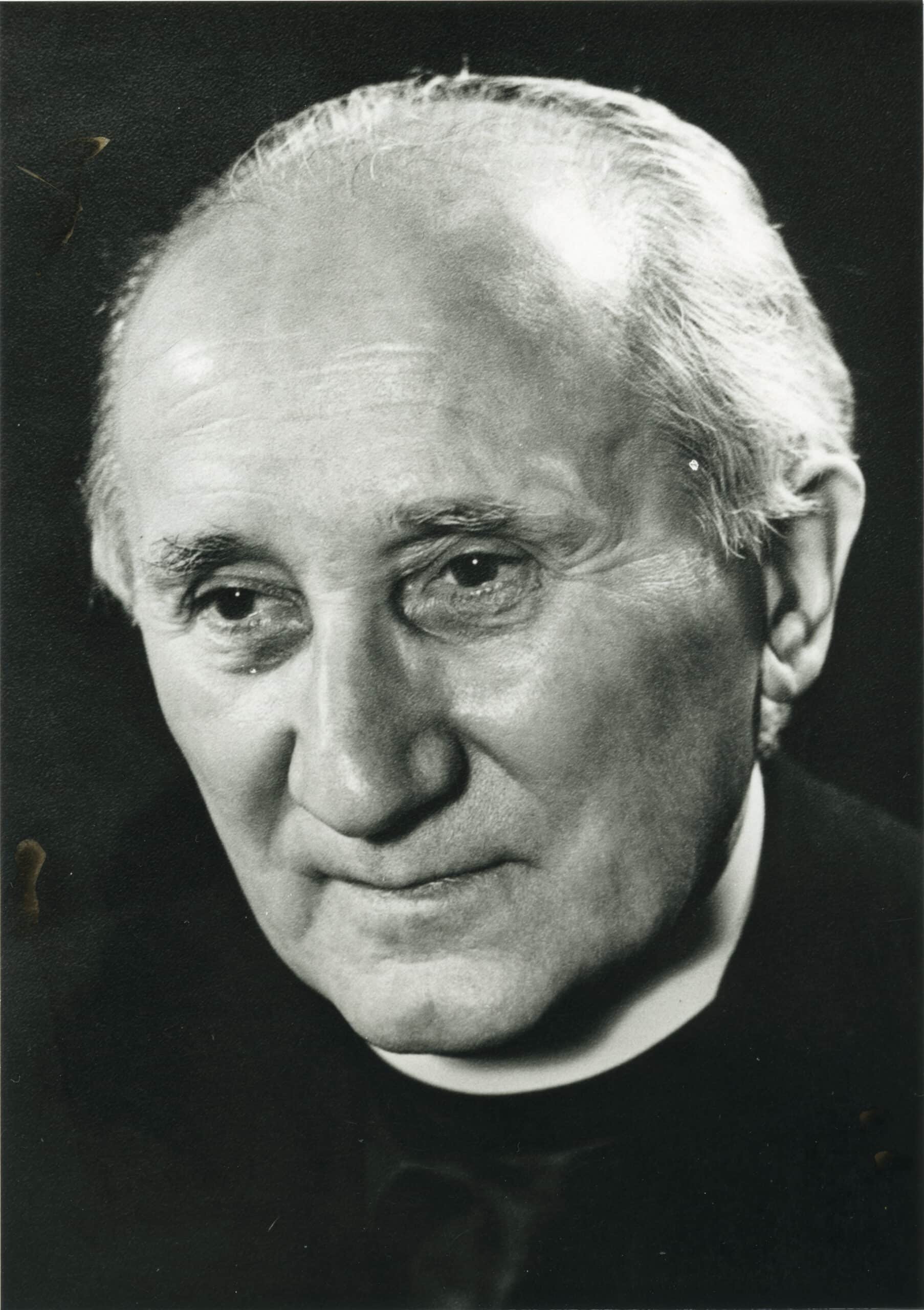

Romano Guardini's writing The end of the modern era (1950) occupies a unique position in his oeuvre. The overall short text is an occasional work and is closely related to the Pascal lectures, which were published in 1935 under the title Christian consciousness were published for the first time. In the following, the central theme of the text will be traced, with reference to the situation of the church and faith today. Furthermore, the occasional writing will be categorised in Guardini's work and the contemporary historical horizon.

Introduction: On Guardini's writing The end of the modern era

But how else can Guardini's book be characterised? The subtitle alone is significant: "An attempt at orientation". Guardini unequivocally pursues the goal of giving people orientation after the Second World War without speaking or preaching 'from above'. For Guardini, the teaching pulpit in the university and the preaching pulpit in the church are equally important in order to reach his contemporaries in terms of content. Guardini was just as affected by the collapse after the Second World War as most other Germans. Like many others, Guardini experienced the second devastating end of the war in Germany after 1918. While Guardini experienced the first years of the war in Berlin, from 1943 he lived with his friend Josef Weiger in the vicarage of Mooshausen in the Swabian Allgäu. The end of the modern era consists, as already briefly mentioned, of introductory lectures to the Pascal lecture Christian Consciousness (1935). These lectures were held in Tübingen in 1947/48 and in Munich in 1949.

This is an occasional publication, as "friends and listeners" recommended that Guardini publish these introductory lectures individually, as stated in the "Preliminary Remarks", as a point of orientation in the late 1940s. The situation is very similar with the writing The power (1951), which bears the subtitle Attempt at signposting bears. With both writings, Guardini made "attempts" to shed light on the confusing situation of the post-war years. For many people, this was the first glimmer of hope after the 'zero hour', the collapse of 1945. The end of the modern era is very densely written and refers closely to his other writings on anthropology, culture and technology.

How can The end of the modern era into the wider context of Guardini's writings? Guardini presents a kind of 'critical balance sheet' of the modern era. In it, he defines the position of man in modern times and beyond. The book is dedicated to Romano Guardini's brother Mario.

Eric Voegelin, whom Guardini would later meet in Munich after 1958, had a similar intellectual position. With his criticism of the self-redemptive character of modernity as 'gnosis', Voegelin was close to Guardini in terms of content. Both were involved in the founding of the Catholic Academy in Bavaria and the Academy for Political Education in Tutzing in 1957. Hans Blumenberg presents himself differently. A good 15 years after the publication of The end of the modern era and The legitimacy of modern times (1966), i.e. the constant legitimisation and self-legitimisation of the modern era in a 'detachment' from the Middle Ages.

But Guardini's writing also has an impact on the present day. Pope Francis quotes him in his encyclical Laudato si' eight times from The end of the modern erato criticise a false anthropocentrism in his encyclical and prove it to be harmful to people, society and the environment.

The medieval view of the world and man according to Guardini

Guardini sees the Middle Ages as a world of symbols and order: "Medieval man sees symbols everywhere. For him, existence does not consist of elements, energies and laws, but of forms. The forms signify themselves, but also, beyond themselves, something else, something higher; ultimately, the real high, God and the eternal things. In this way, every shape becomes a symbol. It points beyond itself. One can also, and more correctly, say: it comes down from above itself, from beyond itself."

This idea is also reflected in the motto World and person (1939), which Guardini took from Pascal's work Pensées "Man surpasses man by an infinite amount." Guardini shows here on the one hand man's striving for progress, but on the other hand also that man is not entirely in control of himself and is often driven by hubris. In doing so, he loses his measure and centre and ultimately himself.

Man as a person gains measure and centre by placing himself in an order, a Ordowhich was characteristic of the Middle Ages and which has a clear reference to transcendence: "In the Middle Ages, life was interwoven with religion in all its layers and ramifications. The Christian faith was the generally accepted truth. Legislation, social order, public and private ethos, philosophical thought, artistic work, historically moving ideas - everything was in some sense characterised by the Christian church."

Romano Guardini shows an open understanding of the Middle Ages, but in no way glorifies or romanticises this epoch. For Guardini, it is not possible to turn back the wheel of history. Man's existence can only be directed towards the future.

The modern view of the world and man

For Guardini, modernity is characterised by an unfathomable "trinity": nature, subject and culture: "Modern consciousness answers the question as to how existence exists: as nature, as a personal subject and as culture.

These three phenomena belong together. They are mutually dependent and complete each other. Their structure signifies an ultimate, beyond which it is no longer possible to fall back. It needs no justification from elsewhere, nor does it tolerate a norm above itself."

The three key concepts of nature, subject and culture characterise modern man. To a certain extent, they build a house around him in which he establishes himself temporally. However, modern man often overlooks the fact that the finite becomes absolute if no further norm outside or above nature is permitted.

In contrast to this is the self-abasement of modern man: "Modernity also endeavours to move man away from the centre of existence in terms of meaning. For them, he no longer stands under the eyes of the God who encloses the world, but is autonomous, has a free hand and his own pace - but he also no longer forms the centre of creation, but is just any part of the world. On the one hand, the modern view elevates man, at the expense of God, against God; on the other hand, it has a herostratic desire to make him into a piece of nature that is not fundamentally different from animals and plants. Both belong together and are closely connected in the change of the world view." Uncertainty and indeterminacy in reality put people in a situation where they no longer trust themselves, the world and therefore also God. After the intoxication of misunderstood autonomy, the resulting excessive demands on people end in self-abasement.

According to diary entries from 10 April 1945, i.e. before the end of the war, Guardini wrote in his text Reports about my life on absolute, non-historical Platonism and the "specific dangers" of Platonic thought: "In modern times, two strangely contradictory and yet apparently mutually dependent tendencies are simultaneously awakening and growing up.

On the one hand, man detaches himself from God, claims independence and self-sufficiency for himself. The whole thing intensifies into an endeavour to dismiss God, to do away with him, even to 'kill' him, in Nietzsche's words ... At the same time, however, the same man degrades himself, seeks to prove by all means that he is only a piece of nature, that he is descended from the animal, that he consists of matter. The dignity of man is kept above him. Ultimately, he does not live out of himself, but from above himself. He is the 'image' of a being. As soon as he denies this and falls away from the One whose image he is, he loses the reference point of his being, his honour and the measure of his existence. Then 'God abandons him to his desires ...' (Romans 1:24)." In the modern age and at its end, man thus hovers strangely between overestimation (detachment from God) and underestimation (self-abasement in the material). This is how Guardini characterises man and his life situation in a very topical way, an existence between extremes that can no longer reach a balance.

Another result of the fundamental insecurity of modern man is the need to justify faith in the modern age, which not only affected us in the middle of the 20th century, but also today: "Christian faith is thus increasingly forced into a defensive position. A number of beliefs seem to come into conflict with the real or supposed results of philosophy or science - think, for example, of the miracle, the creation of the world, God's world government - and modern apologetics emerges, both as a literary genre and as an intellectual attitude. Previously, revelation and faith were simply the basis and atmosphere of existence; now they have to prove their claim to truth. But even where it is established, faith loses its calm self-evidence. It becomes strained; it emphasises and overemphasises itself. It no longer feels itself to be in a world that belongs to it, but in a foreign, even hostile world." Guardini rightly speaks of a "conflict" that people today have to resolve between propositions of faith and knowledge about the world in order to be able to survive in faith. If people perceive faith as a reasonable approach to reality that does not, however, follow purely scientific principles, a bridge can be built between religious faith and the sciences via the idea of one and unifying reason. However, this bridge is all too often only achieved through a strained self-justification of faith.

The resulting cascade of questions is of lasting topicality: "What about God and his sovereignty if modern man's experience of freedom is right? What about the required autonomy of man, if God is God in essence? Does God really work if man has the initiative and creative power that modernity claims? And can man act and create when God is at work?

If the world is what science and philosophy see it to be, can God work in history? Can He then lead providence and be Lord of grace? Can He enter history and become man? Can He establish a foundation in it that faces human things with divine authority, the Church? And again: Can man have a genuine relationship with God if the Church has authority? Can the individual come to God in truthfulness if the Church is for everyone?

These and similar problems are reflected in the religious life of the time.

Especially on the inside."

Questions are certainly not answers. But Guardini presents us with The end of the modern era The book also provides us with answers that can give us a perspective that goes beyond everyday life, even in the current crisis situations of the church and faith. Here, too, the relationship between God and man, freedom and authority and the understanding of truth play a central role.

The end of the modern view of the world and humanity and "what is to come"

Guardini perceives the downfall after the Second World War as a crisis, i.e. as a decision-making situation. He does not analyse the character of the modern era as a direct path to downfall through the Hitler regime. For Guardini, the ideology of National Socialism is more of an epochal break than a consequence of intellectual history, as Theodor W. Adorno sees it. Rather, the crisis of the "Third Reich" leads us to see the problems of modern times more clearly and to judge them correctly, to counter their false optimism about progress with an honest pessimism and thus to arrive at a true judgement of the human situation. This is the new beginning to which Guardini refers.

In this way, man loses the false optimism of the modern age. Through the essentially scientistic deficit of his relationship to nature and culture, he ultimately loses his relationship to himself as a subject and person, to his own creatureliness and thus to God himself.

As a result, the individual no longer has any standing in reality. They lose their sense of the connections between the whole of existence and the world and ultimately of themselves; they then lack any sense of positioning. The person becomes placeless and thus unstable. As a result, they also lose their deceptive optimism about progress.

For Guardini, the new beginning consists of an orientation in the world as a person that is open to faith.

But first, modern man becomes placeless, as Guardini says in his Pascal lecture: "Man has become placeless. He hangs somewhere. He stands with his qualities in something. With his masses in the something-much. He has slipped from the consciousness of beingness into that of pure facticity."

In The end of the modern era Guardini confirms his judgement: "Man became more and more random, 'somewhere'."

But it is not only the lack of place that burdens people. It is at least as much the anti-Christian character of the time after 1945 until today: "Thus a non-Christian, often anti-Christian way of life emerges. It asserts itself so consistently that it simply appears to be the norm, and the demand that life must be determined by revelation takes on the character of ecclesiastical encroachment. Even the believer largely accepts this state of affairs, thinking that religious things are a matter for themselves, and worldly things likewise; each area should be shaped by its own nature, and it must be left to the individual to decide how far he wishes to live in both." A little later it says: "The coming time will create a terrible but healing clarity in these matters [radical unchristianity]." And: "Where the coming age opposes Christianity, it will take it seriously. It will declare the secularised Christianities to be sentimentalities, and the air will become clearer. Full of hostility and danger, but clean and open."

What does Guardini mean by this? Certainly not pure pessimism. Rather, Guardini sees the opportunity for modern man to regain an undistorted view of reality in the clear frontal position against the anti-Christian and to carry faith into the present with new argumentative strength.

Ultimately, Guardini is concerned with a new beginning, which must, however, face the danger of atheism. Here Guardini warns with Nietzsche: "One can say with the utmost justification that from now on a new phase of history begins. From now on and forever, man will live on the edge of an ever-increasing danger that affects his entire existence."

The beneficence of a shallow faith or a comfortable agnosticism, which lets the 'Dear God be a good man' (at best), is by no means sufficient today to counter the crisis of faith with hope and a living faith: "The non-believer must emerge from the fog of secularisation. He must give up the beneficence that denies revelation but has appropriated the values and powers developed by it. He must honestly realise existence without Christ and without the God revealed through Him and experience what that means. Nietzsche already warned that the modern non-Christian has not yet recognised what it really means to be one. The past decades have given us an inkling of this and they were only the beginning.

A new paganism will develop, but of a different kind than the first. Here, too, there is an ambiguity that is evident, among other things, in the relationship to antiquity. Today's non-Christians are often of the opinion that they can scrap Christianity and look for a new religious path based on antiquity. But in this he is mistaken. You cannot turn back history." Here too, Guardini emphasises the irreversibility of history and the focus on the new, the coming, which man should not accept in fear, but in trust in God.

For Guardini, the solution and the new beginning lie primarily in reclaiming the personhood of man: "Personhood is essential to man; however, it only becomes clear to the eye and affirmable to the moral will when the relationship to the living-personal God is opened up through the revelation of God's filiation and providence. If this does not happen, then there is an awareness of the well-born, noble, creative individual, but not of the actual person, which is an absolute determination of every human being beyond all psychological or cultural qualities. Thus, the knowledge of the person remains linked to the Christian faith. Its affirmation and cultivation may survive the extinction of this faith for a while, but then it is gradually lost."

Man's awareness of his personhood must be reawakened and resolutely sought through faith in Jesus Christ. Faith itself demands a new decisiveness: "But the Christian faith itself will have to gain a new decisiveness. It too must emerge from the secularisations, the similarities, half-measures and mixtures. And here, it seems to me, a strong trust is allowed." This results in a renewed trust that it is God who walks the path with us as persons. In resolute faith, we are never alone. According to Guardini, this resoluteness in faith presupposes bravery: "If we understand the eschatological texts of Holy Scripture correctly, trust and bravery will form the very character of the end times." Guardini refers here in eschatological terms to Mt 24:36: "That hour is known [...] only to the Father." Guardini thus warns against an artificially manufactured eschatology, an anticipation of the end of the world that does not bring people redemption, but ideological narrowness and ultimately annihilation.

Summary: End and beginning - turning point

Romano Guardini criticises the scientistic spirit of modern times, which he sees represented by René Descartes. Man can no longer master and control this falsely weighted scientism, can no longer balance it. Asceticism is needed here. In this asceticism, which promotes a more sober view of the world and reality, a new positioning of man as a person in the world is achieved.

Furthermore, political power must never become demonic. It must have a personal face, which we must give it. Guardini is an optimist. He wants to see a new beginning after the "Third Reich" that allows people to regain their essence as a person. However, Guardini firmly rejects an intellectual regression in the sense of philosophical romanticism. The wheel of history will not be turned back! Guardini sees a clear understanding of progress and thinking 'forwards' as a way out of the disorientation after the Second World War. This requires a resolute faith. Here Guardini follows Blaise Pascal and Sören Kierkegaard, who in their time both called for an existential reorientation towards faith. The reference to revelation thus becomes newly fruitful and can - then as now - be a true alternative offer of meaning.