What can interest theologians about literature? Why does a scientifically trained mind that reflects on religion need poetry? Let's take a look at an initial answer, written down in the middle of the 20th century: the "word of poetry" makes "the thing, the experience, the fate more dense and clearer at the same time". More concretely: It is precisely in the poem that "a gaze of a special kind is directed at existence", "more deeply urgent than the gaze of everyday life, and more vivid than that of the philosopher". It is unmistakable that "the words in which what is seen is revealed have greater power than those of everyday life and are more original than the language of the intellectual".

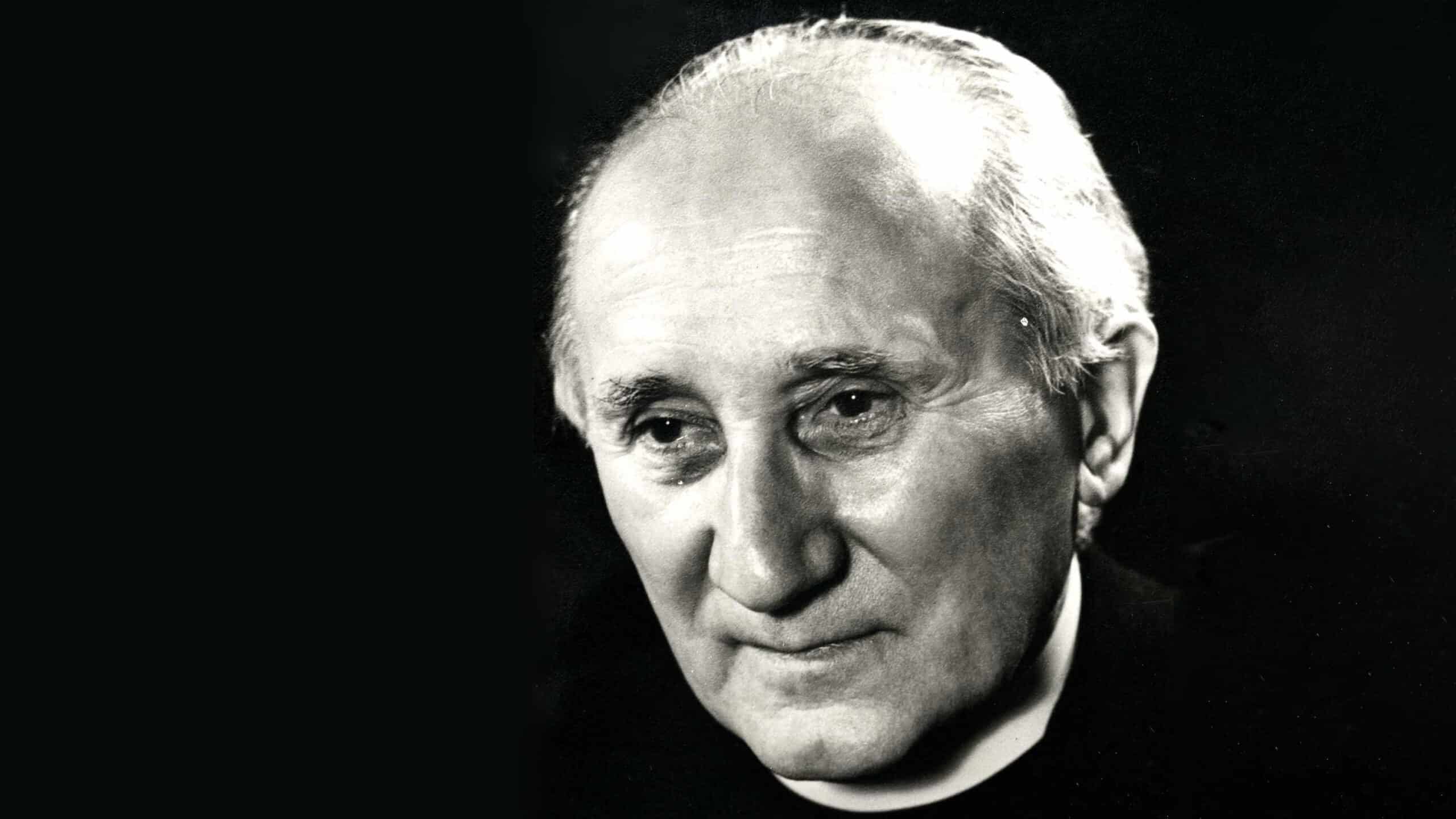

The author of these lines, Romano Guardini (1885-1968), is considered one of the greatest theological literary interpreters of the 20th century. He had always combined his vocation as a theologian with a penchant for literature, the arts and philosophy: he was an avid reader from childhood. And if his career choice had been made freely and independently of family expectations and socio-political conditions, he would have "probably studied philology and literature", as he wrote in his autobiographical notes.

Let's take a closer look.

- What significance did poetry actually have for Guardini's life and thinking?

- What hermeneutical significance do Guardini's literary interpretations have for theology as a whole and for the dialogue between theology and literature in particular?

- What milestones did he set in this area?

Let us first look at the situation that Guardini found himself in. How was poetry dealt with from a theological perspective up until the middle of the 20th century and, in some cases, far beyond? To put it more precisely: what hermeneutical significance did literature have for theological endeavours? After all, theologians have always read literature in their private lives. But did they make this private reading fruitful for their theological thinking and writing?

Theology and literature in the pre-modern era

First of all, it is important to realise this: Speaking of two independent, clearly differentiated areas of religion on the one hand and literature on the other is anything but self-evident in the European context. With all due caution - and in awareness of the need for internal differentiation - it can be stated that in the context of the pre-modern era, these areas belonged together or were at least closely related to one another. The detachment of culture from the sphere of Christianity took place in progressive stages of development from the 17th century onwards. It was only now that an 'autonomous' understanding of art and literature emerged, which finally became established with the increasing secularisation from the beginning of the 19th century.

Autonomy, of course, does not mean a lack of relationship. On the contrary, it was only after the unity of popular religion(s) and literary creation had been broken that independent, productive and challenging analyses of the Christian tradition in the field of literature became possible. Whereas previously it was primarily a matter of embellishing, illustrating and confirming religious precepts, there is now a tense relationship that is enriching for both sides: for theology, because it can constantly scrutinise itself and develop further through the reflections and provocations of literature; for literature, because it can repeatedly make discussions with traditional religions, religious experiences and theological reflections aesthetically fruitful.

The first theoretical reflection on this newly emerging tension in the German-speaking world took place in the context of reflection on Christian literature, a term that only now - as an explicit demarcation against secular literature - became meaningful. The term first appeared with the Romantic writer August Wilhelm Schlegel (1767-1845), who, together with Josef von Eichendorff, Clemens Brentano, Annette von Droste-Hülshoff and others, endeavoured - in vain - to restore the broken unity of literature and religion. The talk of Christian literature was thus a direct reaction to secularisation and initially had a preservative, quite understandably conservative, basic trait.

But why did people continue to be interested in explicitly 'Christian' literature into the 1960s? A look at the very different intentions and works, styles and formal requirements as well as writers labelled in this way reveals this: The return to 'Christian' literature consciously rejected modernism. As a reaction to its crises and upheavals, a return to the worldviews of a closed view of reality was propagated: religious, Christian, confessional.

So how was poetry dealt with theologically before Guardini and even after him? Looking back, three basic lines emerge.

1. theological interpretation of literature focussed almost exclusively on the familiar field of Christian literature, which functioned neither as a challenging partner in terms of form or content, but rather as ideological self-affirmation and aesthetic enrichment in a familiar form.

2) In terms of form and content, this poetry remained committed to the world of the pre-modern era, adhering to a closed Christian world view before all secularisation. This includes the refusal to recognise contemporary developments and upheavals as well as the concentration on long-established genres and stylistic decisions.

3 The focus was less on the literary work itself and more on the stylised and idealised person of the Christian poet or the spirit that shaped his work. Philologically analysing interpretations of the text remained the exception.

What of this did Romano Guardini adopt, and where did he seek and develop his own new approaches?

Comprehensive interpretation of world literature

Against this background, the scope, style and range of Guardini's literary interpretations are viewed with amazement and respect. In addition to smaller works on Dante, Goethe, Shakespeare, Hopkins, Wilhelm Raabe or Mörike, for example, three major monographs on outstanding poets of world literature and their works were written over the years, usually in several preliminary stages: on Dostoyevsky (1932), Hölderlin (1939) and finally on Rilke (1953). A key point to understand: Guardini did not follow a programme planned long in advance in his interpretations of literature. He responded to suggestions and enquiries that came to him from outside. A systematic or prefabricated programme is not to be expected from him.

Let's take a closer look: Why does Gardini take a theological approach to literature that goes beyond a fundamental enthusiasm for poetry in general? In the preface to his interpretation of Wilhelm Raabe's novel Stopfkuchen, published in 1932, he explicitly states that he "does not want to talk about the book in general terms, but really interpret it".

We ask three questions.

- Firstly: 'Really interpret'? What does this mean for Guardini as a theologian and philosopher?

- Secondly, what fascinates him about the authors he analyses?

- And finally: How does he try to open up the intellectual and literary worlds presented to his readers?

The concrete impetus to devote himself intensively to poetry came from the philosopher Max Scheler (1874-1928). When Guardini was appointed to the Chair of Philosophy of Religion and Catholic Worldview in Berlin in 1923, he initially did not really know how and for whom he should design his lecture programme there. A Catholic from the provinces in the seething, sophisticated, frivolous Berlin of the 1920s?

In a conversation that was "very momentous" for him, Scheler - the renowned, revered philosopher who was eleven years his senior - advised him: "You would have to do what lies in the word Weltanschauung: look at the world, things, people, works, but as a responsible Christian, and say what you see on a scientific level," Romano Guardini recorded the conversation in retrospect. And then Scheler gave specific advice: "Why don't you examine Dostoyevsky's novels, for example, and comment on them from your Christian point of view in order to shed light on the work under consideration on the one hand and on the starting point itself on the other." Guardini - whose literary interpretations quickly reached a wide audience - would follow the advice and always remember his colleague with gratitude.

Witnesses to life after the end of the modern era

Of course, this was only the external reason for his turn to the interpretation of literature. Guardini's future direction was primarily illuminated by two inner bundles of motifs. In his epoch-making work The End of Modernity (1950), he formulated his fundamental criticism - which had grown over decades - of the rationalist-technological expediency of modernity, which in his view had not coincidentally led to the catastrophes of the world wars and the Nazi dictatorship. In doing so, he remained - as countless of his companions testify - torn between a nostalgic longing for the lost and a defiant willingness to face the new challenges of his present.

and future.

Throughout his entire oeuvre, he is centrally concerned with profiling the spiritual counterforce of Christianity as a real alternative to this contemporary trend. By referring to the great poetic-religious thinkers of history, he creates such a counter-profile. For which Christianity did he want to strengthen as a spiritual counterforce? Not the rigid system of pre-modern theology, which for him was associated with the concept of neo-Scholasticism; not the hierarchical, fixed form of Roman rule and the liturgical routine, which in his eyes was petrified. For and with Guardini, there is no remaining in the pre-modern era, however appealing the idea of perseverance may be. He was convinced that Christianity had to prove itself in the confrontation with modernity, that it had to be re-moulded and conceptualised differently.

And this is precisely where poetry, 'beautiful' literature, comes into play. Guardini needed witnesses to demonstrate a lively and boundary-breaking spirituality, to demonstrate the deep power of genuine spirituality. He wanted them to embody both at the same time: the crisis of modernity, but also the possibility of a renewed return to Christianity beyond the suffering of this crisis.

In his search for such figures of orientation, he came across philosophers on the one hand, but also great writers of world literary significance (in fact, exclusively men) whose works gripped him with their force and greatness. It is therefore hardly surprising that, unlike the protagonists of theological literary interpretation before him, Romano Guardini was not primarily interested in calling upon explicitly Christian witnesses who only confirmed what he had previously believed in a particularly impressive form. Rather, he associates the writers he calls upon in the category of seers. He recognises in them the gift of visionary prophets. So what makes his writers religious witnesses? The ability to see and name the truth more clairvoyantly, more deeply and more clearly than others. He hoped to find in them what he could not find in the theology of his time.

Writers as prophetic seers

Let us look at examples: Guardini introduces Hölderlin, for example. Hölderlin's work does not - as with others - emerge solely from the artist's powers, which are determined by the "authenticity of experience, the purity of the eye, the power of moulding and precision". In Hölderlin's case, what is special comes "from the vision and shock of the seer". The origin of his work "lies a whole order further inwards or upwards", so that it is "in the service of a call", which to evade would mean "resisting a power that transcends individual being and will". In Hölderlin's work, the reader therefore not only encounters the literary voice of a man of genius, but rather a divine voice becomes audible in the voice of this seer and caller.

Guardini thus describes the poet as a true prophet and can thus consistently conclude that these poems are characterised by the "character of revelation", even if he adds a qualification: "the word taken in a general sense" in relation to phenomena in which something emerges that "is not primarily and simply given, but comes to be given through them as something underlying, hidden, actual". According to Guardini, Hölderlin was a "seer called to religious service", in "whose inner being the touch occurs, the vision arises and the mission is given to the message".

What Guardini explicitly states about Hölderlin fundamentally characterises his choice of authors and interpretation of texts. With Dostoyevsky, he is attracted by the possibility of revealing the religious emotion of the outstanding characters in his novels. These literary characters were "exposed to fate and religious powers in a special way". Guardini is interested in seekers, disturbed and disturbing border crossers, people at risk within themselves and torn between different life plans and expectations. For him, they are soulmate witnesses to the end of the modern age. A new spirituality, a new sustainable world view must prove itself on them, with them.

This is why he turned to Rilke, "perhaps the most differentiated German poet of the end of the modern era", according to Guardini's characterisation. Guardini struggled with no other work as much as with Rilke's. Nowhere else did he vacillate so much between fascination and rejection. Rilke - like Hölderlin - was "medially inclined" and also saw himself "in the position of the seer", "convinced to speak a message that was dictated to him from an origin that could probably not be called anything other than religious". According to Guardini, Rilke saw himself as a "prophet who is an organ; who passes on what the divine voice speaks through him, and who himself, as a human being, faces his own word in the attitude of the listener and slow penetrator". The fact that this religious aspect also explicitly takes on forms and statements that are "in contradiction to Christianity" is part of the provocation of this design.

Contemporary literature? A fade-out

Guardini does not seek and find confirmation of his own understanding of Christianity here, but rather a critical examination of the person and work of these seers for the purpose of struggling for genuine and sustainable truth. What takes place in Rilke's work are "combustion processes that illuminate hidden things, release vibrations, awaken resonances - but in which something also disintegrates that belongs to the structure, one might say to the honour of language", says Guardini in an ultimately distancing epilogue to his Rilke book, which was created in a slow and arduous process. Although Rilke "stands not only for himself, but for our entire time", anyone "who wants to learn to speak poetically must be warned against Rilke", as he "dissolves personality".

Hans Urs von Balthasar wrote in 1970 that this study was nothing more than "a swan song", a struggle that ultimately testified to a failure of rapprochement. No wonder Guardini interpreted poetry "no further after Rilke", Hans Urs von Balthasar later commented. Guardini could not avoid confronting poetry with the question of truth and critically evaluating it from there. In the end, the ambivalence of fascination and distance, of temptation to read and simultaneous warning, remains, especially with regard to Guardini's reading of Rilke.

Hölderlin, Dostoyevsky, Rilke: there is another link between these three writers and others whose work Guardini read and interpreted. It is striking that he himself knew numerous writers of his time personally. "I found inspiring friends," he recalls of his student days in Munich, for example, "among writers". That will remain so. He was friends with many authors, some of whom he invited to read from his works, some of whom he exchanged letters with, and many others whose works he is known to have read.

At no point, however, did he interpret works of contemporary literature. A significant and certainly deliberately strategic reticence! His engagement with literature obviously presupposed the presentation of completed life's work. He did not want his interpretations to be clouded by personal acquaintance or friendly obligation. Texts and their spiritual worlds interested Guardini theologically and conceptually, not writers as witnesses of the present.

"... in as close contact as possible with the texts themselves ..."

Just how much Guardini was interested in a very personal appropriation and spiritual interpretation of literary drafts is clear from the method he chose. "I endeavoured to come into the closest possible contact with the texts themselves," he wrote in the foreword to the 1939 Hölderlin book, which was not fundamentally about an examination of literature in a scholarly sense, but consciously about his individual reading, guided by "philosophical intentions". He later asserted that he had "no intention of intervening in literary studies as such".

He almost flirts with the fact that he deliberately did not even read key works of secondary philological literature. "I deliberately dispensed with the relevant specialised knowledge, [...] I went by instinct." Guardini claimed the right to limit the specialised studies he took note of "to the minimum necessary to be informed about the facts". He wrote in his autobiographical notes that he had acquired a method "to penetrate from the exact interpretation of the text to the whole of the thought and the personality" and in doing so "to free the Christian meanings from all the dilutions and mixtures" into which "modern relativism had brought them". This, the fine drawing of a Christianity fit for the future, is what he is concerned with in the literary interpretations.

As appealing as the basic trait of a close examination of the original texts themselves may seem, as fascinating as his struggle for statement, reference and deeper truth may be - this hermeneutic approach to literary texts has far-reaching consequences. There is no question that Guardini's comments on poetry are still interpretations worth reading. However, their scholarly relevance has always been - and remains - limited. Throughout his life, he let his ability to supervise doctoral students go to waste. He was not interested in forming a school. No one continued or developed his theological and literary work independently.

Guardini's theological interpretations of secular literature thus prove to be milestones in a theological reception of literature that takes literature as seriously as possible in the sense of incorporating it as closely as possible into the theological-spiritual style and context. He was interested in a genuine "encounter", in "looking from the one to the other", in approaches that ultimately "want to be neither literary studies nor theology", as Guardini himself put it in retrospect. However, he underestimated how much he always remained a theologian, especially as an interpreter of literature. Poets as seers; poetic works as testimonies in the service of the divine call, indeed: as works of revelation - here literature is radically interpreted theologically.

It is possible that Guardini realised the limits of his approach more and more clearly as he grew older. In the epilogue to his late interpretations of Mörike entitled Bemerkungen über Sinn und Weise des Interpretierens from 1957, he relativises the claim he had previously formulated himself that literature could have something prophetic. He now criticises Rilke for having seen himself as a prophet, because poetry is "infinitely different" from "what speaks in the real prophet", without Guardini explaining the difference he is admonishing in more detail. Here he only concedes to the poets that there is something more that speaks from them, something more to determine than "existence itself".

In general: after the major work on Rilke, which was only completed with great difficulty, the poets clearly lost their appeal for Guardini. Apart from the smaller works on Mörike, he ended his literary interpretations. "The line from Hölderlin to Rilke had obviously led to a dead end," is Alfons Knoll's judgement in a comprehensive monograph on the subject. There may be two reasons for this. Firstly, it is obvious: The closer the literature he examines comes to his present, the more critical Guardini's judgement becomes. It has already been emphasised that he does not focus on contemporary literature. And the study of Rilke increasingly became a distancing exercise.

Why? The second reason for Guardini's waning interest in the literati may have been his growing realisation that the poets could provide him with one thing above all: impressive testimony to the end of the modern era, which he himself had diagnosed. However, they could not provide the second thing that was central to him: Testimony to a return to the world of Christianity under new auspices. For Guardini, poetry was therefore possibly two things: a great discovery, but at the same time perhaps also ultimately a great disappointment. These considerations challenge us to conduct follow-up analyses.

Questions from today's perspective

Later drafts of the theological-literary dialogue will take a critical approach to Guardini's self-retractions and ask whether the independence of the aesthetic field is not sacrificed in his interpretations in the theological field. The American literary scholar Theodore Ziolkowski - as an example - praises Guardini's literary interpretation for its "sober combination of careful textual analysis and Christian hermeneutics", but uses Guardini's interpretation of Mörike to prove that he imposes his own faith, his own expectation" on the text at a "decisive point [...] and finds the religious where he was looking for it.

And a second question arises with regard to the deliberately personalised language. The German scholar Wolfgang Frühwald summarises the results of his research with regard to Guardini's literary interpretations: they were "very much of their time [...] and thus (partially) became unreadable". With his "existential-philosophical vocabulary", Guardini "accepted the risk of quickly becoming outdated".

Despite all the possible questions, which are in themselves questionable from today's perspective, Guardini's achievements and limitations can be summarised in the field of theological interpretations of literature.

1) In contrast to the prevailing endeavours in the examination of Christian literature up to his time, Guardini is directly concerned with the texts and less with the biographically illuminated or exaggeratedly typified authors. He interprets literary works and integrates the aesthetic interpretations into his previously theologically characterised world view. To this end, he only makes peripheral use of biographical, cultural-contextual or philological secondary literature. He is concerned with his own authentic interpretations.

2 The attraction of interpreted literature, as Hans Urs von Balthasar later wrote about his academic teacher Guardini, lies in the "open places where fundamental questions break open, windows burst open, lights flash through, places where the Eros of questioning ascends up stairs, but does not refuse to radiate downwards in any way whatsoever".

3. literature provides the theologian with language, authenticity and topicality that he does not find among his contemporary theologian colleagues. He hears a prophetic power in the great poets, which of course is not understood in the sense of biblical prophecy.

4 However, he is not only concerned with poetry because it serves him as a kind of language school and stylistics or sensitises him to the developments of his present. Guardini also engaged in "theological literary criticism" by "scrutinising literature for its ultimate attitude". For him, theological guidelines ultimately become the yardstick for literary judgement.

5 Guardini clearly recognises the epochal change that he himself experiences and witnesses. The religiously determined pre-modern age is increasingly being replaced by a modern age that can not only be defined philosophically, economically and politically, but also increasingly determines people's everyday lives. This change presents Christianity with new challenges, which it wants to face with its theological concepts. Despite all the longing for past security, Guardini's literary theology dares to take the step into an open search.

Guardini himself could not have foreseen that this search would ultimately take place in other paradigms. The new discipline of theology and literature - inspired above all by Paul Tillich's theology of culture - would develop from the 1970s onwards in the paradigm of dialogue. Poetry and religion will be linked correlatively, at eye level, in mutual respect and challenge. Guardini's interpretations of literature paved the way for this paradigm. Guardini himself did not follow this path.