As we all know, a short portrait should not have an operatic length, but is something like a snapshot, but certainly more than a snapshot. We have already heard a "composed short portrait" at the event with the cellist Jakob Spahn! Impressive and highly virtuosic. It gave an impression of how the ultimately unfathomable Penderecki deals with this instrument, the cello, and how he cultivates his friendship with cellist Siegfried Palm while composing. He pushes the technical demands of playing to extremes, combining performance and theatre at the same time.

An integrative personality

The virtuoso performance at the event is now followed by the dry words for the documentation in the magazine zur debatte. Let's try a cantus firmus, a theme that is characteristic of Penderecki and that can be orchestrated with examples, as it were. I will categorise these considerations under the heading "integrative". This means that Penderecki was very often concerned with an "and", with a "both-and", and less often with an "either-or"; except when quality is at stake. A few personal memories should also be mentioned. The first relates to a guest performance by Penderecki in the Regio series of events with concerts in Basel, Strasbourg and Freiburg.

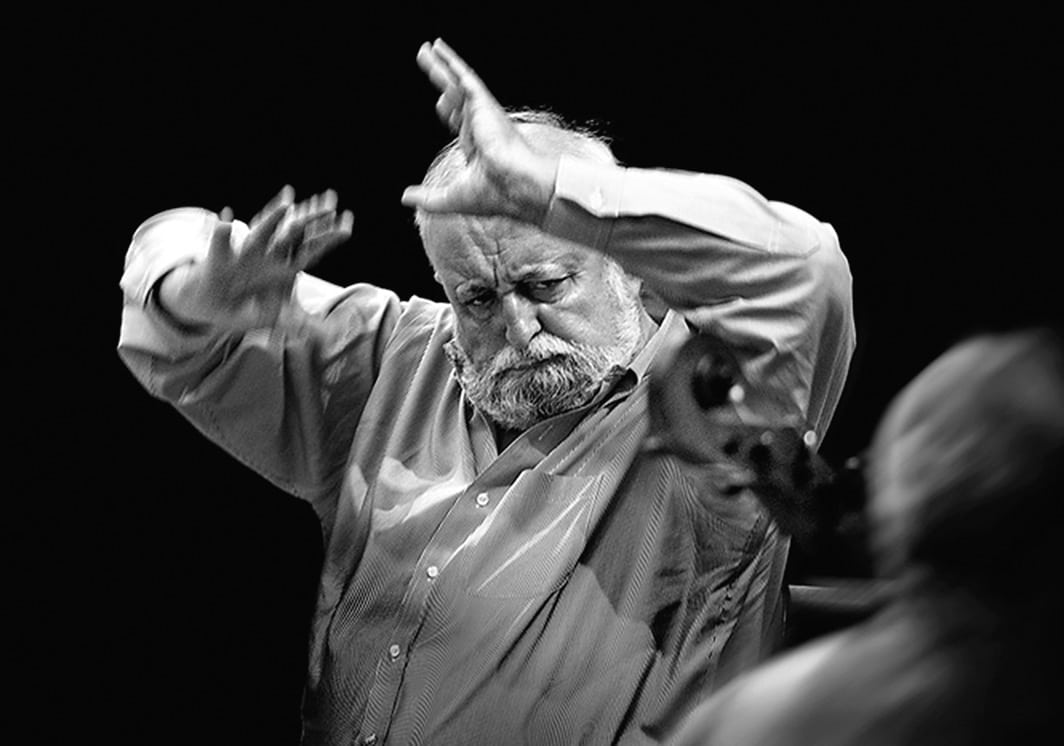

When he conducted his St Luke Passion in Freiburg im Breisgau, where I come from, with students - soloists, choir and orchestra - from three music academies, he was - as so often in his career - both the composer and conductor of his great oratorio work. And he was also a pedagogue for the participating students. All of these are already integrative tendencies. He was strict and demanding during rehearsals. But everything was at the service of the work: he demanded exactly what this Passion needed to sound good - as music of suffering and passion.

The award citation issued by the Catholic Academy in Bavaria on the occasion of the award of the Romano-Guardini Prize 2002 cites Penderecki's "own synthesis of innovation and tradition" as characteristic of his work, as well as the "musical language that can be understood across borders and cultures", with which he places "his work in the service of universal humanity and tolerance".

These are further integrations! Tradition and innovation on the one hand, and quality and comprehensibility in the sense of immediate comprehensibility on the other. It's not so easy to say what "understanding music" means. I think the piece we heard at the event opens up many possibilities of understanding. In any case, Penderecki's music is not hermetic, but has a hermeneutic basic trait. Ideas for understanding could be something like: "The composer is exhausting the possibilities of an instrument!" Or: "The interpreter is playing a joyfully composed game with his instrument; they remain different in order to try out, as it were, how intensively instrument and player can become one." I'm sure you have your own associations, all of which are justified. It is characteristic of Penderecki that he makes this possible for everyone who listens with an open mind and curiosity. To begin with, you don't have to know or recognise anything! But you can deepen your understanding with listening experiences and also with aspects of knowledge. That's also why we were at the event.

But let us return to Penderecki's integrations. His "synthesis of innovation and tradition" was quite controversial. Why? In the well-known model of "either-or", the question is: innovative and modern in the sense of an avant-garde, or a return to and commitment to tradition. Penderecki's composed answers undermine the question with the position of "as well as". This means the integration of traditional aspects into new composing, which loses nothing through such moments and perspectives of tradition, but rather gains much.

Three prizes in the composition competition

Let's take a brief look at his life: Krzysztof Penderecki was born in 1933 in the small Polish town of Debica, 130 kilometres south-east of Krakow. He came into contact with music at an early age through his father, who was a lawyer by profession and also an enthusiastic violinist. He received violin and piano lessons. After graduating from high school in 1951, he began studying philosophy, art history and literature in Krakow, but soon transferred to the local conservatory, initially majoring in violin and then in composition from 1954. He graduated in composition in Krakow in 1958 and immediately took over his own composition class.

Penderecki's first, still regionally limited breakthrough was in 1959 at the second Warsaw Competition of Young Polish Composers. He received all three prizes (one first and two second prizes) for his anonymously submitted works, "three works to be on the safe side" he said in an interview - they were called "From the Psalms of David", "Emanations" and "Strophes". The jury included such famous composers as Witold Lutoslawski and Kazimierz Sikorski.

Decades later, Penderecki pointed out in an interview that he had written one of the three submitted works right-handed and the second left-handed to preserve his anonymity; he had the third copied by a friend. The jury is said to have been very surprised by their decision. During a lengthy radio interview, he also told me this story in a humorous yet serious manner. Serious, because this was an extremely important early step in his career: a step towards emancipation and independence. The first prize at the time was a trip to the West! In the West, the city of Darmstadt beckoned as a centre of new music. But this fascination faded. Penderecki travelled to Italy at the expense of the Polish Ministry of Culture, also to meet the composer Luigi Nono.

Intermezzo: The tree expert and the sick village lime tree

I have very fond memories of this interview with Penderecki in the summer of 2003. We met at the Funkhaus in Stuttgart. While the microphones were being set up, we were supposed to chat as usual. The voices have to be audible in the technology. It's best to talk about the weather and not the actual topic, because otherwise you anticipate a lot of things and then accidentally leave them out during the interview. So we talked about Penderecki's large park with trees from all over the world - and I casually mentioned that the village lime tree in the small Black Forest village where I live is sick with something and might even have to be cut down. Penderecki really took an interest and immediately gave expert advice on how a lime tree over a hundred years old could perhaps be saved after all. I can't really remember the details. But I do remember his kindness. There were around 1600 different types of shrubs and trees growing in his arboretum at the time.

But back to the keyword "integrative", which we may not have left behind. "Integrative" also means working on different keyboards. Penderecki was able to combine his various activities in an almost virtuoso manner. Before the aforementioned radio interview, he composed at the Stuttgart Academy of Music. And afterwards there were rehearsals in Schwäbisch Gmünd for the St Luke Passion, which he had to conduct there the next day or the day after. In the interview, he said that despite the 60 concerts he conducted every year at the time, he always tried to "stay in the business of composing". He could - as a small example of his humour - not only compose in different tempi (anyone can do that!), but he could also compose in different tempi. For example, he can begin a work in andante and then, towards the end, when time is running out, complete the piece in tempo agitato.

Spiritual and secular as one

Penderecki was an exceptional figure in musical life in many respects. Like hardly any other composer - apart from Olivier Messiaen - he devoted himself to sacred music. He initially chose sacred music and twelve-tone music because both were forbidden at the time!

He wanted to counter the "avant-garde as dogma" with the "avant-garde with a human face": something individual, something historically aware. To him, copying tradition seemed as foolish as the dogma of constantly distancing oneself from it. He sought and found an unbiased relationship, rather playful and integrative. It is best to decide for yourself whether such maxims are only for composers - or whether they are not fundamental issues: socially and culturally, ecclesiastically and personally.

He said a very beautiful sentence about his St Luke Passion - when asked about the Bach tradition, which can also be a blockade. Penderecki replied: "Every composer is afraid of Johann Sebastian Bach. But I was too young to be afraid."

Penderecki's international standing was established in 1966 with his St Luke Passion: created on the occasion of the 1000th anniversary of the Christianisation of Poland and premiered in Münster Cathedral in Westphalia, the St Luke Passion entitled Passio et mors Domini Jesu Christi secundum Lucam in Latin, for which he received several prizes. In this extremely complex vocal-instrumental work, the time-honoured tradition of Passion music meets the avant-garde of the 20th century for the first time. This is also an exciting integration. The biblical theme of the Passion offers a potential of characters and affects, events and gestures as well as possibilities for reflective sympathy, which Penderecki explores in a deeply theological way with his music and at the same time stages to great effect in words and sound.

Christ's suffering and the suffering in Auschwitz

The sound experiments that were still form-founding in the avant-garde works, such as the Sprechgesang or the cluster technique, are now not abandoned, but are only used in a calculated way for individual moments and meanings, such as the choral hissing in the mockery of Jesus. Sound innovations thus function as vocabulary for fields of meaning, similar to the strange and at the same time triumphantly glistening major chords in the fortissimo at the end of the Stabat Mater and as the final chord of the entire Passion.

Penderecki's basic aesthetic-theological option is also integrative, as his Passion is based on the will to "mirror" the suffering described in the Bible in today's suffering and vice versa: "The Passion is about Christ's suffering and death, but it also depicts the suffering and death in Auschwitz, the tragic experience of humanity in the middle of the 20th century. In this sense, it should have a universal, humanistic character according to my intention and my feeling," Penderecki said verbatim.

Loner and contemporary

In one of his many interviews, Penderecki once described himself as a "loner". "I am a loner," he told the magazine Musik und Kirche in 2000, which he was to the extent that an artist and composer must be. At the same time, however, he was an alert contemporary. He took a stand and did not compartmentalise the field of aesthetics. Cineastes encounter his film music. Concert-goers encounter his sacred music.

However, he was less interested in functional church music! He saw a problematic dissonance between the church and modern music: because church services have sometimes become "banal". The devout Catholic composers - Olivier Messiaen and Maurice Duruflé, Petr Eben or Hans Zender and Penderecki - and the liturgical reform of the Second Vatican Council, that would be a tense topic in its own right, which is also about the failure of a possible integration! Penderecki shares this reserve with a number of religious composers of his generation. He was actually quite happy with Latin and Gregorian chant. "I only go to Latin mass," he said. He did not want to write church music in Polish. The answer is laconic: "Latin as a language is much easier to compose in than Polish."

To conclude: couldn't music and religion be a further synthesis, an integration? I think so, yes. And that somehow brings us to the first opera, the subject matter and discussion of which I don't want to anticipate. Just a brief comment: it seems to me that another quality criterion of music and theatre is that works develop a kind of composed "phenomenology": This is how religion shows itself with its light and with its dark sides. The fact that the human face can be distorted is something we experience in Passion music as well as in Penderecki's first opera.

"Hope" was an extremely important word for him. And perhaps this is a very special integration, namely that of "immanent" and "transcendent". Penderecki wants to show perspectives that are more than earthly. He speaks of the "labyrinth" and the various paths. "I also love the detours, because they are part of it," he says. Of course, the tendency to transcend also applies to the technique of playing: Penderecki expands the possibilities and thus enters into a dialogue with the performers, even today, I think even at every performance.

When I asked him about his keyword "avant-garde with a human face", the first response was a smile. But then also a statement with the words: "It's about personal music. Music that doesn't just come from the head, but music with feeling. That also applies to the works of my wild avant-garde time." So perhaps this is the final integration: the unified work that recognises different phases - or the successive periods of composing that, for all their differences, even contrasts, are nevertheless carried by a unified keynote. What overtones his first opera The Devils of Loudun adds can still occupy us.