes from writers who work on their own initiative. As a fourth business model, we must add newspapers, which play an important special role. Incidentally, they are not even mentioned in Seyfart's discussion.

The first business model is less spectacular because it most closely confirms our expectations about political propaganda. Everything is more or less in one hand, which also has considerable organisational and financial resources at its disposal. A government commissions its civil servants to write relevant texts, if not the ministers or the regent himself. These are authorised writings that often undergo several checks before publication. This authority protects against 'uncalled for' criticism. The other party was responsible for this: a dispute between great lords.

Reproduction could be carried out by a state printing works. In the 18th century, however, privileged court book printers were used so that their professionalism in production and distribution could be utilised. This also transferred some of the risk to the bookseller. In many cases, the publication of state publications did not pay off for the court book printers, but the privileges usually associated with such orders (such as the monopoly on the printing of calendars or schoolbooks) meant that the business proved to be profitable. An outstanding example of this in Vienna is Thomas Trattner, who quickly rose to become the largest and richest bookseller in the Habsburg Empire.

In Germany, the vast majority of state publications during the Seven Years' War were not addressed to the country's own population, but to the imperial public, i.e. the other rulers in the Old Empire. This facilitated distribution, as the permanent Imperial Diet in Regensburg served as a news hub. The publications were distributed to the diplomatic representatives gathered there, who then passed them on to their courts. Prussia's attempt at the beginning of the war to interpret the conflict with Vienna as a religious war was presumably primarily aimed at the Imperial Diet in order to secure the support of all Protestant powers there - but without success.

In the first business model, all links in the chain, from production to printing to distribution, are largely subject to centralised control, so that one could speak of an absolutist public sphere or a journalistic cabinet war. A wide variety of text types enabled skilled pens to perform sophisticated tactical and strategic manoeuvres, which an equally disciplined opponent observed closely in order to respond with his troops. Such state writings "in the name of the courts [evoked] the counter-answers, counter-conceptions, legal illuminations or examinations" of the other courts. This "exchange of arguments in written form [took] account of the legalisation and culture of discussion in the imperial system". However, it was primarily a relatively small functional elite of the estates that was active here. If the ruler wanted to reach his own people, this was rarely done via the print medium. Instead, he utilised the infrastructure of the church by prescribing festive services and sermon topics. In this way, the largest audience in terms of numbers was addressed.

Even if the cabinets formed the centres of gravity of this political propaganda, they did not exercise complete control over the communication. This was simply due to the fact that messages in storage media have a tendency to become independent because it cannot be ruled out that they will also appear in contexts other than those intended. The state documents were also disseminated via newspaper news. However, some of these government declarations were expected to have a much greater resonance. This applies, for example, to the texts with which Frederick II legitimised the attack on Saxony in 1756. The fact that the original French text was published more frequently than its German translation (eight to five) says something about the recipients.

The second business model also meets our expectations. The government 'buys' scientific expertise by commissioning scholars or statesmen to write legal opinions or political statements. It can be assumed that the governments covered (at least part of) the costs of production and distribution. This was also a specialised discourse that was largely supported by a small functional elite. One can speak of covert propaganda because the clients were not mentioned in order to create the impression of an impartial statement.

The texts appeared as contributions to scholarly communication. As a result, they were more strongly criticised by other scholars, as argumentative and polemical debate was part of the constitution of the respublica litteraria. For the author, this was about his reputation as a scholar. For the cabinets (courts), it was an opportunity to test the viability of claims and arguments without being directly involved. In doing so, however, they were subject to the rules of scholarly communication practice, which obeyed a much slower time rhythm. This was partly due to the dissemination of writings, which was taken over by the book trade, which had developed special practices in the early modern period.

In order to minimise the risks involved in marketing scholarly writings, an exchange practice had become established in the intermediate trade. Printed sheets were exchanged for printed sheets at the fairs, which took place at the same time in Europe, so that the books could reach the scattered members of the scholarly republic over great geographical distances. Money was not collected until the final sale. This practice, which was very efficient over a long period of time, presupposed that all publications were of roughly equal value and therefore convertible (like educational qualifications in the Bologna process) and that they were relatively durable goods, as this form of distribution was time-consuming.

Above all, however, the barter trade characterised the infrastructure of this industry because it required booksellers to be both publishers and printers in order to produce the goods needed for barter themselves. In this closed system, somewhat different rules applied to occasional publications aimed at topicality, such as propaganda texts. Here, cash sales (for money) played a much greater role, i.e. demand became the determining factor. This in no way automatically led to higher print runs. The advantage was rather in being able to react more flexibly to local and regional markets as well as to special audience interests.

IV.

This opened up a space for our third business model. The authors here are writers who act on their own initiative. Seyfart attributes ambition, self-interest and passion to them, but this anthropological motivation, however accurate it may be, explains little. A social localisation of the authors does not help much either, because they were generally academically socialised scholars, although it is noticeable that they published particularly frequently in the precarious phase between their studies and permanent employment. This group of writers, who were more or less independent of the state, is of particular interest to us because their production was much more diverse in terms of content and form.

These were occasional publications that responded to current events, debates and economic cycles. Here, too, it is worth paying attention to the economics. It can be assumed that many of these occasional pamphlets could not count on large sales. In form and content, they were often modelled on state writings. They took part in scholarly debates. They disseminated victory announcements in the form of poems and printed versions of sermons. High print runs were hardly achievable. Consequently, the fees were probably rather low.

So what was the benefit for the writers? What motivated him to get involved? To answer this question, it is worth taking a brief excursion into the realms of big politics, which can provide us with insights into this third business model.

In 1760, the French government pulled off a propaganda coup. In any case, it can be assumed that it was the French government that ensured that a three-volume edition of Frederick II's poetic works was published in Amsterdam. Due to the author's prominence alone, but even more so because of the scandalous content, the volumes met with great interest from the public. Several editions were quickly sold. It was a propaganda success for the French court because the Prussian king made very derogatory and offensive remarks about his allies in his texts and presented himself as a mocker of religion and a libertine. In doing so, he discredited himself and his allies and sympathisers in France and especially in England, on whose financial support he was more dependent than ever before. The Prussian government could do little to counter this. It limited itself to claiming that a falsified, unauthorised edition had been published, to which it then responded with its own ('purified') version.

However, this propaganda campaign is not only revealing from a political point of view, but also with regard to the handling of texts. The Versailles court 'only' organised the publication of the edition and left its distribution to the international book market. There were no costs for the government, while the book trade actually profited considerably, as did the newspapers and magazines, which reported extensively on this process and the scandalous passages. Propaganda utilised the commercial market for books and news by feeding texts into this media system. This business model differed significantly from the one in which the work edition had first appeared ten years earlier. Frederick II had not only compiled his own poetic works himself and had them printed in very small numbers, but was also responsible for their distribution. Only very few selected persons from his closest circle ('friends') received the volumes from him with the obligation to treat the contents confidentially, i.e. to keep them secret. In the event of his death, the books were to be returned to the king, who presented himself as a man of letters in the arcane realm of power. Consequently, one only came into possession of his works through a special favour from the ruler. The distribution of the publication followed the logic of gift exchange. Whoever received the edition was honoured for their (also future) services and loyalties. At the same time, the king attempted to maintain absolute control over his texts in this way - ultimately in vain.

Gift exchange not only works from the top down, but is also practised - far more frequently - from the bottom up. It is then a matter of showing others a favour in order to receive another in return. This corresponds to the logic of reciprocal exchange in the republic of scholars as well as the asymmetrical relationships at court. As a rule, more is invested from below - and less is donated from above. It can be assumed that a large proportion of the occasional writings operated in this mode. The authors produced texts in order to draw attention to their own competences and to testify to their own qualities in competition with others.

As this competition took place within a framework determined by clientele or patronage relationships, it was advisable to observe the prevailing rules of discourse. In other words, people imitated the established formats and patterns and tried to outdo them: imitatio et aemulatio. In this respect, most of the occasional writings revolved around the centres of gravity of courtly politics and scholarship. This was a condition for success in this third business model. The writers behaved in accordance with the system as long as they were aimed at higher-ranking patrons and not at a paying audience.

The commercialisation of the book market opened up scope for freedom when royalties were paid that authors could live on. Until the end of the 18th century, however, such a precarious existence for a 'freelance' writer was by no means desirable. Instead, most authors endeavoured to find a permanent position in the state or church service. With their contributions to the discourse and their printed sermons, they applied for an office or a promotion, or even just to attract attention. In this way, they contributed to propaganda and to the expansion of the print market and the necessary infrastructure. According to the logic of this third business model, however, it was not a question of large sales successes; rather, even the smallest print runs fulfilled the purpose of being seen in print. In terms of the costs involved, very small print runs were far less risky. Even the royalty could be waived, even an author's own 'printing subsidy' could be worthwhile if it gave them a competitive advantage. It is therefore quite likely that some sermons found more listeners than their printed readers; but in the printed version they probably reached more 'exclusive' recipients.

The careers that were possible under patronage conditions can be illustrated by an unusual example. Anna Louisa Karsch came from the poorest of backgrounds. She had the extraordinary, almost ingenious ability to write poetry off the cuff. All you had to do was give her a topic, a few words or phrases and she would produce perfectly formed verses in no time at all. She attracted attention with printed occasional poems about city fires and the victories of Frederick II and found patrons who were not stingy with gifts, initially among the country clergy, then in aristocratic circles and at the court of the Prussian queen. Finally, she was even received by Frederick II, from whom she was able to persuade him to give her a house; after much insistence, this promise was honoured by King Frederick William II. In literary circles, this poet was regarded as an admired natural genius whose 'ingenium' confirmed the latest theories of poetry. On the book market, however, she had far less success.

V.

If Seyfart did not include newspaper writers in his typology of authors of state writings, it may have been because newspapers had their own (a fourth) business model. Newspapers were a child of the postal service, and this distinguished them from magazines and journals, which originated as periodicals within the respublica litteraria. Newspapers have therefore received correspondingly little attention in the traditional history of the book trade. Newspapers were used to disseminate news, which was initially communicated via letters that were then bundled at the nodes of the postal routes and reproduced by printing. The postal network therefore plays a central role here. This origin still determined the layout of newspapers in the mid-18th century. Instead of headlines, there were location and date details that referred to the origin of the news, the location of the correspondent, and not to the reported events. News from India could therefore be found under Lisbon or Halle because the relevant information had arrived there.

The news items were printed in the order in which they arrived at the editorial office, not according to the chronology of events or even in terms of their relevance. This practice served the purpose of authentication. It also says something about postal connections, distances and speeds. On average, the events reported were around a fortnight ago. Messengers on horseback, letters and rumours were faster. The advantage of newspapers lay less in their timeliness than in the uniform distribution of a flow of news. This medium thus provided a constantly updated level of knowledge about world events. We can therefore speak of a media reality that could serve as a generalised frame of reference for communication. In this sense, the letters of contemporaries often contain references to reading newspapers, which assumed a level of knowledge that was generally known in order to provide further information or commentary. Letters and newspapers arrived in the same post.

Due to their periodic publication, often on the two or three postal days of the week, newspapers were subject to much greater control than pamphlets, for example. State censorship was the rule, and its justification was hardly disputed in the 18th century. Import bans on foreign ('foreign') newspapers also served to control the flow of news. However, this could only restrict the dissemination of information to a limited extent because other newspapers (especially those in Hamburg) also disseminated the news. Import bans were more likely to cause economic damage to unwelcome competitors. Johann Heinrich Gottlob von Justi called newspapers that reported on world events "state newspapers", whose "patheylichkeit" was generally recognised. This would not have changed during the Seven Years' War, because even in the War of the Spanish Succession sixty years earlier, newspapers had been "regarded as nothing more than weapons of the pen [...] which the warring parties used against each other as well as the ordinary weapons of war."

And then he added: "If we could doubt this state of most newspapers for a moment, we would be sufficiently convinced of it by what has happened in the present period. Do we not see that different newspapers are at war with each other, and assail each other with all sorts of insinuations and falsehoods? If some do not evidently take sides with the belligerents, their partisanship is evident everywhere."

The public was aware of this partisanship of the newspapers. Indeed, it may well have contributed to the success of this media format, as it allowed people to obtain reasonably reliable information about the position of a government or court. The detailed court reporting also speaks in favour of this. It was not the individual organ, but the media system that provided reliable information about the political situation in the world. However, this required reading various newspapers. Even if this was not possible, reading newspapers encouraged a critical view of the reported events. People learnt how to deal with the perspective refraction of perception.

Here too, the reading public consisted largely of the relatively small circle of a learned and educated upper class with the gravitational centres of courtly society and the republic of scholars. This is confirmed by the circulation figures, which around 1750 were on average still more in the normal market range (500-1,500 copies) and only expanded strongly at the end of the 18th century. Even if one takes into account that print media products had far more readers than buyers, that they were displayed in coffee houses and inns or circulated among the public, their reach should not be overestimated. However, it is just as important to realise that more and more sources of information were available to the ruling elites. The complaints about the abundance of publications point to this. Above all, however, they practised observing politics, whereby the perspective of the courts and governments dominated.

VI.

The interim conclusion is as follows: Nothing seriously new in the Seven Years' War. Relevant changes only occurred when a 'new' larger audience was gained, when a 'new' centre of gravity emerged with a commercial market for print products, which relativised the influence of the court or state and scholarship by creating space for a fifth business model. Here it is worth taking a brief look at French and English conditions, which in the middle of the 18th century were still several decades ahead of Germany.

Both France and England had major cities, Paris and London, as their centres, which, with a population of around 500,000, were about five times the size of Vienna or Berlin. This concentration of population was accompanied by a considerable concentration of communication. Not only the relatively short distances proved to be an advantage for the book market, but also the link between the print media and the interactions in the salons, coffee houses, pubs, clubs, etc. In this dense network of resonance spaces for printed matter, competing groups and positions formed in a diversity for which there was as good as no equivalent in the German-speaking world.

England and France differed in the way this plurality was dealt with. Since the end of the 17th century, there had been extensive freedom of speech and the press in England. As there were hardly any state restrictions, disputes were fought out on the market, in a "war of words" (Winkler), which was also about political and economic advantages. France, on the other hand, had relatively strict censorship laws, although they were applied far less strictly. Contrary to appearances, we are no longer dealing with an absolutist public sphere here either, but with a thoroughly pluralistic one.

At the top, three centres competed with each other: the court in Versailles, the Parisian salons and the Enlightenment philosophers around the Encyclopédie. Frederick II acted in a correspondingly differentiated manner: in terms of ceremonial, he orientated himself more towards Versailles, whereas in terms of culture, he followed the Enlightenment philosophers. Beneath this high culture, things were also boiling in Paris. As French was also the European lingua franca of the upper classes, there was a lively literary production outside France, which forced its way onto the French market from abroad. In the Netherlands in particular, and especially in Amsterdam, much of what was banned in France was printed and smuggled into the country without encountering a language barrier.

These relatively pluralistic public spheres in France and Great Britain meant that propaganda always had to have at least two target audiences in mind: the enemy or ally on the outside and the opposition at home on the inside. This resulted in an interweaving of international and national publicity. This can also be illustrated by the example of the aforementioned publication of Frederick II's poetic works: The publication took place in the original French language in the Netherlands, i.e. in a neutral foreign country, and was aimed at an international audience. The intention was firstly to expose the Prussian king as an opponent of the war, secondly to weaken his English supporters and thus his creditworthiness, and thirdly to discredit the French Enlightenment philosophers who sympathised with him.

In general, the example of Frederick's reception in Britain and France can be used to show how the Prussian king was also used for domestic political purposes, for example by comparing the successful general with far less fortunate British military leaders or by contrasting the enlightened Prussian monarch with the French royal court. Common national stereotypes, which were sharpened by the conflict, served as weapons for these national and international battles of interpretation. The British thus defined themselves in opposition to the French and vice versa. This patriotic or national semantics produces strong generalisations that encourage, not to say force, identification.

VII.

In contrast to the Anglo-French conflict, the German war did not only take place in the country, but there were many more political centres in the empire; they were the most important addressees of war journalism. The print medium primarily served "the mutual information of the European courts and their political ruling classes". In order to relativise the dominance of an absolutist public sphere with the two gravitational centres of court and scholarship, it was necessary to give the book trade greater independence from the state and the republic of scholars. The prerequisite for structural change was an expansion of the public, an increase in demand. In other words, the market had to be strengthened in order to establish a fifth business model. What needed to be considered in order to be successful on the 'free' market?

Firstly, it should be noted that the number of books traded at the Leipzig Easter Fairs tripled between 1740 and 1800. The highest growth rates occurred in the last decades of the century. Archenholz considered this to be a consequence of the war, and much of the research on war journalism has followed his lead. If this were the case, expansion should have ended with the war. The opposite is the case. It is therefore advisable to turn the perspective around and look at the development of the media rather than the war. Then the astonishment at the quantity of war journalism appears to be merely a prelude to the debates about writing mania and reading addiction in the 1770s; the content and formats have changed, not media consumption. The expansion of the German book market in the 18th century was associated with a shift in market shares. For example, the share of theological writings fell from 38.5 % to 13.6 % between 1740 and 1800, while in the same period fiction (fine sciences and arts) increased its share from 5.8 % to 21.5 %, and this - as already mentioned - with a tripling of total production. Real knowledge (agriculture, trade, education, natural sciences, etc.) also benefited from the structural change. The loss of importance of traditional scholarship can also be seen in the fact that the novel became the predominant genre in the field of fine literature; around 1800, more than half of the titles in this segment were in a genre that was often not even mentioned in contemporary poetry textbooks.

The popular formats acted as a driving force in the structural change of the book trade and thus the public sphere. As before, the producers of these marketable goods were mostly academically educated men. Unlike before, however, they no longer imitated what the normative genre poetics dictated, but rather what was successful on the market. In the form of the moral weeklies, the death dialogues, the Robinsonades, the epistolary novels, the sensitive love stories and dramas, these were almost all formats for which England and France had provided the models. If we want to name the characteristics of success on a somewhat more abstract level, these would be: firstly, the invention of generalisable characters that invite identification. These could be individuals, but also collectives, e.g. imagined communities such as nations, the bourgeoisie or humanity. Secondly, the fictional actors entered into relationships with each other in the form of conflicts or dialogues in order to illustrate the different positions through contrasting relationships. Thirdly, a more or less dramatic plot was set in motion, which could be developed narratively in stories. Fourthly, the debates touched the heart, they aroused emotions. Fifthly, sympathy and antipathy, virtue and vice were used to control the effect.

On this basis, it would not be difficult to show why the Prussian king had such high popularity ratings. We had a prominent actor (or more precisely: the image of an actor disseminated by the media) who was in an existential conflict, acting as a general and fighting against almost overpowering opponents. At the same time, he also asserted himself intellectually in the debate with his opponents. Even during the war, but especially afterwards, this king was familiarised in numerous anecdotes and engravings. All of this attracted public attention, stimulated further production, aroused the public's emotions and provoked judgement. It was difficult to maintain neutrality here. - At this point, one could consider what an image strategy for Maria Theresa would have looked like under these conditions and with the given raw material. One would then realise that corresponding considerations had already been implemented in the 18th century.

Not only did the modelling of the images of rulers follow popular patterns, they also influenced the state writings. Roughly estimated, around 10-15 % of all titles listed in the Teutsche Kriegs-Canzley operate with fictitious narrator roles. They present themselves as letters from a father, a friend, a traveller, a merchant, an officer, a Viennese-minded person, etc., and they are addressed to recipients who remain just as general and undefined.

These are characters who are characterised by a few distinctive features. They are private individuals who observe and comment on the events of the war and its journalistic echo. They appear trustworthy as fathers or friends and worldly-wise as travellers or merchants. They always remain anonymous. In contrast, the vast majority of state writings in the narrower sense name historically verifiable authors whose political, legal or military positions authorised their statements. It is therefore essential to mention the name and rank in these texts. The situation is different with literaryised publications. This is explained here using a rather unusual example.

In the memory of the press angel to his journeyman printer because of his writing about the writings of the Prussian publicists, an object speaks: a lever used in letterpress printing. Anyone who is familiar with Aesop's art and fables, i.e. who knows his way around literature, will not be surprised when animals or objects take the floor. "Even the public will admire the fact that a press angel speaks as little as it is strange to see such learned writing from a journeyman printer".

In contrast to authentic authorship, where a person vouches for their statements with their name, rank and reputation, fictitious speaker roles legitimise themselves solely through their text. "The world is used to deducing the author's status from the way they think and speak."

That is why it does not matter who you actually are, whether you are a journeyman printer or a pressman, but how and what you say, i.e. whether you follow the standards that apply in the literary world: "It is therefore most necessary that one should at all times think nobly, that one should think nobly, and never let a base notion escape. Remember this as often as you want to write. Always call yourself a journeyman printer or tailor. Be they really are. If you give your thoughts a noble vigour, everyone will look for a great scholar behind the larva."

This constitutes a communication space in which everyone can participate, regardless of their actual social position, as long as they submit to the rules of discourse. These are the rules of the socially opening scholarly world. The members of this respublica litteraria are characterised by their independence and freedom. "A servant may not think as freely as a master. A kind of servility must shine forth from all his actions. He must accustom himself to it, if he does not wish to be thought dissolute and spoil his happiness. This habit always clings to him. He betrays his position everywhere." Therefore, the Pressbengel appears "like a gentleman", like a scholar who presents himself to a larger audience; Kant would say: the 'world'.

The Pressbengel demonstrates his oratory skills by criticising other texts, initially that of "Buchdrucker-Gesellen", but subsequently also more than ten other publications that also make use of fictionalised speakers. The focus here is on the validity of the argumentation as well as on questions of expression (coarseness, grammatical correctness, stylistic elegance). Through such a critical debate - which is characteristic of these texts - the relationships between the aforementioned texts are condensed into a discussion context that asserts its independence from the politically authorised state writings. One could speak here of a reasoning public that observes and comments on political and military events without wanting to participate in power.

Fictionalisation helps the reading audience to orientate themselves better in the real world by putting the multitude of accessible information into an orderly context. In the texts, this is achieved by the narrator characters, who are not above things, but are part of the action, who certainly take sides, but who must convincingly defend their position to the audience in the face of other opinions. In this exercise in perspective perception, the typified figures offer the much more individualised recipients a broad surface for identification.

The critical reasoning, which even the propagandists had to make use of, was one of the great achievements of this type of war journalism; the other was the popular and pragmatic writing of contemporary history. Here, too, the authors react to the volume of reports in newspapers and pamphlets and to the public's lack of time to process this news. So a 'friend' takes over this business for a 'friend' and is extremely successful with it.

The pamphlet Schreiben eines Freundes aus Sachsen an seinen Freund in W. über den gegenwärtigen Zustand des Krieges in Teutschland (A letter from a friend in Saxony to his friend in W. on the current state of the war in Germany) is published in 24 instalments within two years alone, before a second season begins, which brings it to 25 instalments. An occasional pamphlet becomes a periodical, or more precisely: a work in instalments, which appears in two volumes at the end in 1761. In the preface, the author justifies this method of publication on the one hand with the topicality of his reports, and on the other with the fact that "not everyone can buy great historical works and yet this war account is worthy enough to be brought to children and children's children by the poor man, so that they may still recognise the great finger of God in these dangerous times and not despair where they should also experience such gloomy days and years. Finally, it has been written so that the eager lover of such war history will not be too hard on himself if he does not like to or cannot spend much time on it at once. He has therefore had the opportunity to acquire a history at very little cost within 6 years, which provides all the incidents in the most faithful way."

The delivery of a work in individual booklets at a low price so that anyone can buy it is a reference to the business model of colportage, which was used to reach a mass audience with conversation encyclopaedias and novels in the 19th century.

Christoph Gottlieb Richter, whose anonymously published Gespräche im Reiche der Todten (Conversations in the Realm of the Dead) ran to fifty booklets of 50-60 pages each between 1757 and 1763, could also be sure of constant demand. Each of these booklets featured a hand-coloured map of a battle, a meeting or a siege. It was therefore a rather high-quality product; in this respect it differed from reprints. Here, too, the individual booklets were combined to form books which, with indexes, were suitable as reference works. Richter drew on a literary tradition (Lukian, Fontenelle, Faßmann) when he had famous actors talk about current events after their death under the special conditions of the afterlife. In the realm of the dead, one no longer has to pretend and pursue one's own interests; one could speak of a communication situation free of domination.

The dialogue has the technical advantage that it allows the characters to speak for themselves. This not only creates the appearance of objectivity, but also allows the different views of the warring parties to be heard without a mediating narrator intervening. As on a stage, the characters expose themselves to observation and the audience can form their own judgement.

The "republican freedom of the reading public" (Schiller) is preserved: "It is not possible, when two people talk about the same thing, that the reasons of one do not outweigh those of the other. The judgement on which side they are strongest belongs to the reader, and no power on earth can deprive him of this judgement, as long as he keeps this gift from heaven, so that he does not forget his nearer duties in the process."

The decision to choose famous and high-ranking interviewees is justified by the fact that they are well-known characters who are known to have served their sovereigns faithfully and can therefore convincingly represent their position. Richter claims to have written the fictitious interview on the basis of state documents and newspaper reports.

The aristocratic upper class can also be replaced by ordinary people. This is the case, for example, in the weekly Der Sächsische Bauern von jetzigem Kriege redende Französische Soldat, which was published in Merseburg from August 1757 to September 1758. The constellation of figures chosen here is revealing. A Saxon farmer talks to a French soldier who turns out to be from Frankfurt. France and Saxony were allies. There was no sympathy for the Prussian army, but their king was nevertheless treated with respect. The townspeople spoke High German, the villagers dialect. This probably limited the magazine's reach to the regional market. Through the fictional protagonists, the weekly magazine signalled that it was not only aimed at an uneducated audience, but also took their view of events into account. It is about inclusion. Everyone should be included in the perception, in the texts, in the literary market, in a larger public that is pluralising.

The most famous literary participant in the war must also be seen from this point of view: Gleim's Prussian Grenadier. This participating observer or observing participant is the most radical design of a fictional figure, and this radicalisation took place in the field of poetry. Here, too, we are dealing with a 'common man', although his songs belong to the higher literary segment. Despite the popularity that this figure quickly gained at the time, it can be assumed that Prussian soldiers were not his primary target audience, but rather the many feathered warriors. With his poetic fictional character, Gleim was also responding to a problem of representation: how could the deeds of the Prussian king be transformed into poetry in order to ensure his lasting fame? The ancient constellation of Emperor Augustus and Horace served as a model for this. Archenholz also followed this pattern when he predicted a period of cultural prosperity as a result of the civil war. From this perspective, it was also about acquiring fame as the author of a period of literary splendour and at the same time enhancing the social reputation of literature. Before Gleim himself became active, he urged Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Ewald von Kleist and his friend and translator of Horace, Karl Wilhelm Ramler, to write an ode to Frederick II.

As a modern Tyrtäus, once again a literary role-playing game, Gleim did not fall back on an ancient pattern, however, but used a form of folk song imported from England, the Chevy-Chase stanza. The artificial simplicity lowered the reception requirements and increased the potential for inclusion. The Chevy-Chase stanza was far more convincing than, for example, the (more than justified) laments of Das bedrängte Sachsen written in Alexandrine verse. This choice of form implied that the role of narrator should be played by a man of the common people. With the invention of the Prussian grenadier, Gleim anticipated the trick that Walter Scott would use decades later in his historical novel, namely to portray the great story, the story of the greats, for a 'bourgeois' audience from the perspective of a middle-class hero.

This gave Gleim the opportunity to glorify his king. His grenadier must speak as a free man. As a subject of Frederick II, his eulogy loses credibility. It is precisely this independence that cannot please the Prussian king, no matter how much his soldier sings his praises. This constellation created a patriotic identification potential for a broad, pro-Prussian audience, which forced the other side to react accordingly.

Gleim seems to have been so fascinated by his own invention that he spelt out this role until it reached its limits and exceeded them. He had the grenadier fight in the various battles, becoming emotionally aroused in the process until he fell into a lust for murder that turned him into a monster. In the Prussian victory song after the Battle of Lißa on 5 December 1757, Gleim (or rather his grenadier) obviously realised this himself when, after the verses: "We, men, shouted in battle, / Die dogs! Men to", he asked the war muses to be silent:

"But muse of war! Do not sing

The whole human battle;

Cancel the terrible poem,

and say: Night has fallen."

After the Battle of Zorndorf, Gleim had to be seriously admonished by Lessing because the grenadier, standing on piles of corpses, legitimised his rage by saying that the "Callmucken and Cosacken" were savages "who have not yet become human beings". Humanity reaches its limits. With the assertion of humanity as a universal formula for inclusion, the opponent becomes the inhuman, who is now preferably located at the borders of the enlightened, civilised world, but who is also to be found in the educated. Literature makes it visible. As an actor, the Prussian grenadier also symbolises this, one wants to take part in the war. With its willingness to die - and kill - for the fatherland, literature claims an active role in society. In this respect, the Berlin Enlightenment was one of the winners of the Seven Years' War. After the war, the Prussian metropolis became the cultural centre of the German-speaking world. The Prussian king had no sympathy for this triumphant advance.