Censorship is often seen as a building block in the early modern development of power at a time when governments were tailored to the sovereign and his close circle of advisors. Censorship was and is associated with an aura of strict secrecy, usually combined with a blatant overestimation of the logistics on the part of censors and inquisitors working on a voluntary basis.

Monastic "poison cabinets"

Exhibitions on "locked away" books, as presented by the Bavarian State Library in autumn 2002, attracted a large audience. While the corresponding holdings of indexed literature in the Bavarian State Library are at least partly based on dissolved monastery and abbey libraries in the country that were orientated towards the knowledge context of the time, in 2013 an exhibition on banned books in the library of the Swiss Benedictine Abbey of Einsiedeln in the canton of Schwyz answered questions about how we should imagine the reading and reception practice of censored writings. In Einsiedeln, the suspicious "libri prohibiti" were not even kept separately from the general book collections; however, they were also not found in official catalogues - certainly for good reason. A look into the "poison cupboards" of former censors is therefore both topical and still promising.

Educational travellers of the Enlightenment period had already taken an interest in this, who, like Friedrich Nicolai in 1781 during a visit to the Franconian Benedictine Abbey of Banz - where the Electorate of Bavaria took over the administration of the monastery in 1803 - reported with astonishment that the cupboard containing the "libri prohibiti", which had been indexed by the Roman Curia since 1559, was open in the monastery library and that it was therefore easy to study forbidden world literature. Banz seems to have been very enlightened when it came to drawing conclusions after the opening of monastery libraries and convents for indexed literature, but this library was certainly no exception. We can assume something similar for the Upper Bavarian monastery and convent landscape; at least some abbeys there, such as Scheyern, founded in 1077 and the house monastery of the Wittelsbach dynasty, had their own sections of indexed books.

Papal-Ecclesiastical Censorship Forums - The Index Librorum Prohibitorum

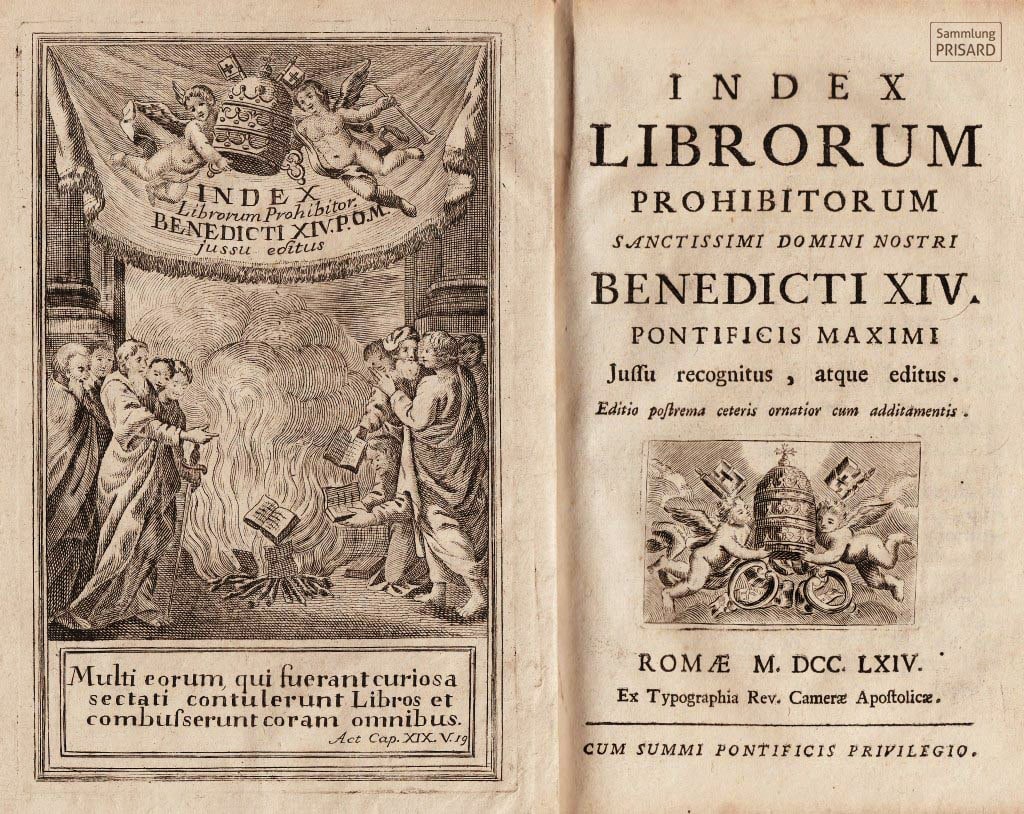

Church book bans and scripture control were not a new curial invention when Pope Pius V (1566-1572) had the first edition of the Index librorum prohibitorum published in 1559, which was valid under canon law until the Second Vatican Council (1965/66). Pope Pius V had joined the Dominican Order in 1518, acted as Grand Inquisitor against reformers and heretics from 1558 and was canonised in 1712. The appointment of six cardinals as General Inquisitors by Pope Paul III with the bull Licet ab initio in 1542 was decisive before his pontificate, centralising the supervision of censorship after leading European universities had repeatedly come to different conclusions about book bans.

Differences of opinion arose before 1559, especially in the case of works by Reformation theologians. The comprehensive list of banned books divided the censorship and prohibition orders issued by the Roman Inquisition into three categories: Firstly, the measures concerned authors (1) whose writings were banned in their entirety or (2) whose works were only banned in part or in extracts. Finally, (3) the Congregatio Romanae et universalis inquisitionis, the predecessor of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, indexed anonymously published writings. Since the Reformation, this third category included virtually all (heretical) printed works whose authorship was concealed by pseudonymisation or anonymisation. The final catalogue listed the works as heretical writings; initially there were only 62 titles.

However, there were already numerous censorship measures and book burnings before Pius V. The catalogue of sources on papal press control in modern times edited by Jyri Hasenecker does not begin in 1559, but starts with the year 1487. If we look back to antiquity and the Middle Ages, further perspectives open up. Pope Leo the Great had the heretical writings of the Manichaeans burned as early as 446. In 1121, the French theologian Petrus Abaelardus (1079-1142) was condemned at the Council of Soissons for his work on the Holy Trinity, Theologia Summi Boni. De unitate et trinitate divina to be burnt. The examples could go on and on until the middle of the 16th century. On 15 June 1520, the Roman Curia finally banned all of Martin Luther's writings with the bull Exsurge Domine.

The year 1559 marked a clear caesura in the history of ecclesiastical censorship, even though books had previously been banned. Once published, the index was updated and regularly supplemented from 1564 onwards. In its last edition in 1948, the index still comprised several thousand volumes. It only lost its validity in 1966. The list of banned books compiled at the University of Kassel provides an almost complete list of all writings indexed by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith between 1559 and 1966. The lists were compiled as part of documenta 14 in Kassel and reflect the status up to the end of December 2016. On 11 June 2017, the Süddeutsche Zeitung reported approvingly on this database, which is essential for the history of censorship: "The 'Parthenon of Books', a temple of banned books, is one of the highlights of the documenta. Germanists from the University of Kassel followed the trail of the works - and created one of the world's largest collections of banned literature".

Imperial-Worldly Censorship Forums - The Book Commissions in Frankfurt and Leipzig

The Imperial Book Inspection was established as an authority of the Holy Roman Empire to control the printing and press industry. From the second half of the 16th century, it was one of the institutionalised censorship forums - "formal" or "structural censorships" - after the Imperial Diet of Augsburg in 1530 had transferred the supervision of the printing industry to the emperor. Before 1530, the imperial diets of Worms (1521), Nuremberg (1524) and Speyer (1529) had already created the legal basis for the establishment of censorship that was detached from the church. At the same time, the first censorship authorities were established in what is now Switzerland in the 1520s. In Zurich, the city's printing works were subjected to council control in 1523. In addition, the police regulations of 1530, 1548 and 1577 structured the book market and the associated censorship-related bans on printing and distribution.

The book commissions of the empire in Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig - where it established itself as the Electoral Saxon Book Commission - were in their beginnings a response to the challenges of the media revolution and the resulting mass of reformist writings, whose authors campaigned against canon law and traditional constitutions. The success of Martin Luther and contemporary preachers and reformers would have been unimaginable without the dissemination of printed publications and pamphlets, most of which were published in large print runs. Reformation media therefore changed everyday life, especially in cities, so that one can follow the assessment of the English Reformation historian Arthur Geoffry Dickens (1910-2001) with regard to the development of censorship. The often-recognised phrase from 1974 goes back to him: "Reformation was an urban event".

Censorship now also became a guarantor of the guidelines of the Reformation by virtue of imperial privileges, which granted individual publishers the monopolised right to reprint. In Basel - where the council had officially introduced the Reformation in 1529 - the city's censorship regulations of 1578 clearly stated the purpose of future scripture control: "That therefore and hereupon/ we as soon as possible/ reformed our churches/ abolished all false dwelling/ superstition/ false worship/ and instead/ to serve the Lord God/ our hope/ created for him a favourable form/ according to his word/ as well as our faith/ Christian confession/ and confession/ and let all this go out in public truck." In Basel, as in other cities of the Reformation, the Frankfurt censorship guidelines were followed.

Bavarian censorship measures

In Bavaria, the Catholic rulers supplemented the general imperial and papal provisions on censorship from 1524. This was certainly in the interests of the imperial institutions and the Curia in Rome. The imperial supervision of book printing, the book trade and the press in the Old Empire with the Book Commission established in Frankfurt in the 16th century could not and would not prevent the need for territorial initiatives, despite a large number of enquiries and orders and the support of the Imperial Chamber Court. Furthermore, after the Council of Trent, the index system was finally codified in Catholic countries under Pope Pius V, as described above. Bavaria always accompanied the European censorship measures with its own actions. An early example of this is the catalogue printed by the Munich publisher Adam Berg in 1566. The books and writings concerning our holy religion and ecclesiastical matters that are allowed to be publicly owned and purchased in the Bavarian state.

In 1569/70, the dukes initially delegated control over the books to a religious tribunal made up of sixteen people, which prepared and implemented fundamental regulations on censorship and religion until the establishment of the Spiritual Council as a central authority in 1570/73. These activities, which led to censorship-oriented centralisation at a very early stage, were driven by a well-founded concern about the intrusion of reformatory writings. From the time of the Reformation onwards, book merchants or so-called hucksters flooded the Bavarian hinterland with pamphlets written by Martin Luther and other reformers. The rulers of both Bavaria and the Principality of Salzburg attempted to curb or even prevent the smuggling of banned books by means of general mandates. Bavaria's religious tribunal responded with a rigid decree in 1569.

"And when it is first found that the reading of evil sectarian and advocate bibles, testaments, postils, prayers and hymnals, as well as other disputes and treatises, which have hitherto been brought into German by those opposed to the faith and have come into print, are again printed and published daily by the people of our principality of the Upper and Lower Bavaria. have also been printed and published again daily/ among the citizens of our Principality of the Upper and Lower Lands of Bavaria/ have done no small harm/ in view of the fact that the translation or Germanisation of the Bibles/ thus also of the New Testament by Luther Zwinglj and his followers, Zwinglj and their successors/ have been "mixed in many different places/ with all sorts of old condemned sects/ heresies and heresies/ in almost all places".

The result was a formal ban on non-Catholic books.

The Religious Tribunal gave rise to the Ecclesiastical Council, which was initially made up of four ecclesiastical and three secular councillors from 1573. The respective dean of St Peter's Abbey in Munich chaired this body, which was responsible for denominational, cultural and educational matters. Regional bishops were not involved. In principle, the state censorship was therefore assigned to the Ecclesiastical Council, even if the legally competent Court Council demanded a say from case to case. Despite the clear assignment of the censorship system to an authority appointed by the prince, it should not be overlooked that, as in other territories, comprehensive censorship by a body focussed on the city of Munich could only be achieved with reliable and efficient middle and lower authorities.

In any case, the low volume of censorship-related business in the clerical council contrasts with Gerhard Heyl's assessment of the success of the largely practised protection of the Bavarian book market. There were no Bavarian printing towns outside Ingolstadt and Munich, so that the pre-censorship practised there, in contrast to the productive printing and imperial city of Augsburg, was not a cause for concern. However, the importation of books continued and its monitoring suffered due to overburdened customs authorities and the many exemptions granted to the court marks of the Bavarian nobility and the church. Despite numerous resolutions and decrees on book control, the Ecclesiastical Council limited itself to checking the trade fair catalogues, in which indexed books were of course not included, or to inspecting the stacks of books offered by external bookkeepers. During the 16th century, visitations were only successful in Munich, where in 1569 the ducal religious tribunal discovered banned books in more than twenty households after interrogating 150 suspects. The penalties for offences, which were mostly only directed at booksellers anyway, remained low.

In contrast to the censorship practices in the imperial cities, state intervention in the still church-dominated censorship system intensified considerably in Electoral Bavaria during the Enlightenment. In 1769, a special deputation already established under Elector Max Emanuel was made independent of the Ecclesiastical Council as a book censorship board. This ten-member committee, whose areas of work were divided into departments, could carry out visitations and confiscations as well as order fines and imprisonment, which could only be appealed to the highest authority. It had executive powers.

Elector Max III Joseph appointed academically high-ranking experts in an effort to allow "no other censorship" than the control standardised by the state, but in a selection that expressed loyalty to the court, an undogmatic free spirit and diversity and neutralisation in terms of religious order. In addition to the president and his deputy, eight censors shared the specialisms of theology, jurisprudence, philosophy, medicine, cameralistics and history. Despite this comparatively remarkable appointment of proven experts - with the exception of Karl Anton von Vacchiery, the ecclesiastical councillors were all members of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences - the effectiveness of the Book Censorship College probably did not differ that much from the model of the neighbouring imperial city of Augsburg. In view of the personnel structure of the censorship authorities, it is possible to make concessions to the image of an early modern power state consolidated by censorship, as outlined by the Munich-born constitutional lawyer Adam Contzen (1575-1634), for example.

In any case, the Spiritual Council was a mostly over-aged, honorary body whose members were engaged in labour-intensive and responsible activities elsewhere. Constellations of people in censorship bodies sometimes also brought dangers for the sovereign. In 1785, for example, the government had to remove the Bavarian court and book censor Alois Freiherr von Hillesheim from office, as he was an illuminist and publisher of the Enlightenment pamphlet Der Hausvater, which represented anything but a religious policy in line with the prince. All in all, the protection of the church and denomination, with strong support from the monasteries, convents and religious orders, was certainly on the agenda of Bavarian censorship and press policy for a very long time.

During the Enlightenment, the objective changed fundamentally. In its first year of operation, the Bavarian Book Censorship Board, which became independent in 1769, published an extensive catalogue of various books that the Churfl. Büchercensurcollegio, partly as contrary to religion, partly as contrary to good morals, partly as contrary to the laws of the state. The catalogue of 1770 comprised 16 pages and was published by the academic bookseller Johann Nepomuk Fritz.

Finally, let us study some entries on banned printed works, which emphasise the change from a primarily confessionally motivated censorship of the 16th and 17th centuries to the power- and state-supporting function of the colleges in the 18th century.

Under the letter "E" is "Emille, ou l'Education par J. J. Rousseau citoyeu de geneve. 4 Tom. Amsterdam 1762". This was Jean-Jaques Rousseau's (1712-1778) main pedagogical work from 1762, which was banned and publicly burned in Geneva, the writer's birthplace, on 19 June 1762. The pedagogical construct designed by Rousseau was considered scandalous in its statement that "natural" religion was based on everyone's experiences and reflections and that Emile did not place himself under the yoke of values imposed by the church and state in order to freely choose individually and form his own opinion.

The following entry for the philosopher François-Marie Arouet, better known as Voltaire (1694-1778), can then be found under the leading letters "V,W" in 1770: "Voltaire portatif. Pensées Philosophiques de Mr de Voltaire, où Tableau encyclopedique des Connoissances humaines, 2nd Tom, [Paris] 1766". With the work printed in 1766, the Bavarian index in 1770 surprisingly only listed one work by Voltaire, whose writings had been the constant focus of many censorship committees since the confiscation of the first edition of his Histoire de Charles XII in 1730. With his harsh criticism of absolutism, feudal rule and the ideological monopoly of the (Catholic) Church, he inevitably found himself in the crosshairs of the Inquisition. This was less true for Prussia under Frederick II than for the Bavarian electorate.

Another work by Hermann Busenbaum (1600-1668), his book Medulla theologiae moralis, facili ac perspicua methodo resolvens casus conscientiae, first published in 1645, was publicly burnt for the first time in 1757 in Toulouse, France, despite its theological title, primarily because of its detailed sections on regicide. Accordingly, it was primarily monarchical and statist motives that led to the Jesuit Busenbaum's Medulla being placed on the Bavarian Index in 1770.

On the other hand, the indexing of many writings by leading Enlightenment thinkers and philosophers in 1770 does not allow the conclusion to be drawn that the Electorate of Bavaria's book censorship had already closed the chapter of European "confessional wars". For example, the list of banned books includes two critical editions printed by Joseph Aloysius Crätz in Munich in 1768 by the Jesuit, theologian and cardinal Roberto Francesco Romolo Bellarmino (1542-1621), who died in Rome in 1621. Although Bellarmino was regarded as the main advocate of Roman Catholicism in the 16th century, supporting and justifying papal supremacy in matters of faith, fundamental conflicts between the Jesuit order and Pope Sixtus V (1585-1590) led to disputes over the issue of the popes' temporal possessions. As a result, Bellarmin's treatises were placed on the papal index for the first time in 1590. In 1770, some of Bellarmin's works were also taken unseen from the papal index, which was still characterised by religious and confessional politics, although the distribution of the work in Bavaria was barely measurable. This included the Italian-language Bible edition Biblia (la Sacrosanta) in lingua Italiana, Cive il Vecchio e nuovo Testamento & c., Norimberga 1712, despite being commissioned for the Franconian imperial and printing city of Nuremberg.

Municipal censorship - The parity printer, trading and imperial city of Augsburg

Finally, let us take a comparative look at a city in which denominationally based censorship measures played a role from the middle of the 16th century due to a council constitution based on parity, but were not applied against Catholic or Lutheran content. Nevertheless, dissenting content in sermons was regularly censored for printing in the city's church regime. Overall, Augsburg was one of the imperial cities that created a formal censorship college as early as the late Middle Ages, with records dating back to 1474.

Like other offices, censorship was soon subject to parity appointment rules, which applied de facto from 1555 and from 1648 also to the appointment of municipal deputies "zur bücher-censur". They were observed when the patrician upper classes were elected as well as for the assessors elected from the town community, who acted as "advocati" in censorship matters. The censorship office, which had evolved from older committees of privy councillors and school lords, changed its composition when passing judgement on religious writings. Responsibility was organised in such a way that only the two councillors had to decide on religious matters, but all four censors had to decide on political issues. The Augsburg censorship office therefore had a special status in the context of the confessionalisation typical of the time, as it had to be concerned above all with achieving a balance. In 1598, a council decree on biconfessionalism accordingly stated: "The three booksellers shall be instructed and ordered by a gentleman burgomaster in the town hall not to carry any other theological books in their cathalogis, nor to bring them into the town, nor to sell them, other than those of the old catholic religion and the pure augspurgian confession, while avoiding serious punishment [...]."

The denominational status of the censors differed from that of the media-relevant printers until 1740. While 70 % of the city's population had been Protestant during the Thirty Years' War, the church records show that Catholics outnumbered Protestants at the beginning of the 18th century, which was also reflected in the printing town. While the denominational ratio among printers around 1650 was still three or four to one in favour of the Protestants, by 1738 it had changed to an almost equal ratio of seven to six. Among bookbinders, the denominational affiliation shifted even more rapidly. In 1653, the ratio was still 5:3 in favour of Lutheran master bookbinders, whereas by 1720 the ratio had changed to 18:8 in favour of Catholics.

As an honorary municipal office, the censorship board lacked executive control rights. A relationship of dependence on the council and the mayor's office existed at all times. In extreme cases, this also led to the council imposing sanctions on the censors in the event of negligence or misbehaviour. In 1632, against the backdrop of the expulsion of the Catholic printer Andreas A(p)perger (1598-1658), the censors were fined because "as elected censors, they allowed highly potent famos writings to be printed in all laws, Reichstag decrees and police orders". In 1797, the council counsellor Franz Anton von Chrismar, who had also written numerous legal opinions on behalf of other territories, was also expelled from the censorship council as he had repeatedly failed to sufficiently censor council calendars.

The municipal college of censors with its police-state-peacemaking mandate remained strictly parity-oriented until mediatisation, despite changing confessional quotas in the citizenry. Accordingly, parity in Augsburg was not to be interpreted in the sense of balanced confessional numerical arithmetic, "but according to the content of the Instrumentum Pacis as legis pragmaticae et fundamentalis, the Catholic has as much right as the A. Conf. relative. [...] Nor is he permitted to set up new printing presses any more than the latter, but in the case of a vacant printing press, the Catholic member has the same right as the A. Conf. Society has the same right as the A. Conf. related. With what evidence of truth can it then be asserted so boldly that such a statute was granted to the Cathol. Burgers' children be prejudicial before their Aug. Conf. relatives?"

Results

With the phenomenon of general book and writingAll members of the old empire were confronted with the consequences of censorship, the banning and indexing of "unfavourable" printed matter and the granting of imprimaturs by the sovereigns of the land in a form that was to be nuanced both territorially and institutionally. Cities, ecclesiastical and secular imperial estates and mediate rulers were, due to the high fluctuation of printed matter and the transnational distribution of books, tracts, pamphlets, pictorial documents (engravings, broadsheets, paintings), calendars and other "censorship-worthy" written media, in a field of relations that still represents a desideratum for historical research on early modern statehood with regard to censorship practice.

The imperial supervision of book printing, the book trade and the press with the book commissions in Frankfurt and Leipzig could not and would not prevent the need for territorial initiatives, despite a large number of requests and decrees. The Duchy and the Electorate of Bavaria took advantage of this federal opportunity, as did the imperial cities (Augsburg) and other princely states, to enact their own censorship laws. At the same time, the Index librorum prohibitorum enacted by the Roman Curia in 1559 was still formally in force until 1966, but, like the papal calendar reform, it was initially received only hesitantly, particularly in the Protestant regions of the Old Empire.