Let's start with a quote from Voltaire: "Ces deux nations sont en guerre pour quelques arpens de neige vers le Canada."

Introduction

With these words, Candide's travelling companion Martin, apparently a Socinian, explains the madness of the English and French. And he adds, "qu'elles dépensent pour cette guerre beaucoup plus que tout le Canada ne vaut". This is not the only allusion to the Seven Years' War to be found in Voltaire's 1759 masterpiece Can-dide or Optimism. It is one of many examples that show how attentively Voltaire, probably the best-known representative of the French Enlightenment at the time, followed and commented on world events. Voltaire was one of the first to epitomise the type of committed intellectual so characteristic of the 20th and 21st centuries, who critically observed and commented on current events and passionately advocated his concerns. And like many intellectuals of the 20th century and the present day, he also sought the proximity of the powerful and the powerful sought his proximity.

Voltaire accompanied the Seven Years' War with critical remarks from the very beginning and it occupies a large space as a reference in his late work. In my contribution, I examine Voltaire's view of the Seven Years' War - i.e. comments, explanations, judgements - in its various forms of expression: firstly as commentary in his daily correspondence, secondly in literary, thirdly in philosophical and fourthly in historical analysis: in Candide, in the Dictionnaire Philosophique and in Précis du Siècle de Louis XIV. How did he assess the epochal changes in European alliance politics that preceded the war? Did he recognise the global dimension of the conflict? How did he react to news from the theatre of war, what tone did he adopt towards his correspondence partners? This is just a selection of the questions that arise.

Voltaire as an observer of the course of the world

The looming world conflict was brought up by Voltaire at an early stage. In his famous letter to Rousseau dated 30 August 1755. In his famous letter of 30 August 1755 to Rousseau on the occasion of the publication of the Discours sur les fondements de l'inégalité parmi les hommes, Voltaire referred to the skirmishes in North America: "Je ne peux non plus m'embarquer pour aller trouver les sauvages du Canada, [...] parce que la guerre est portée dans ce pays-là, et que les exemples de nos nations ont rendu les sauvages presque aussi méchants que nous".

Despite the sharp irony of the remark, which is directed against the idea of the bon sauvage and also reflects reports of the Indians' cruel war rituals, it should not be overlooked that Voltaire had already grasped key aspects of the conflict in America: on the one hand, the fact that the Indians were players in the struggle between France and England for the vastness of America, and on the other, that it was a conflict between two European, "civilised" powers that was being fought outside Europe. Voltaire wrote this two months before the first "real" battle in North America, Braddock's defeat at Monongahela on 9 July 1755.

From then on, the conflict was a recurring theme in Voltaire's letters. Voltaire was well aware of the balance of power in America during the first years of the war. At the beginning of February 1756, he wrote to the Duchess of Saxe-Gotha that the English were in trouble in America and the French at sea.

From February 1756, Voltaire combined his commentaries on the "politics of the day" with criticism of the philosophical optimism of the "best of all possible worlds", which had characterised his writings since the Lisbon earthquake and was to be intensified once again in Candide. His correspondence reads like preliminary exercises for his most famous work. Voltaire remarks to his friend Argental, "Le tout est bien me paraît ridicule, quand le mal est sur terre et sur mer", and to Elie Bertrand, "Le mal est sur la terre, et c'est se moquer de moi que de dire que mille infortunés composent le bonheur". The war for Canada is not compatible with the tout est bien, let alone with the idea that men and peoples would make reason the basis of their actions. Voltaire wrote to Thieriot at the end of February 1756: "Le tableau de sottises du genre humain depuis Charlemagne jusqu'à nos jours est ce qui m'occupe [...]. I do not know that there are in this tableau many traits more honourable for humanity than to see two nations in the ice and snow in America".

It is therefore not surprising that the outbreak of war in September 1756 also provoked sharp comments questioning the goodness of the world: "Tout est bien, tout est mieux que jamais. Voilà deux ou trois cent mille animaux à deux pieds qui vont s'égorger pour cinq sous par jour. [...] The best of the moons is horribly ridiculous. Il faudrait voir tout avec des yeux stoïques," he wrote in a letter to F. L. Allamand on 17 September.

His commentary on Frederick II's invasion of Saxony also shows that Voltaire recognised the power-political dimensions involved: "Vous devez savoir à present vous autres Parisiens que le Salomon du Nord s'est emparé de Leipsik. Je ne sais si c'est là un chapitre de Machiavel ou de l'Antimachiavel, si c'est d'accord avec la cour de Dresde ou malgré elle. [...] I promote in the allées de fleurs de mon invention, et je prends peu d'intérêt aux affaires des Vandales et des Misniens".

However, it is not true that Voltaire did not concern himself with the affairs of the "Vandals" and "Meissner" (the Saxons): from 1755 onwards, he repeatedly addressed current political events in his correspondence, be it the Westminster Convention, the still undeclared war between England and France or the Franco-Austrian alliance. Even as the war progressed, Voltaire was not to be the hermit or "groundhog" in Switzerland, untouched by events. Voltaire also tried his hand as a diplomat on several occasions, offering himself to the government in Versailles and to Frederick the Great as a mediator or "post box" for secret negotiations.

Like many of his contemporaries, Voltaire was surprised by the renversement des alliances - it had been unthinkable for him too. There was no doubt in his mind about the scope and consequences of this reorganisation of the international system: "Cette guerre n'a pas mine de finir si tôt. Would you ever have thought that France, France and Russia would fight against one prince of the empire! Only God knows what is to come; the comte d'Estrées and the intendant of the French army must already be in Vienna. [...] Mr de Broglie and Mr de Valori are said to have returned to Paris, and that four to fifty thousand ambassadors will take their place. And it is a crossroads between Canada and the whole of Europe. Ah, que ce meilleur des mondes est aussi le plus fou!", he wrote to the Duchess of Saxe-Gotha in November 1756.

In September 1759, after the publication of Candide, Voltaire wrote to his publisher Cramer: "Si Candide a été en Saxe, il doit douter plus que jamais du sistème du docteur Pangloss. Tout ce qu'on apprend de ce malheureux pays tire des larmes". Reality - in this case the example of the Electorate of Saxony, which had been systematically plundered by Prussia since 1756 - provided Voltaire with irrefutable arguments against the idea of the "best of all worlds" and the principle of "all is well".

Voltaire did not lose this eye for the reality of war throughout the entire war; his correspondence repeatedly contains remarks such as this, in a letter to the Duchess of Saxe-Gotha, whose territory was directly affected by the war and its accompanying symptoms: "Je vois les malheurs du genre humain augmenter sans qu'ils produisent le bien de personne".

Although he himself had once written a panegyric on Louis XV's victory at Fontenoy (1745), Voltaire knew only too well what lay behind the reports of battle victories. His commentary on the Battle of Lobositz, the first of the many bloody battles of the Seven Years' War, already refers to the third chapter of Candide, which I will come to later: "Voilà déjà environ vingt mille hommes morts pour cette querelle, dans laquelle aucun d'eux n'avait la moindre part. It's still one of the best possible tributes of the world. Quelles misères! et quelles horreurs!" (to the Duchess of Saxe-Gotha).

Thanks to contacts in the Empire and with the Duchess, Voltaire was well supplied with news on the progress of the war. Voltaire repeatedly expressed his concern that the small duchy could also become a theatre of war. A small masterpiece of irony and humour is Voltaire's New Year's greeting to the Duchess in 1758, which he prefaces with a tirade against the "Croats, Pandurs and Hussars" who might intercept the letter, and in which he opposes them, who seek to "make the world the most horrible of all worlds", with the Duchess as a model of spirit and courtesy.

As we have already seen, the epoch-making event that preceded the outbreak of war in Europe was the Renversement des alliances. Secret negotiations between Versailles and Vienna had been underway since September 1755, which were given new impetus by the Westminster Coalition and finally resulted in the first Treaty of Versailles on 1 May 1756. While the Westminster Convention could be interpreted as a solo effort typical of Frederick II, the Franco-Austrian Treaty was a sensation that shook the whole of Europe.

Voltaire reacted calmly to the British-Prussian alliance. The Prussian king wrote verses and signed treaties, and he could certainly see the good side of the treaty because, according to Voltaire in a letter to the Duchess of Saxe-Gotha, it would prevent the colonial conflict from spreading to Germany (which was certainly one of the British's aims).

Voltaire was all the more surprised when he learnt of the Treaty of Versailles. "Il ne faut que vivre pour voire des choses nouvelles", he wrote in a letter to Countess Lützelburg, and remarked to Jean-Robert Tronchin that Charles V could not have imagined this. For the historian Voltaire, there was no question that the new alliance was a special event.

He wrote to his former protector and current business partner, the financier Joseph Pâris-Duverney, who was close to the court and in particular to the Marquise de Pompadour, about the possible consequences: "Les événements présents fourniront probablement une ample matière aux historiens. The union of the French and French armies after two centenary years of imitation, Angleterre, which managed to tip the balance of Europe in six months, a formidable navy created with rapidity, the greatest fermeté deployed with the greatest modération: all this forms a magnificent tableau. The foreigners admiringly saw a vigour and an esprit de suite in the ministry that their prejudices did not want to believe".

It is not certain whether Voltaire's laudatory remarks about the effect of the Franco-Austrian alliance were not also aimed at Madame de Pompadour and Louis XV via Pâris-Duverney, in the hope of regaining their favour and possibly returning to Paris. He precisely grasped the ideas underlying the alliance on the part of France, if one includes a letter that he addressed to his "friend", the Duke of Richelieu, in October. England was to lose its most important partner on the continent, which would go hand in hand with the neutralisation of the Austrian Netherlands, the classic battleground between the three powers. This meant that the British lacked the classic bridgehead to Europe. They had to fall back on the East Frisian harbours during the war and posed no threat to French territory with their troops.

Voltaire was not unaware of the side effect of the alliance between Versailles and Vienna, namely the control of the turbulent Savoy-Sardinia. In the spring and summer of 1756, France could therefore look to the future with optimism, having achieved a victory in the Mediterranean over the seemingly overpowering Royal Navy with the conquest of Menorca.

Voltaire's initial approval of the new alliance gradually gave way to increasing scepticism. While in the spring of 1757 he still spoke of the great honour France would gain from being Austria's sole support, in October he saw the danger that the destruction and division of Prussia would give Austria greater power than it had ever possessed under Ferdinand II. Prussia would undoubtedly have to surrender Silesia, but why destroy it completely - as envisaged in the Second Treaty of Versailles? Preventing this was the task of Louis XV, who would thus be a true "arbitre des puissances". His reflections show Voltaire to be in agreement with the majority of the politically-minded public, who had great difficulty getting used to the fact that Versailles and Vienna were now allies.

Like the majority of the French, Voltaire regarded the defeat at Rossbach as a humiliation and quite rightly saw it as a turning point in the war, as there could no longer be any talk of a quick victory over Frederick the Great. What was foreshadowed at Rossbach was finally confirmed by the Prussian victory at Leuthen. There was no longer any hope of a quick peace, and England also cancelled the Convention of Zeven Abbey, which prompted Voltaire to remark that international law was nothing more than a chimera and that from now on the law of the strongest would apply. According to Voltaire, the "système de l'Europe" was on the brink of fundamental change. His despair about the expected bloodshed was already spreading in January 1757: "Le sang va couler à plus grands flots dans l'Allemagne, et il y a grande apparence que toute l'Europe sera en guerre avant la fin de l'année. Cinq or six cents of people will be there. The rest will be left behind.

Voltaire saw the conclusion of a new Peace of Westphalia as the only way out of the impasse.

The subject of Voltaire's letters was of course always Frederick the Great, with whom he himself was in irregular contact until 1760. Although Voltaire still resented the Prussian king for the humiliation he suffered in Frankfurt in 1753, as he repeatedly emphasised to third parties, there is not much evidence of this in the correspondence of the first years of the war. The two exchanged pleasantries, philosophised about suicide, which Frederick was considering and which Voltaire forbade, and commented on the course of events in verse. The death of Friedrich's sister Wilhelmine, who acted as a "postbox" or "postwoman", was a turning point for both of them. Communication now became more irregular and difficult, and numerous letters were lost.

The attempt made by Voltaire between 1759 and 1760 to act as a mediator between Frederick and Choiseul was doomed to failure from the outset. Neither side was prepared to compromise at this time (especially after Frederick's defeat on 12 August 1759 in Kunersdorf). Choiseul did not regard this dialogue via detours as official negotiations, but as a conversation between friends. Furthermore, he was neither prepared nor authorised by Louis XV to risk the Austrian alliance. Frederick also rejected any peace that would not bring him glory.

While their correspondence was characterised by a tone of mutual respect until they fell silent, Voltaire did not hold back in his harsh judgements of the Prussian king's behaviour towards others, although these were always mixed with admiration and astonishment at his survival skills. The consistent plundering of Saxony by Prussia prompted Voltaire to equate Frederick with the bandit captain Mandrin, who had devastated Savoy and the Dauphiné with an entire army of robbers a few years earlier. In the same letter, Voltaire reports that the agnostic Frederick did not shy away from showing himself to the cheering Dresden population with two "fat" Lutheran pastors. Reading this passage, one gets the impression that Voltaire grudgingly admired this cynicism on the part of the Prussian king, who was quite successful in instrumentalising the latent confessional tension in the empire to mobilise his supporters.

Frederick, the "Margrave of Brandenburg", against whom the whole of Europe had united, would only achieve dubious fame in his hopeless defence against the greatest powers in Europe, judged Voltaire in the summer of 1757, before the war was turned by Rossbach and Leuthen. After Rossbach, Voltaire had to grudgingly congratulate the "Margrave of Brandenburg" on his victory, but his fame, Voltaire admitted in December 1757, was based on blood.

Voltaire was repeatedly astonished by the Prussian stamina. He explained this - not without good reason - with the quality of the army and the solidity of the finances. Nevertheless, Prussia's survival was nothing short of a miracle, given the overwhelming superiority of its opponents and their equal fighting power. Rossbach became a metaphor for these military miracles. In October 1759, he wrote to Tronchin about Frederick's confrontation with the Russian army: "Quoyque Luc ait frotté quelques croates il ne peut se tirer d'affaire que par des miracles, par quelque Rosbac. Mais on ne rosbacque point les Russes. Ces gens là se croiroient damnez s'il reculaient. They are fighting by deception".

Voltaire saw something positive in the fact that Frederick the Great and Prussia were still able to assert themselves in the end, as this also preserved a bastion against infamy in Germany: "Pour Luc quoy que je doive être très fâché contre luy, je vous avoue qu'en qualité d'être pensant, et de français je suis fort aise qu'une très dévote maison n'ait pas englouti l'Allemagne et que les jésuittes ne confessent pas à Berlin. L'infâme est bien puissante vers le Danube", he wrote to d'Alembert in November 1762.

Candide and the Seven Years' War

During the seven years of war, Voltaire developed great creative energy: Candide, the conte philosophique, probably his most famous and best-known work, was published in January 1759 and became a great success, not only in Paris but also in Germany, as reading material for the officers taking part in the almost endless military campaigns. Voltaire also found a new task that was to characterise his writings from then on: the fight against "l'Infâme", that complex of superstition and fanaticism that is still such a dangerous mixture today.

Allusions to the Seven Years' War run like a red thread through the novel. This begins with the title. Voltaire published the novel anonymously; the author is named on the title page as a docteur Ralph, in whose pocket the manuscript was found - when he died in Minden in 1759. This addition is not found on the first editions, from January 1759, but was added in 1761: Perhaps to ensure credibility - after all, Minden borders on Westphalia, Candide's homeland - but above all in allusion to the Battle of Minden, in which the French advance on Hanover was repulsed on 1 August 1759.

Two years before the end of the war, every reader in Europe knew the significance of this battle of the Seven Years' War, which is mostly overlooked today: it was here that the attempt to conquer the Electorate of Hanover failed, thus gaining a bargaining chip that could be used in negotiations against losses overseas. Fittingly, Voltaire included a very long chapter on Candide's stay in Paris, which contains a sharp criticism of the state of French society.

The novel tells of the picaresque odyssey of the naive Candide, who is cast out of the Westphalian castle of Thunder-ten-Tronck: In the second chapter, Can-

dide recruiters of the King of Bulgaria, in chapter three we witness a bloody battle. Voltaire describes the contemporary recruitment practices and the inhuman discipline established by force in the Bulgarian, i.e. Prussian, army. The Bulgarian king - none other than Frederick the Great - saves Candide, a victim of the gauntlet, from certain death because he recognises in him the "young metaphysician" who knows nothing of the things of the world.

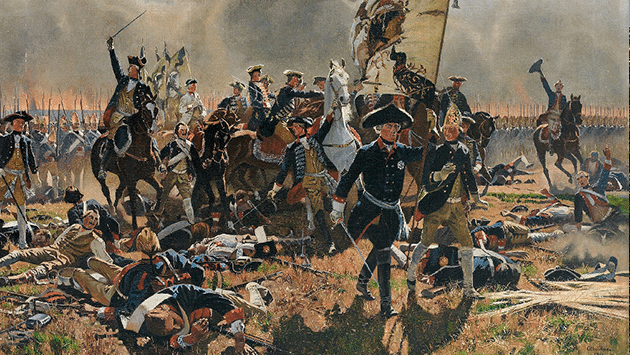

Candide soon learns what is happening in the world when the battle between the Bulgarians (Prussians) and the Abars (Austrians) takes place. Voltaire describes this battle, and thus the war, with a vividness rarely seen before (perhaps apart from Grimmelshausen's Simplicissimus). A battle is nothing other than a "boucherie héroïque", in which thousands of "coquins" are transported from the best of all worlds in the blink of an eye, and in which villages and their inhabitants are invaded and massacred according to the rules of public law (i.e. international law). The whole thing is sanctioned by the church, which celebrates these heroic deeds with a Te deum.

But it's not just the Bulgarians and Abars who have strange war customs, the English do too: "Mais dans ce pays-ci il est bon de tuer de temps en temps un amiral pour encourager les autres."

The indictment of war

The last years of the war saw the beginning of the Calas affair and the editing of the Dictionnaire philosophique, the pamphlet against the infamous.

The unfortunate connection between the church and warfare also occupies a large place in the article Guerre in the philosophical dictionary. The commanders and soldiers invoke God before they massacre their opponents or are massacred by them. If the battle and the number of casualties were high enough, a Te Deum was sung in the churches and clergymen of all denominations praised the victories in long speeches in which a battle in the Wetterau region of Hesse - an allusion to operations by the French army in the Seven Years' War - was compared to biblical battles.

The article Guerre primarily criticises the typical cause of war in the Ancien Régime: the succession conflict, which was not the trigger for the Seven Years' War. This is one of the things that makes the Seven Years' War so special and heralded a new era in international relations. Did Voltaire regard the causes of the Seven Years' War - the colonial conflict - as a special case that should not be taken into account? Be that as it may, in this article - and this is more relevant than ever since 24 February 2022 - Voltaire relentlessly denounces the senseless deaths of people in wars.

Wars that are triggered by a few people for trivial reasons - dynastic conflicts and the coalition-building that goes with them. But Voltaire was under no illusions: although humans are characterised by their rationality compared to animals, war remains one of the three great scourges of humanity alongside hunger and the plague, but unlike the first two, it is man-made. Voltaire is aware of man's violent nature and realises that there will always be wars. His unspoken appeal here is aimed at, if war cannot be abolished, at least waging as few wars as possible. The fight against the infamy that contributes to the cruelty of war is therefore also a fight for a more peaceful world.

Voltaire as a "contemporary historian"

Voltaire's philosophical-pacifist commentary on the Seven Years' War must be complemented by his historical-political commentary. As one of the leading historians of his time - he published Siècle de Louis XIV in 1751 and Essai sur les mœurs in 1756 - Voltaire not only possessed the necessary judgement to assess the events of the years 1755 to 1763, he also had contacts with those directly and indirectly involved in decision-making processes thanks to his acquaintance with members of the government and the diplomatic corps. These included Marshal Richelieu, conqueror of Menorca (1756) and commander-in-chief of a French army in Germany in 1757-1758, the Abbé de Bernis, who negotiated the first Treaty of Versailles on behalf of the king and was appointed first Minister of State and then Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs in 1757, his successor Étienne-François Count of Stainville, Duke of Choiseul since 1758, and César-Gabriel Count of Choiseul, Duke of Praslin in 1762. Voltaire was only in contact with Stainville-Choiseul through letters; they never met. However, he had known the later Duke of Praslin (Count of Choiseul) and Abbé Bernis personally since the 1740s. But despite these contacts and despite the fact that Voltaire temporarily served as a mailbox for unofficial communication between Frederick and Versailles, he did not gain any closer insight into the decision-making processes within the French government. Voltaire's attempts to intervene as a player in the diplomatic game cannot be discussed in detail here, as they were all unsuccessful.

Just five years after the end of the war, Voltaire published a history of the Seven Years' War as part of the Précis du siècle de Louis XV. Starting with the earthquake in Lisbon, which in retrospect foreshadowed the Seven Years' War, he emphasised the uniqueness of the war. It was distinguished from all previous wars by the "revolutions" that preceded it, meaning the shifts in traditional alliance systems, by its expansion to all continents of the world, and not least by the survival of Frederick the Great, who had to fight against a seemingly overpowering coalition - and escaped annihilation thanks to the discipline of his army and his superior generalship. For the historian and Enlightenment philosopher Voltaire, there was no "miracle of the House of Brandenburg", even in politics, and Prussia's survival can ultimately be explained rationally.

Voltaire grasped the global political context of the war very precisely: the dispute between England and France over the wilderness of America had triggered the aforementioned revolutions in the European alliance landscape, creating a smouldering fire that a few sparks could set alight. These came from overseas on the one hand, and from Frederick's invasion of Silesia on the other.

The historical dimension of the alliance between the Bourbons and the Habsburgs is explicitly recognised, but Voltaire's explanation falls short of the considerations he made in the aforementioned letters to Pâris-Duverney and Richelieu. The ironic and sarcastic punch line - "Ce que n'avaient pu tant de traités de paix, tant de mariages, un mécontentement reçu d'un électeur, et l'animosité de quelques personnes alors toutes-puissantes que le roi de Prusse avait blessées par des plaisanteries, le fit en un moment" - blocks the view of the actual background to the renversement of the alliances, namely the desire of Louis XV. and also the English, not to allow the colonial conflict to spread to Europe. The provocations of Austria, which was seeking conflict with Prussia, and Frederick's unrest led to this terrible war, in which not only the Saxon ruling family but also, as Voltaire rightly mentioned, millions of other families had to endure the worst suffering.

Voltaire condenses the actual course of the war in Europe into a few paragraphs (consistently realising his maxim as a historian not to lose himself in endless descriptions of battles): Never had so many battles been fought with so little consequence, never had so much blood been spilt in vain, never had Germany been the main theatre of war and never had France been spared the horrors of war, but it had lost a lot of money. He contrasts the undecided struggle in Europe with the major changes in the colonies. Here, the loss of 1200 men could not easily be compensated for, and in a single battle - on the Abraham Fields off Quebec - 1500 miles of territory, two thirds of which was ice desert, had been lost.

If Voltaire largely ignores the content of the Peace of Hubertusburg and the confirmation of the status quo in Europe in 1748, he deals all the more thoroughly with the actual defeat of France, the loss of its colonial empire. England had achieved an unprecedented supremacy at sea, united the whole of North America under its rule (which Voltaire did not regard as too great a loss), expelled the French from India, taken over the French possessions in Africa apart from Gorée, and dominated trade in the Caribbean, where France was able to retain the "sugar islands", Martinique, Guadeloupe and St Domingo. A dishonourable and yet necessary peace that saved France from complete bankruptcy, Voltaire concluded.

Outlook

Voltaire's letters and writings offer a wide range of material for analysing the history of how his contemporaries perceived the war. His conception of history, which transcends Eurocentric perspectives, gives his political and historical reflections on the Seven Years' War a surprising "freshness". The Seven Years' War was not a purely European war and, as is well known, its outcome brought about the greatest changes outside Europe.

His comments and assessments of the changes in alliance policy in the run-up to the war are revealing and rarely considered in accounts of the history of the war. They point once again to the renversement des alliances, which was perceived as so revolutionary by contemporaries, and to the sensation caused by the news of the conclusion of the Franco-Austrian alliance. As we have seen, Voltaire remained rather sceptical in his assessment of the alliance for France.

Although he saw its consequences for the Italian peninsula, for example, which was to be spared war until the outbreak of the Revolutionary Wars (letter to Pâris-Duverney), he remained sceptical and to some extent still trapped in old enemy images as far as the effect of the alliance on Germany and the Old Empire was concerned. Here he feared Austrian supremacy along the lines of Ferdinand II during the Thirty Years' War and therefore warned against the complete destruction of Prussian power. For Voltaire, as for French diplomacy of the time, the Peace of Westphalia formed the basis for any reflection on Germany's political order. He would therefore have agreed with the restoration of the status quo in the empire on the basis of the Peace of Westphalia (Article XIX of the Peace of Hubertusburg), even if he made no statements on the political consequences of the Peace of Hubertusburg.

Voltaire's reconstruction of the genesis of the Franco-Austrian alliance reveals the limits of his knowledge. Only the Abbé Bernis, who tore down Richelieu's system and replaced it with a new, larger one, was responsible for this. Louis XV, along with Kaunitz the real "mastermind" in the realisation of the alliance, is not mentioned, but Voltaire cannot be blamed for this, because for a long time, even in more recent historical research, hardly any reference has been made to the king's contribution to the realisation of the Treaty of Versailles.

However, Voltaire's numerous remarks on war, which abstract from the circumstances and causes of the Seven Years' War, have lost none of their topicality. Voltaire was aware of man's tendency towards violence and war and he never ceased to point out the reality of war: death and misery. The civilised, comparatively chivalrous interaction between the Prussian and French officer corps and commanders during the war, shaped by the enlightened cosmopolitan ideals of the era, should not obscure this.

In battle, class boundaries disappeared, musket and cannonballs, bayonets and sabres did not care about patents of nobility. Voltaire counted the fact that succession disputes triggered wars in the Age of Enlightenment as one of the worst "follies of the human race". Viewed from this perspective, his letters, his Candide and the article "War" in the Dictionnaire philosophique contain timeless commentaries on the nature of war, which unfortunately have lost neither their urgency nor their topicality even in the 21st century.