The title of the evening is "What is language? With this question, it is important not to turn immediately to its subject - language - but first to clarify what kind of question is being asked here, if the question is to be a genuinely philosophical question.

This is because the philosophical question does not focus on language in the way that the individual sciences do in their way of asking questions: "What is magnetism?", "What is epilepsy?". Such questions ask about unknown facts in the world in order to familiarise and explain them. Of course, you can also ask about language in this way - but then language is not the subject of philosophy, but the subject of an individual science, such as linguistics or neuroscience.

In contrast to such questions, philosophy thematises what is always already presupposed in those questions. This not entirely straightforward idea can be explained by Kant by way of introduction in such a way that the empirical sciences ask about facts in the world, whereas the world as such becomes a problem for philosophy. However, this requires a fundamentally different form of questioning. For the world, which is presupposed in every empirical experience as an encompassing horizon, cannot itself be an empirical experience as the epitome of what can be experienced empirically. The world does not exist in the world, so to speak, without therefore being a figment of the imagination.

Philosophy therefore does not ask about something that exists independently of the question, but about something that is always already implied in the question as such in an unclear way. In other words, a peculiar self-referentiality is essential to the thinking and language of philosophy, which is always already obscurely presupposed in thinking and language and which philosophy aims to elucidate.

Thinking and speaking

Thinking and speaking are related, but not identical. The relationship is expressed in the peculiar self-referentiality that thinking and speaking are capable of. We can think and talk about anything: the weather, our last holiday or magnetism. But we can also talk about language, think about thinking.

The non-identity of thinking and speaking, on the other hand, can be traced if one ponders the question of whether thinking or language is the more fundamental and significant manifestation of self-reference. The philosophical tradition is characterised by the fact that it considers thought to be more fundamental and significant, while language is rarely and almost reluctantly addressed - for example, as a more or less suitable instrument for expressing thought.

Rosenzweig's thinking along the lines of language, in critical opposition to this philosophical tradition, aims to make it clear that although thinking is fundamental, the language that arises from the basis of thinking and its logic is more important than the ground on which it rests.

Rosenzweig's project can be illustrated in advance with the help of a parable. It is obviously true that the foundation for a house is fundamental in the literal sense: the house rests on it and thus gains its stability. However, it would obviously be wrong to conclude from the fundamental character of the foundation that man must consequently live in the foundation. Rather, it is more reasonable for people to live in those storeys of the house that are established and made possible by the foundation, but which are not identical with the foundation, but essentially go beyond it, as they rise above it.

Rosenzweig's thinking about language therefore starts with thinking as a foundation, in order to then go beyond this foundation to language in a decisive step. For although thinking is the foundation of human existence, language is what makes this existence meaningful and worth living by elevating itself and the human being above pure thinking.

Thinking and universality

Thinking has always fascinated and captivated philosophy because it has an intimate relationship with totality. Being and thinking are one, according to Parmenides, because both being and thinking are universal and comprehensive. What is not is nothing; and what cannot be thought is unthinkable.

Rosenzweig certainly recognises the fundamental character of this consideration; however, he points out that the fundamental, precisely because it is the fundamental, is not everything, because the more important, the more significant, only rises from the ground and goes beyond it, i.e. differs from it and emancipates itself.

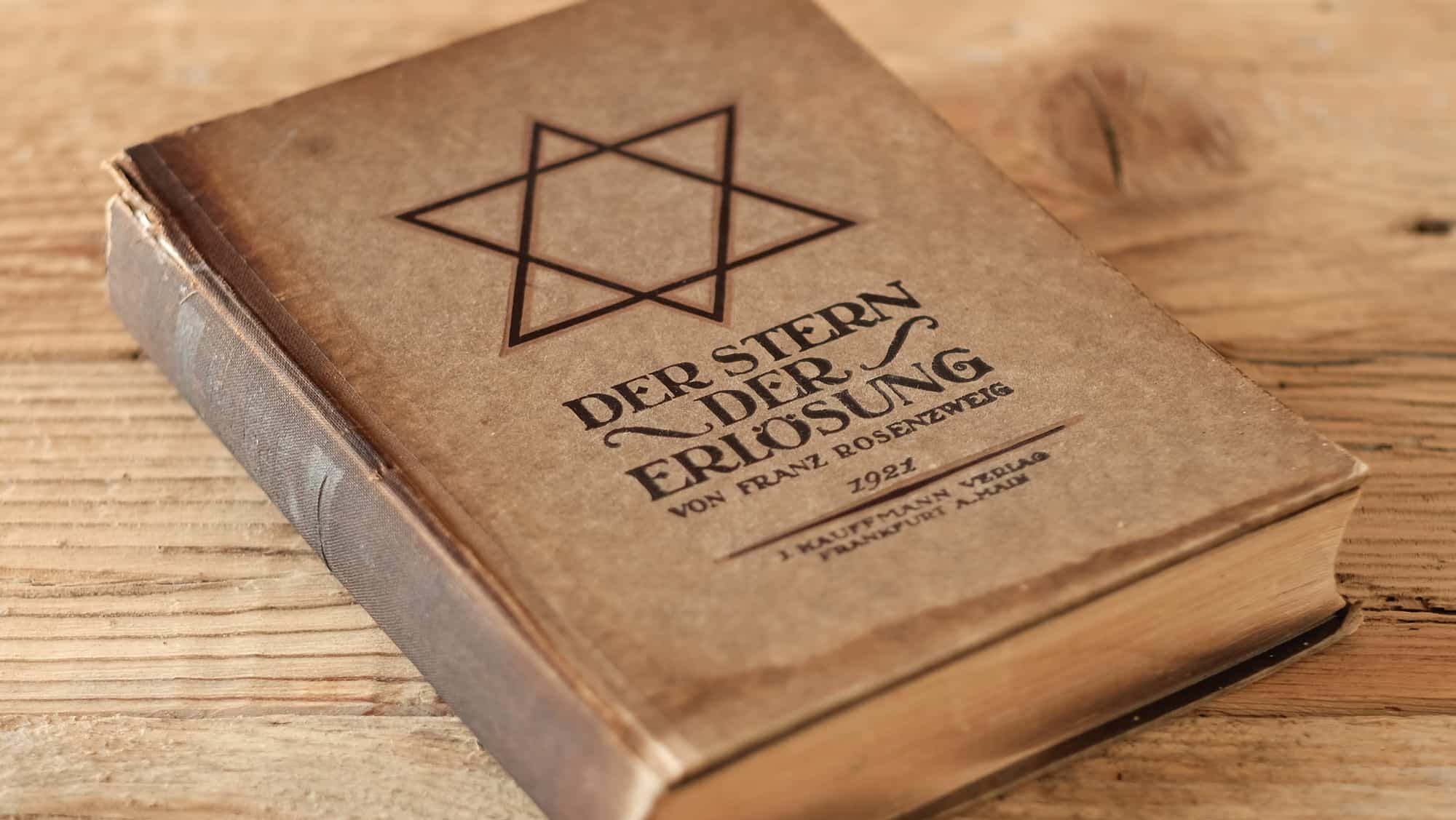

Rosenzweig says this at the beginning of The Star of Redemption:

The first sentence of philosophy, "Everything is water", already contains the precondition for the conceivability of the world ... For it is not a matter of course that one can ask "what is everything?" with the prospect of a clear answer. One cannot ask: "what is much?"; only ambiguous answers could be expected; on the other hand, the subject everything is already assured of an unambiguous predicate. The unity of thought is thus denied by those who, as happens here, deny the omnipotence of being. He who does so throws down the gauntlet to the whole venerable society of philosophers from Jonien to Jena. (Stern, p. 13)

With these sentences, Rosenzweig defines the starting point of his book very succinctly. Thinking believes that it can be absolutely certain of its supremacy, which the philosophical tradition repeatedly ascribes to it, because reality - according to the implicit premise - forms an ultimately homogeneous allness, which can therefore be adequately grasped in thinking and only in thinking through its guiding question of what everything is.

But what becomes of the unity of being and thinking celebrated from Jonien to Jena if the premise is false; if reality is not a homogeneous allness but a heterogeneous multiplicity? What are the consequences if not everything that is real can be lumped together in the one comb of one being and thinking, because a concrete reality refuses to merge into this all and disappear?

But what kind of strange disturbance would that be that resists being absorbed by the universe? What does not fit into the totality of being and thinking? Or better and more precisely: who resists, who says "No!" to integration into the big picture?

Rosenzweig's answer is: it is we humans, not in the purity of our thinking, but in the concrete details of our lives and actions. We ourselves as concrete individuals are therefore the troublemakers of traditional philosophy.

In this sense, it will be shown how Rosenzweig takes the side of us troublemakers in order to show critically against the philosophy of tradition that we can only understand ourselves adequately if we understand ourselves from language, which arises from the ground of thinking but is not identical with it, because language is freer, more significant and more concrete than pure thinking.

I-say

The concrete, individual person manifests his or her idiosyncrasy by saying "I". In the context of the considerations made here, it is important to be aware of the difference between saying "I" and thinking "I".

The "I think", which according to Kant must be able to accompany all my ideas, is general and all-encompassing. The self-referentiality of thought here takes on the more specific form of a consciousness of itself. This pure self-consciousness in "I think" is strictly identical in every human being and in this way makes the universality of the logical possible. Ego-thinking is, as Kant says very vividly, the highest point to which thinking and its logic must be attached, as it were, in order to explain and secure its generality.

By saying "I" (and not just thinking it), a person rises above the basis of general self-consciousness. He embarks on the adventure of his own self-realisation and self-knowledge, which is made possible by the generality of ego-thinking, but is by no means exhausted. In the transition from thinking to speaking, the human ego thus gains its first concrete reality.

Rosenzweig says this in the centre of the Star of Redemption:

I" is always a loud "no." "I" always sets up a contrast, it is always underlined, always emphasised; it is always an "I but".

In the I-saying, the concrete I rises above its general self-awareness by beginning to recognise itself as "this way and no other". Of course, this is only the beginning of self-recognition. For this beginning, as Rosenzweig continues, immediately raises a new question:

The "not different" is immediately countered by the question: "not different from what?" It [the ego] must answer: "not different from everything". For something that is described as "like this and nothing else" is to be differentiated from "everything". And it is "not different" from everything. It is already set as different from everything by the so; the "and not different" that is added to the so means precisely that, although different, it is nevertheless also not different from everything, namely capable of being related to everything. (Stern, p. 193f.)

This very condensed passage describes a profound conception of the human ego gained from the guiding principle of language. It is therefore worth unfolding the condensed formulation step by step.

The "no" that becomes loud in the concrete "I" is directed against the ontological appropriation of the "I" by the universality of being and thinking. The human ego awakening to self-knowledge realises its uniqueness as a task and obligation. It is precisely at this moment, however, that language gains a new meaning for the awakened ego, a new vitality that is alien to the pure thinking that forms the basis of the new way of speaking.

This relationship between reason and living existence, which now emerges more clearly, forms the systematic centre of Rosenzweig's linguistic thinking. It should therefore be emphasised once again that the upgrading of the I-saying as opposed to the I-thinking does not mean that thinking and its logic are simply abandoned or skipped over. We do not speak, i.e. we do not speak intelligibly, if we speak illogically; but the correct adherence to logic does not exhaust the meaning of a living speech that rises above its logical basis.

However, as Rosenzweig makes clear, the new dimension of the "I-saying" gained through the initial "no" against the homogeneous universe does not stop at the mere "no". The I-saying only gains its actual reality in a new "yes", which is made possible by the initial "no". The ego that has awakened and isolated itself in the "no" can enter into a lively and meaningful relationship with other individuals, which would not be possible in this form within the homogeneous universe. Only those who can say "no" can also say "yes" in a meaningful, valuable sense.

Rosenzweig is primarily thinking here of the primal phenomenon of conversation as the guiding principle of language. Only "I-sayers" can have a genuine, lively conversation with each other, because the pure "I think" is, strictly speaking, monologue. In thinking, the silent self consults with itself, so that language appears to it as a mere aid and instrument with which what is thought in solitude can be communicated from time to time. However, this reference to communication and language remains external to pure thinking, so that the concrete and living ability to relate, which Rosenzweig's language thinking places at the centre of his considerations, is also alien to it.

The awakening of the ego thus goes hand in hand with the discovery of a language that can no longer be instrumentally understood as a mere tool of thought. I think monologically about something; in contrast, I speak with a person, i.e. a concrete you, who is more and different than an object of pure thought. In the silent relationship of the thinking I to the It of its object, the monological I has priority; in the genuinely dialogical relationship of the speaking I to a You, on the other hand, the You has priority. I am I because I was and am addressed by the You. That is why a genuine dialogue can give me an insight that I cannot think up silently and for myself alone. As long as I am only talking about something, I am not yet having a conversation and language remains a tool; only when I talk to someone does language come to life.

Rosenzweig's "language thinking" thus places two facts at the centre that traditional philosophy considers unimportant: the fact that we need an interlocutor in order to speak (and thus also for lively thinking); and - as will now be shown - that we need time in order to speak (and thus also for lively thinking).

Time and sense

As has been shown, Rosenzweig's language thinking is orientated towards the primal phenomenon of language, which goes beyond pure thinking as its foundation. At the same time, language thinking is also a thinking, a new thinking, as Rosenzweig says. In his important essay entitled "The New Thinking", he states:

The method of thinking, as developed by all earlier philosophy, is replaced by the method of speaking. Thinking is timeless, it wants to be; it wants to make a thousand connections at a stroke; the last, the goal is the first for it. Speech is time-bound, time-nourished; it cannot and will not leave its breeding ground; it does not know in advance where it will emerge; it takes its cues from others. (The new thinking, p. 151)

Once again, thinking, or more precisely, the old thinking of tradition, forms the starting point. This thinking is timeless and wants to be. In fact, it is the questionable pride of traditional thinking to be able to make "timeless" statements. The judgement "A = A" is not only true today, but always true.

This seems to be different with an empirical statement such as "This tree has green leaves". But appearances are deceptive. You only have to complete the judgement by specifying the exact time: This tree has green leaves at this exact point in time. The judgement completed in this way, if it is true, is always true.

Remarkably, these "timeless" truths often have to be formulated in the past tense: "This tree had green leaves on 23 April 2020 at 10 a.m.". The supposed "timelessness" of pure thinking therefore resembles the immutability of the past. This is why pure thinking does not recognise a living present and future.

It is therefore a self-misunderstanding of thinking to interpret its independence from a specific point in time as nontemporality, even as eternity. For thinking here only imitates the peculiar property of time itself to remain unchanged as time despite all the changes that occur in time. Everything changes in time, but time itself always remains the same and thus always continues. Rosenzweig therefore calls the supposedly timeless validity of thought more accurately and correctly its perpetual validity. Even and especially where it makes true, perpetual judgements, thinking remains bound to that linear time in which many things change, but which itself remains unchanged, i.e. always remains the same.

The original "no" of the ego, its ontological rebellion against the universe, is therefore also and above all directed against this monotonous always. For every point in time within linear time is identical to every other, the seconds pass uniformly and make everything in linear time indifferent. Likewise, every true judgement is identical with every other true judgement in terms of its truth value. Every true thought, according to Frege, means strictly the same thing, namely always the true. There is no more radical way to express the uniformity of pure thought and the indifference of its judgements.

The ego rebels against this uniform indifference by insisting on its concrete uniqueness, i.e. its irreplaceability. Furthermore, it wants to be in a living relationship with something equally irreplaceable - which is what makes the relationship valuable and meaningful in the first place. In the transition from general self-consciousness to concrete self-knowledge, the ego therefore not only demands a new way of thinking, but also a new time that does not make everything indifferent, but rather makes value and uniqueness possible.

Timelessness in the sense of the indifferent always means meaninglessness. Meaning only arises where something concrete really happens, i.e. has a real beginning and a real end - like every meaningful sentence in language. However, everything that has a real end is genuinely transient. It is this transience that gives the new time of the linguistic ego its peculiar dimension of meaning. For only a transient existence gains its unique dignity, its unmistakable value by virtue of its transience, in which we take a lively interest, precisely because what exists so concretely is fragile and not eternal. In this way, according to Rosenzweig, "time becomes completely real. It is not in it that what happens happens, but it, it itself, happens" (Neues Denken, p. 148).

Conclusion

The Star of Redemption is divided into three parts. The first part discusses the "Everlasting Foreworld", the second part the "All-Time Renewed World" and the third part the "Eternal Overworld". The first part is fundamental to the two following parts and for this very reason it is the least important part. For that which really has value and meaning rises above its perpetual ground, which monological thinking thinks, into the freedom of dialogical language.

The eternal pre-world is essentially mute, so that it can be represented and recognised most precisely in the only non-actual linguistic signs and formulas of logic and mathematics. The world of actual language, of actual understanding, rises from this ground: the history of the human ego and human freedom.

The eternally underlying pre-world can be explained, the present of our historical world, in which concrete things happen, can only be described - and only in language. Or to put it more precisely and better: Our historical present, in which we live as concrete selves in unmistakable relationships, can not only be described in language, but it can also be described essentially as language; as the language of meaning and understanding, as the language of personal relationships, as the language of dialogue.

The building that Rosenzweig erects on the mute ground of the eternal pre-world using language as a guide is therefore not a building in space, but a building in lived history, in which the concrete really happens because it has a real beginning and a real end. Thus, for Rosenzweig, living, meaningful language also has a real beginning, at which it rises from the perpetual muteness of the pre-world and the ego awakens to self-knowledge. For Rosenzweig, however, language also comes to a real end. This leads to the conclusion of the third part of the star, the eternal overworld, which is a supra-linguistic world because it is the future world of perfect understanding.

Wittgenstein ends his "Tractatus", which was published at exactly the same time as Stern 100 years ago, with the sentence: "Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent." Rosenzweig writes very similarly and yet quite differently in the final section of Stern:

What can be looked at is lifted above language, beyond it. The light does not speak, it shines. ... [It shines] like a face, like an eye shines, which becomes eloquent without the lips having to open. Here is a silence which, unlike the muteness of the previous world, does not yet have words, but which no longer needs words. It is the silence of perfect understanding. (Stern, p. 328)