For a long time, "power" was not an explicit topic in Christian social ethics. People were more concerned with creating an ideal theory of how the world should be from a bird's eye view than with looking at the obstacles and conditions on the way there. At present, however, we are clearly realising in church and society that this is not enough.

An era of escalating power conflicts

- Autocratic power structures have been spreading around the world for around 15 years and are driving democracy onto the defensive. Undisguised geostrategic striving for power leads to wars and makes efforts towards understanding, dialogue and peace come to nothing. The "new right" and so-called "neo-realism" had already seen this coming at the turn of the millennium and criticised the supposedly naive idealism of cosmopolitan ethics.

- The exposure of the abuse of power in the church - be it sexual, spiritual or institutional - has highlighted the blatant difference between claim and reality and set in motion a process of massive loss of trust, the end of which is not in sight. Extremely asymmetrical power structures between women and men and between clergy and laity are defended by some as an indispensable part of Catholic tradition and denounced by others as incompatible with the Gospel. From an ethical and systematic perspective, the Synodal Way is a debate about power conflicts in the Church.

- A third aspect of the topic's particular topicality arises from the ecological diagnosis of the present: the expansion of man's power over nature has been so successful in recent centuries that it threatens to tip over into its opposite and - for example in the form of climate change - is directed against man himself. This ambivalence of power, as practised by the expansive modern age over the last 500 years, was critically analysed by Romano Guardini as early as the 1950s in his work The Power and was recently taken up programmatically by Pope Francis in his Apostolic Exhortation Laudate Deum of 4 October 2023 as a "technocratic paradigm" that is the root of ecological and social aggression.

All of this is an opportunity to ask sober questions about the complex ways in which power is dealt with. Power is a key issue in understanding the current upheavals in the church and society. We seem to be heading towards an era of escalating power conflicts.

The public debate is dominated by a negative concept of power. However, power is omnipresent and also has its good and indispensable sides: After all, wherever people live and act together, phenomena involving the exercise of power play a role. Without power in the sense of the ability to influence the thoughts and actions of others and to control processes in a targeted manner, coordinated coexistence is not possible. The decisive factor is whether power is exercised as an instrument of oppression and heteronomy or communicatively as an understanding in which a collectively shared will or at least cooperative action crystallises. It depends on how power is exercised. Appropriate ethical reflection on power requires an examination of theories of power as well as an analysis of concrete practices of power.

Is abuse of power in the church's DNA?

Since the Constantinian revolution, the church has often sided with the powerful and has itself become an institution with an affinity for power. This is in tension with the biblical option for the poor and means that the church's approach to power is deeply precarious. Against the backdrop of sexual and spiritual abuse of power, Bishop Heiner Wilmer of Hildesheim stated in 2018 that the abuse of power is in the church's DNA. By this he means that the problem cannot be adequately understood as a moral failure of individual priests and employees, but also has structural causes. An image of the church that is fixated on the aspect of holiness and ignores the fact that the church is always also a community of sinners encourages the suppression of the darker sides.

Gregor Maria Hoff, who sees the Catholic Church in a "sacralisation trap" in view of its abuse cases, offers a fundamental theological deepening of this diagnosis. In order to understand the problem, a fundamental analysis of the power-power imbalance as a signature of the relationship with God is needed: "Religious systems of meaning are fundamentally power-shaped, because they coordinate the power-power imbalance of life in the permanent risk of death. In this way, religious faith takes on the form of a sacral power." He formulated it this way in March 2019 in his lecture Sacralisation of Power. Theological Reflections on the Catholic Abuse Complex at the Study Day of the Spring General Assembly of the German Bishops' Conference. Faith is hope in the power of love in the face of the awareness of one's own powerlessness. "This constellation of power and powerlessness makes believers almost infinitely vulnerable. [...] This enables the specific abuse of priestly sacral power. [...] Independent sacral power increases systemic self-sacralisation," Hoff continues.

Faith means giving trust and thus making oneself vulnerable. The believer becomes dependent on the power of the one he trusts. Since God has also made himself vulnerable, even to the point of the cross, this relationship is transformed from a one-sided dependency into a reciprocal relationship. Believers are vulnerable because their relationship with God is mediated by the church and its representatives. God is vulnerable because any disregard for human beings also hurts the incarnate God. By becoming man, God has emptied himself of his power. He does not want to overpower and force, but rather an encounter with man at eye level. Only this enables a response out of freedom and love and not out of submission. This paradoxical power of powerlessness is the guiding standard for a Christian existence and all church activity. It is demanding and always jeopardised in many ways.

Clericalism is a systemic self-immunisation that blinds us to the abuse of sacred power. It promises to mediate God's grace in exchange for subtle acts of subjugation. The blatant asymmetry of power in the Catholic Church in favour of men is increasingly perceived by many women and men as a violation of the principles of justice. Anyone who claims that the hierarchical gender difference is at the heart of the biblical faith is shifting the problem that this one-sided distribution of power can in principle be exploited to the core of the faith. The polemical defence against the concerns of feminist theology that persists in parts of the Catholic Church to this day is an indication that the dispute over the interpretation of the Bible, images of God and the understanding of ministry is also about highly sensitive power struggles. It is not enough to spiritualise the problem of power with a rhetoric of service and love and a reference to Christ, whom the priest represents in his pastoral ministry. Binding structures of power control are also needed in the church, including enforceable rights, transparent procedures in conflicts and participation in important decisions. Without such a structural change, there is a risk of further erosion of trust and an unstoppable exodus from the church.

Against this backdrop, the results of the World Synod on the Synodal Church in October 2023 are positive in part, but clearly too half-hearted overall: the ambivalences of episcopal power were named and measures to limit them were called for; in contrast, there was hardly any consensus on the asymmetrical distribution of power between the sexes. The issue of sexual abuse was also still approached rather defensively. It is a huge challenge for the Catholic Church as a global church to reach an intercultural understanding on the emotionally deeply rooted issues of gender justice, sexual ethics and dealing with power.

Crossing peace ethical borders

Love of enemies beyond unworldly ignorance of power conflicts

The Jesuanian commandment to love one's enemies appears as a pointed antithesis to any striving for power. For Friedrich Nietzsche, love of one's enemy is an expression of weakness. Postulating it contradicts the law of life, in which the strongest prevail, which is often harsh and cruel, but ultimately serves evolutionary upward development. Sigmund Freud picks up on this and comes to the conclusion in his psychological analyses that the aggression suppressed by the moral commandments of the super-ego is then often discharged unconsciously and uncontrollably elsewhere, e.g. in wars. Is relentless power struggle the law of life? Is the commandment to love one's enemies naive and unworldly?

It is worth taking a closer look at the biblical findings: The attempt to defuse the conflict by framing love of enemies only as a high ethos for religious "achievers" such as monks or saints is inadequate. Joachim Gnilka describes the commandment to love one's enemies as the "culmination of Jesus' ethics", he writes in his book on the Gospel of Matthew, published in 1986.

It does not meet the enemy in the form of an aggressive test of strength, but in a willingness to renounce violence and goodwill. However, the attitude of love for the enemy only remains morally qualified as long as it differs from resignation and a passive, defenceless surrender to fate. Love of one's enemy aims to defame and reconcile. It arises from its own kind of courage and strength. It also has a strategic component: it wants to make injustice visible as injustice by interrupting the interaction at the level of violence. Its aim is not to defeat the enemy, but to overcome or at least limit hostility as such.

Strategies of non-violent resistance

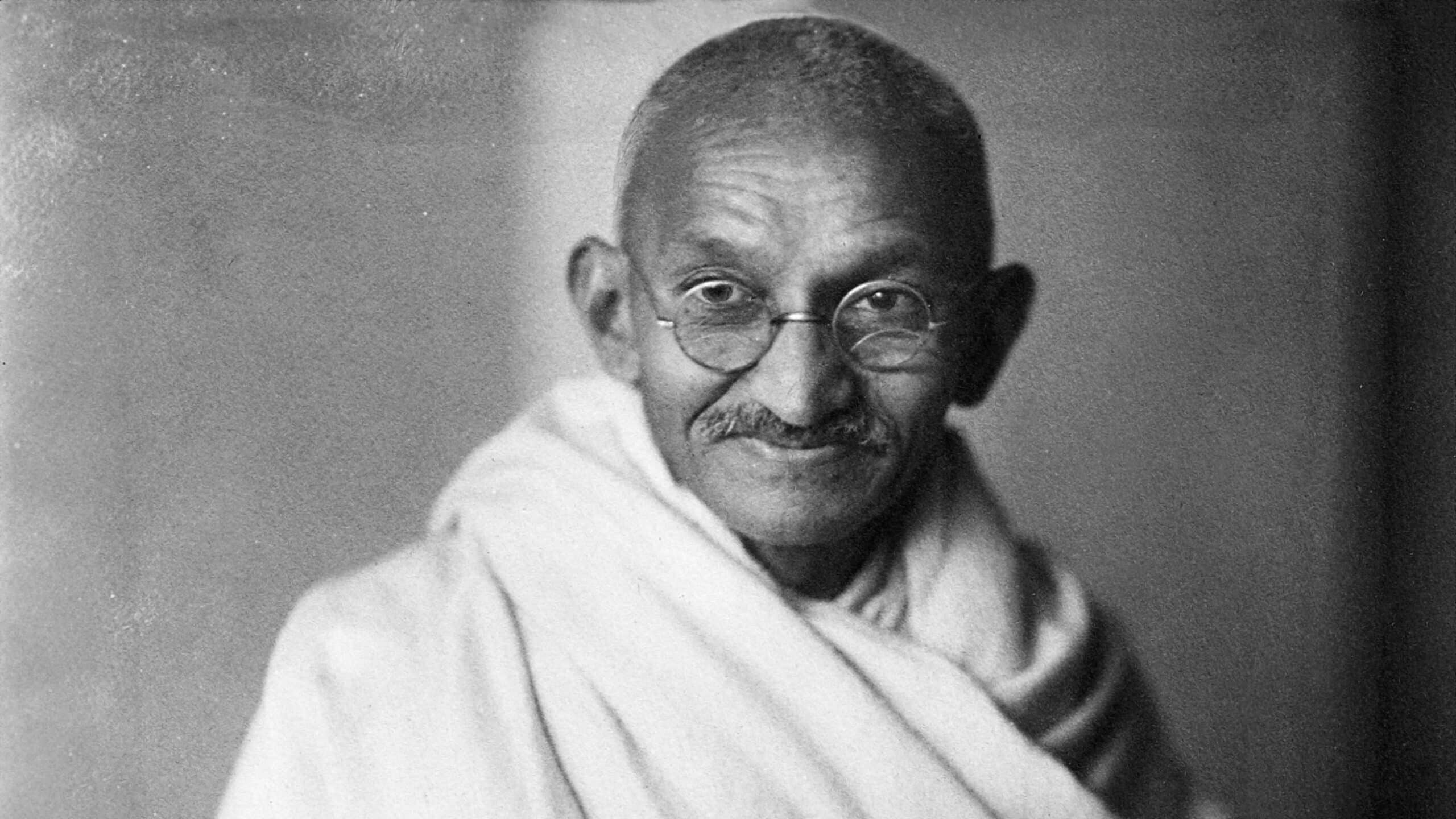

Inspired by the Sermon on the Mount and the Hindu principle of ahimsa, Mahatma Gandhi developed the power of the powerless into a political strategy. It breaks the cycle of violence through the method of non-violent resistance. The consistent renunciation of armed power makes the opponent's violence visible as injustice. It challenges his conscience and the judgement of the public. Gandhi was certainly power-conscious, he discovered and knew how to utilise the power of the media and also the normative power of the British people's high sense of justice, which he addressed. He was militant, but not in reliance on the power of brute force, but on the superior power of law and normative consciousness. He and his fellow fighters were prepared to pay the high price on the long road to the recognition of their rights: They exposed themselves defencelessly to violence and accepted imprisonment as well as the risk of being murdered. In the end, they were successful.

Anyone who surrenders to the power of the enemy in non-violent combat needs the utmost courage. He or she must reckon with cruelty, torture and imprisonment. However, the method of non-violent resistance has proven itself countless times in India and since then as a revolutionary and peacemaking force. But it must also be soberly realised that this is far from always successful. For example, more than two thousand demonstrators calling for non-violent resistance were murdered at Tiananmen Square in Beijing in 1989.

In Russia, too, all opposition is currently being consistently and successfully suppressed. In order to legitimise the oppressive exercise of power, an enemy image is needed to which aggression can be directed. The "Putin system" has identified the West as such an enemy. Ukraine's striving for independence is interpreted as Western influence. President Putin only seems to understand the language of power in the Ukraine war, so that the hope of resistance from civil society alone is proving fruitless. I discuss this controversial and complex debate in more detail in Der Ukrainekrieg als Herausforderung zur Weiterentwicklung christlicher Friedensethik, in: Ethik und Militär 2 from 2022 and in my article Nationalistische, religiöse und moralische Identitätskonstruktionen als Legitimation im Ukrainekrieg, in Münchner Theologischen Zeitschrift, 73, also published in 2022. (See also Vogt, in zur debatte, 1/2022, p. 40 ff.)

Opposition leader Maria Kolesnikova has been imprisoned in Belarus since 2020. She was sentenced to eleven years in prison on trumped-up charges of extremism and incitement to subversive behaviour. Since then, she has been largely cut off from the public and her health has suffered greatly under the conditions of detention. It is possible that the failure of non-violent resistance is more common than success. However, there are also encouraging examples: For example, the overcoming of apartheid in South Africa, for which Nelson Mandela played a key role. After 27 years in prison, he declared political reconciliation between blacks and whites to be his central political goal without any bitterness and was elected president. This is a testimony to the spiritual power of reconciliation.

Even in the current deadlocked situation in Israel, there is an urgent need for a way out of the spiral of escalating power conflicts. Yuval Harari formulated an illuminating analysis of this in the Süddeutsche Zeitung of 26 October 2023: Hamas wants escalation, it wants as many Israelis and Palestinians as possible to die, for hatred and violence to escalate and for reconciliation to become impossible. The immediate cause of the massacre on 7 October 2023 was the preparation of the peace treaty with Saudi Arabia, which Hamas wants to prevent with all its might. Israel can only win the war if it has a political plan. "Do such initiatives have any chance of being realised? I don't know. But I do know that war is the continuation of politics by other means and that Hamas' political goal is to destroy any chance of peace and normalisation. And that Israel's goal should be to preserve any chance of peace. We must win this war instead of helping Hamas achieve its goal." Harari's contribution seems groundbreaking to me because it is not based on an idealistic trivialisation of the brutality of power conflicts, but on a sober analysis of the destructive calculation of power on both sides and the need for a political plan.

Power under the sign of sacrifice

The ethical and political culmination of the power of the powerless is demonstrated by the fact that human rights cannot be silenced precisely when they are violated and thus prove to be a benchmark for critical power control. Human rights are formulated because they are violated. It is precisely in this negation that they represent the voice of the silenced, the cry of the unheard, a power that cannot be domesticated

from nameless powerlessness.

It is only here that the theological significance of human rights comes to light. They are "a place to speak of God here and now, in the sign of the touched dignity of human beings". This quote comes from Hans-Joachim Sander's book Macht im Zeichen der Opfer. Die Gottesspur der Menschenrechte from 2004, published in: T. Eggensperger/ U. Engel/ F. Prcela (eds.): Menschenrechte. Socio-political and theological reflections from a European perspective.

It is precisely when human rights are violated that it becomes clear that they are derived neither from political recognition nor from biological conditions, but transcend everything political and biological. Speaking of human rights as the right of the disenfranchised becomes a new form of God's speech. In the sign of the cross, God has established the power of powerlessness. In the call to discipleship, he enables people to make this grammar of powerlessness effective through their solidarity.

Hans-Joachim Sander, dogmatist in Salzburg, argues in favour of a paradigm shift in the theological approach to human rights: The starting point cannot be the supposed necessity of a specifically Christian justification, as this can all too easily be misused for the enforcement of religious power and the attempt to imprison God in the particularisms of religious communities. This would in fact thwart the associated peace project, for which human rights serve as a decisive basis for understanding between different nations, cultures and religions. However, as the secular, enlightened vision of human rights was also cruelly destroyed in the 20th century, the only way out is from the victims "under the sign of the dignity that has been touched", said Sander. Accordingly, the validity of human rights cannot be sufficiently understood from the abstract discourse of justification, but always requires recourse to concrete struggles in defence against injustice - this is the decisive point of Hans Joas' "genealogy of human rights" in his book Die Sakralität der Person. The power of human rights to criticise domination only gains its universal and concrete significance in the context of the victims.

Sander's contribution is based on Michel Foucault's analyses of power and Giorgio Agamben's homo sacer thesis. He understands the revelation of God in the injured, naked body as a bridge from human rights to the Christian doctrine of the cross and redemption. The revelatory quality of human rights can be seen in the negation of violated human dignity, whose cry cannot be silenced. "Dealing with human rights means finding a new language for God's presence. It means seeking out his presence among people today. [...]

The struggles for human rights are also about God's place in today's world," writes Sander again. If there is a chance to reach an understanding beyond the escalation of power conflicts in the church, in Germany and worldwide, then it is the unconditional recognition of the unconditional and equal rights of all people.

Dignity of every human being.

Structures of subsidiary power limitation

The social principle of subsidiarity is a compass for structures of power limitation and at the same time for the use of power as an enabler of freedom. It aims to promote existing competences and to strengthen the personal responsibility of the individual and the small unit, whether through restraint where the smaller unit - whether individual, group or institution - can carry out its tasks itself, or through assisting support where this is necessary. Power is used to enable the subordinate units to act as independently as possible. Subsidiarity is aimed at empowerment, i.e. increasing the power resources of subordinate or marginalised members of society.

However, the principle of subsidiarity has not yet been consistently applied in the church - as Ursula Nothelle-Wildfeuer harshly criticises in her text Glaubwürdig Kirche sein? The principle of subsidiarity in the church. The principle of subsidiarity touches the very foundations of the church. It is of particular importance for the church precisely because of its hierarchical structure, so that it does not disenfranchise the simple faithful. Subsidiarity aims for unity in diversity, for a healthy pluralism in relation to the hierarchy beyond authority-centredness towards the protection of personal responsibility and participation of the subordinate units.

The principle of subsidiarity is a prohibition on usurping authority that limits the intervention and power of higher-level authorities to the extent that is helpful for the subordinate units to increase their ability to act. At the same time, it is a requirement to provide assistance that obliges the higher-level authorities to support and coordinate the subordinate units so that they can overcome their problems in a targeted manner and act cooperatively.

Subsidiarity aims to ensure that solidarity-based help is not misused paternalistically to create dependency and thus to exploit positions of power. It is based on a communicative concept of power that does not impose power on those who need help, but supports them in such a way that their own potential is realised and activated. It is the benchmark and path to a freedom-centred use of power. Subsidiarity calls for "salutary decentralisation" (Francis), a rethinking of Catholicism that is open to pluralism as unity in diversity and participation instead of a focus on authority.

Power in the service of care

Where there is power, there is always the potential danger of abuse of power. This often happens unconsciously and in a subliminal way. The holders of positions of power in society generally endeavour to maintain or increase their distance from less powerful people. The practical significance of this observation is obvious: the top of an organisation (a trade union, a church, a company) becomes alienated from the base if it does not consciously and systematically counteract this tendency. Such alienation from the grassroots can often be observed in the church hierarchy in particular, but also among secular rulers in politics, business and society or, for example, academics who hide behind the power of knowledge.

The use of power often leads to a devaluation of the performance of subordinates. Those who have a lot of power try to downgrade the work results of their subordinates or attribute them to themselves. In the Catholic Church, this is currently particularly virulent with regard to recognising the work of women, volunteers and lay people. Against the background of his experience with power conflicts in the religious tradition, the former provincial of the Jesuits, Stefan Kiechle, summarises by emphasising how important it is for successful leadership responsibility to talk honestly, directly and truthfully about different perceptions. Taking a close look and taking unpleasant experiences seriously is often neglected in leadership responsibility, he wrote in 2019 in Achtsam und wirksam - Führen aus dem Geist der Jesuiten. Despite all the criticism, however, it should not be overlooked that there are also numerous examples in the church of exemplary fulfilment of leadership responsibility for the benefit of the people entrusted to them.

The effectiveness of leadership essentially depends on attentiveness to the needs of the other person. Leadership is all the more effective and is all the more readily accepted the more the leader listens to the subordinates' deeper desires, potential and specific difficulties and builds on these, which in no way excludes setting tough limits from time to time. A boss should not degrade the people entrusted to him or her to the status of recipients of orders, but should endeavour to encourage their creativity and initiative.

With Paul, the priesthood is not to be understood as a gatekeeper and controller of access to God, but consistently as a service: "Not masters of your faith, but servants of your joy" (2 Cor 1:24). According to Romano Guardini, Jesus himself is the model for such a use of power as a service to joy: "God himself enters the world and becomes man. Jesus' entire existence is the translation of power in humility," he says in his central work The Power on page 122 of the 2019 edition. The courage to serve is "the redemptive answer to the problem of power that Christianity

exists", writes Guardini on page 120 of the same work.

The subsidiary unity of the tension between power and service requires a balanced concept of power as a constitutive component of all human relationships, which, however, is always in danger of leading to relationships of dependency. This danger by no means only affects those in positions of power, but also all those who think they can get rid of their often uncomfortable personal responsibility in favour of a blind obedience mentality. Who hasn't experienced the temptation to delegate responsibility to the boss, the state, the church or the circumstances? There is often strong inner resistance to the effort of thinking for oneself and acting autonomously. The ability to do this requires self-conquest and education. Without a mentality of being a follower, the danger of abusing power would be much lower. As in the fairy tale of the emperor's new clothes, often nobody dares to say that the emperor is "naked". Petra Morsbach describes this phenomenon of the abuse of power made possible by silence and a lack of resistance as the "elephant in the room". Controlling power requires the civil courage of independent people with a strong character. This is also an educational task.

A responsible approach to power in the church requires a separation of powers and checks and balances as a means of preventing a power from becoming independent, sacralising itself and thus immunising itself against criticism. It requires transparent procedures and decision-making processes as well as a culture of subsidiary promotion of freedom. Equally important, however, is the courage to take genuine leadership responsibility in the church, politics and society in order to enable collective action as a response to the complex challenges of the present. Criticising abuse should not displace the realisation that taking responsibility in the sense of communicative power is indispensable, especially in times of crisis. Ultimately, the idea of responsibility is inconceivable without a positive concept of power. However, only those who are aware of its ambivalences and endeavour to exercise it in a humane and appropriate manner on a daily basis will succeed in using it responsibly.