Ja, just run after happiness / but don't run too hard! / Because everyone is running after happiness / Happiness is running behind", Bertolt Brecht summarises his Berlin experiences in the Ballad of the inadequacy of human planningwhich began in 1928 with the songs of the Threepenny Opera will be premiered. The religious sceptic sounds almost like a spiritual classic when, like the Doctor of the Church Augustine, he reflects on this: The pursuit of happiness and the search for peace of mind form a central theme of metropolitan existence.

This motif can also be found in the very "Berlinish" coloured poem Sunday morning by Mascha Kaléko:

The streets yawn tiredly and sleepily.

The factory rests silently like a museum.

A Schupo dreams of a paragraph.

And someone somewhere is making music.

The tram runs as if it were doing it for fun,

And you fly out, embellished by travelling clothes.

You act as if you still have to catch the train.

Today you don't have to. - But you're used to it.

The windows of the shops are locked

And sleep like human eyes. -

The Sunday clothes smell freshly ironed.

The smell of Brussels sprouts pervades the house.

One reads the well-heeled morning newspaper

And what the sale will bring from tomorrow.

The clock ticks quietly. - The water pipe roars,

To which a girl sings shrilly about love.

You sit on the balcony, surrounded by light.

A gramophone croons a tango far away ...

You get your first freckles

And feels good. - This is the day of the Lord!

Sunday morning was founded in May 1930 in the Vossische Zeitung was published. This was the first time that a Berlin office worker with Jewish-Polish roots spoke out publicly. Mascha Kaléko, née Engel, worked in the Berlin office from 1924. Workers' Welfare Office of the Jewish Organisations of Germany in Berlin Mitte: where today, in the vicinity of the Ora-

nienburger Straße, Jewish life has settled here again.

"I am employed for eight hours / And do an ill-paid duty", writes the shorthand typist and "typist", as the witty and melancholic poet describes herself. The special things that find expression in Mascha Kaléko's poems are the big themes such as hope and love, everyday life and Sunday existence, but also the sacred and the profane.

Present in the cosmopolitan city of Berlin: Guardini's exemplary mission

"The decision of the [Prussian] state parliament to establish a professorship for Catholic ideology at the local university has been fulfilled by the appointment of the private lecturer Dr Romano Guardini The new professorship belongs to the Catholic Faculty. The new professorship belongs to the Catholic Faculty of the University of Wroclaw in terms of budget. Its holder will be a permanent guest at the University of Berlin. The full professor Dr Romano Guardini will take up his post in the forthcoming summer semester and submit a list of the lectures he is to give," reads Guardini's blue personnel file dated 11 April 1923. It is indeed admirable that the theologian, philosopher and pastor took an unprecedented risk a hundred years ago when he set off for the intellectual and political centre of the country. The author of works such as The spirit of the liturgy (1918) or Liturgical education (1923) thus set the course for his own theological existence. In short: Guardini took up the debate with the "educated among the despisers of religion" (Friedrich Schleiermacher) in a place that seemed threatening to him: Berlin. The priest and professor not only turned his attention to the "religiously musical", but also felt responsible for those "outside the church door": "for agnostics, doubters and the desperate, for sceptics and unbelievers, indeed for the many for whom the word church hardly arouses any feelings, not even rejection" (Hans Maier).

The journey to the capital proved to be difficult: the newly habilitated private lecturer from Bonn needed a laundry basket full of paper money to buy the ticket. The thirty-eight-year-old took up his new post at the most difficult moment of the Weimar Republic: when the Ruhgebiet was occupied, democracy was under constant attack from left-wing and right-wing extremists and hyperinflation was seemingly unstoppable. The catastrophic devaluation of money is reflected in details of Guardini's personnel file, for example in the note that the young chair holder was to be paid "an advance of 3 million marks" on his salary.

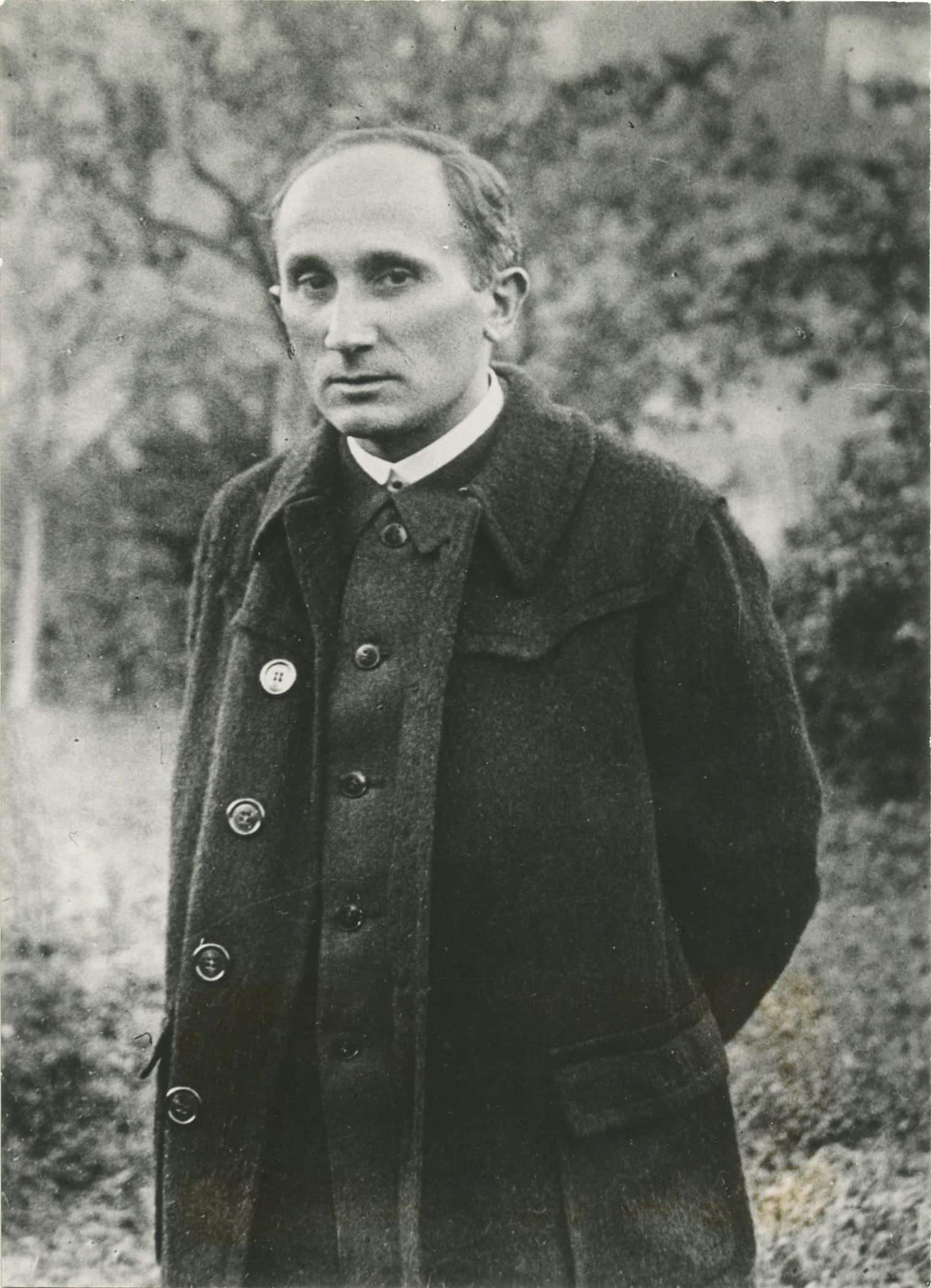

"They are treading on very slippery ground. One is convinced that they will be finished in a short time," the young scientist noted in an assessment from the Prussian Ministry of Culture. The controversial appointment of a Catholic could only be pushed through against the Protestant Theological Faculty and the Faculty of Philosophy by the Minister of Culture, Carl Heinrich Becker, using the trick mentioned at the beginning - namely disguised as a visiting professorship in Breslau. The fact that a vital Catholicism was not envisaged in the self-image of the capital's intelligentsia is expressed in the irritation caused by Guardini's appointment to the newly created Chair of Philosophy of Religion and Catholic Worldview was connected. The religious philosopher's mission in the German metropolis was unprecedented. It was orchestrated by vociferous protests, but also commented on by sensitive observations. "The lecturer himself is a slender, pale figure clad in a black priest's robe [...] and, all in all, one has the impression of a fascinating personality on longer contact [...] He is undoubtedly a true scholar, one of the best representatives that the Roman Church was able to send," a Protestant theologian summarised his observations in a dossier (Gaede, Archive of Humboldt University).

At eye level

The scholar soon succeeded in turning his professorship into an institution. With his inaugural lecture The essence of the Catholic worldview he managed to get off to a flying start, which he maintained for sixteen years, most of the time under observation, until his forced retirement by the Nazis in 1939: Together with a diverse audience - in addition to students, his lectures were attended by artists, urban intellectuals, nuns, young people from the youth movement and agnostic critics of the times - he practised what Max Scheler had given him as the key to his effectiveness before he began teaching: looking at the world with Christian eyes and telling others about it. Guardini responded to this by developing his lectures and seminars into places and opportunities for worldview, seeing and understanding, in order to - as Charles Taylor would say - point to life possibilities beyond the "secular option".

With great success as a teacher, Guardini, who came from an Italian merchant's family, sought dialogue with thinkers and disbelievers such as Socrates, Dante, Pascal, Kierkegaard, Dostoyevsky, Hölderlin, Rilke and, above all, Nietzsche. "The college is going well," he wrote at the beginning of December 1923. "I have about 200-250 in one, 100 in the other, and they listen. I speak quite positively, avoid all apologetics [...] I want to create an intellectual atmosphere in which things are more correct, perspectives and dimensions and the individual face of everything are clearer; simply Catholic." ("I feel that great things are coming." Romano Guardini's letters to Josef Weiger 1908-1962edited by Hanna-Barbara Gerl-Falkovitz, Ostfildern 2008).

It seems astonishing that the Reich Ministry of Science, which had been controlled by the Nazis since 1933, kept quiet for a long time and allowed Guardini to continue. The Protestant theologian and poet Albrecht Goes aptly speaks of a "celebration in farewell". "Just as there are stellar and decisive moments, there is the moment of remembrance of that day when Guardini interpreted the famous 'Mémorial' 'FIRE' and in it this cardinal sentence: 'God of Abraham, God of Isaac, God of Jacob - not of philosophers and scholars'. This has had a very significant impact on my life and has accompanied it."

In conflict with the NS regime

The cancellation of the chair was presumably delayed by the German-Italian friendship. However, it was in the air when the philosopher of religion, following a reference by Helmut Zenz in Alfred Bäumler's speech Spruce and us was attacked head-on by the Nazi ideologue on 27 May 1937. The professor at Berlin University since 1933 on the Chair of Political Pedagogy Bäumler, who was active in the field, declared publicly: "It is a last word when Romano Guardini continues: 'It is not what is done that is the last, but what is. [...] If one drafts a world view in which law and freedom are in such tension with each other that only the formula remains: Primacy of the Logos over the Ethos remains, then one thing is no longer possible: to include the heroic character in this world view at the end."

Bäumler is alluding to the chapter Primacy of the logos over the ethos from Guardini's first book The spirit of the liturgy on. What followed in terms of university policy were bureaucratic pinpricks such as the reduction of financial benefits and the demand to repay "inadmissibly" paid subsidies, as documented in the chair holder's personnel file. Finally, the certificate of dismissal issued "In the name of the German people" on 11 March 1939 for "the full professor Dr Romano Guardini" is fascinating to look at. Its special character can be seen from the fact that it bears the signature of the "Führer and Reich Chancellor" Adolf Hitler, applied by automatic typewriter. The signature of Prussian Minister President Hermann Göring adds further weight to the document, which announces that Guardini is to be "retired at his request". The monitored and harassed scholar then spent another four years in Berlin and felt silenced by his expulsion from the Reichsschrifttums-Kammer; he finally moved to his friend and companion Josef Weiger's parsonage in Mooshausen.

Guardini on the White Rose and resistance in the NS state

In 1945, after the catastrophe of the Second World War, the Nazi opponent was visited there by Otl Aicher, the friend of Hans and Sophie Scholl, who was later married to Inge Scholl, in order to persuade him to give speeches on the Christian world view. This invitation resulted in further speeches, addresses and publications in which Guardini contributed to the White Roseand on the resistance in the Third Reich as well as on questions of "freedom and responsibility". As early as 1946, Carlo Schmidt, who had been appointed by the French administration, brought him to the University of Tübingen, where he continued his teaching activities under the well-established label "Philosophy of Religion and Catholic Worldview". As can only be hinted at here, Schmidt, who was very familiar with the totalitarianism of the Nazi state, made fruitful use of earlier reflections from the Berlin period in his analyses: for example in The saviour in myth, revelation and politics (1945) - a text of which Hans Maier writes in the instructive foreword to the new edition: "The text is an attempt to open up the phenomenon of National Socialism from a religio-philosophical perspective - probably the only one undertaken in the immediate post-war period." (Cf. 1945 Words on reorientationedited by Alfons Knoll with the collaboration of Max A. Oberdorfer, with a foreword by Hans Maier, Ostfildern/Paderborn 2015).

Able to speak and act in a late modern society

But what about the question: Is Guardini an inspiration for theology and the church, helping Christians to be able to speak in a late-modern society? After initially being abruptly forgotten, what the theologian, who was prone to melancholy and gloom, had already said in the End of the modern era (1956): that after a "time of alienation", in which a philosophical approach had become "dogmatic", only "a later epoch can gain a new relationship to man and work" from its new prerequisites. A rediscovery of the philosopher of religion, it seems to me, is closely linked to the world-historical caesura of 1989. It tore Berlin, which Guardini loved and feared, out of the slipstream of world history and turned it back into a metropolis with global appeal. The tradition revived in 1989ff. through the initiative of the Catholic Student Community, the Catholic Academy and the Guardini Foundation and the "Guardini Chair" thus have a beacon function for Catholicism in Germany!

Soon, less than half of the German population will belong to a church. Guardini's already somewhat tattered personal file is a reminder that the young theologian dared to do great things in order to reach eye level with his present. And Eugen Biser, who was the first to pick up on a tradition that had been suppressed for 50 years with the "Guardini Lectures" in the 1990s, made the following judgement about his predecessor: he had not only become effective through the insights he imparted, but even more through the "therapeutic effect" emanating from his person.