Luke is widely regarded as the first Christian historian, and the Acts of the Apostles accordingly as a historiographical work. This is, of course, open to debate - and the exegetical literature bears witness to this. the debates that were held about it.

For example, we should ask whether there are not also elements of historiography in Luke's predecessor works - especially in the Gospel of Mark - and we are sure to find them. So is Luke really the first?

Furthermore, is what Luke offers really historical writing, or is it not primarily characterised by his intention to preach? Is Luke not rather a writer of edification, as Ernst Haenchen in particular emphasised in his commentary on the Acts of the Apostles? This cannot be completely dismissed either.

For an initial orientation, let us ask what characterises historiography. The ancient historian Joachim Molthagen wants to speak of a work of history "if, based on careful endeavours to gain reliable knowledge, it presents a larger context of past events, combining the details into a larger whole and offering an understanding interpretation whose particular accents (...) result from the respective author's view of the matter presented and from his understanding of history."

The Acts of the Apostles as a historical work

These characteristics can certainly be observed in the Acts of the Apostles. The claim that Luke formulates in the prooemium of the Gospel of Luke already identifies him as a writer who carefully endeavours to obtain reliable knowledge. In Luke 1:1-4, he presents himself as a meticulous worker who has made a thorough study of the sources and now presents everything available to him as a meaningful, coherent and reliable draft, a diēgēsis, which is rendered as a "narrative" in the standardised translation, but would be better described as a historical monograph.

Luke states that the aim of his account is to give his addressees - specifically addressed in the person of Theophilus - grounding again and to demonstrate the reliability of what they have already been taught.

This first proemium is followed by the proemium of his second volume (Acts 1:1). Although Luke no longer explicitly refers to his study of sources here, it can be assumed that he also used sources for this volume, even if they can hardly be reconstructed. Thus the claim in Luke 1:1-4 can certainly also be applied to the second volume.

On this basis, Luke tells the story of the spread of the message of Christ from Jerusalem, via Judea and Samaria "to the ends of the earth" (Acts 1:8). Although the book of Acts does not really end "at the ends of the earth", it does at least end in Rome, where Paul's proclamation at the end of the book opens up a perspective into the future.

In many aspects, Luke works in a way that is typical of historical works. For example, right at the beginning of Luke's Gospel, he places the events he is recounting in the context of world history by naming the rulers at whose time all this happened: in addition to the Roman emperors Augustus and Tiberius and their governors, these are above all the Judean client kings Herod and his sons (Luke 1:5; 2:1-2; 3:1-2).

Luke also weaves the names of corresponding rulers and representatives of Roman state power into the Acts of the Apostles at appropriate points: in Acts 18:2, for example, he mentions the edict of Emperor Claudius from the year 49 AD, which led to the expulsion of the Jews from Rome and which the Roman historian Suetonius also mentions in his Vita of Emperor Claudius (Claud 25:4). The proconsul Gallio in Corinth is also mentioned in Acts 18 (Acts 18:12). The encounter between Paul and Gallio in Corinth described here - assuming that it can be regarded as historically plausible - has developed into a fixed point in Paul's chronology.

Luke links all the events narrated into a coherent whole. At the beginning of his work, he sets out the perspective and repeatedly provides readers with interpretative aids in the course of his work in order to correctly understand what is being narrated. It therefore makes perfect sense to regard Luke's work as a work of history. But of course it has its own special features. These become apparent when we compare the Acts of the Apostles with other ancient historical works.

Ancient historical works between fact and fiction

Firstly, a clarification: even if the Acts of the Apostles is to be categorised as a historical work, this does not mean that everything that is told in Acts is to be assigned the status of events that actually happened. Even in antiquity, people were aware that every historian - and we are probably less likely to be able to assume that this is the case with female historians - is also creatively active, selecting, arranging, explaining and giving meaning to the material.

One example of this is the orator, writer and satirist Lucian of Samosata. In the second century AD - somewhat later than Luke - he wrote his own work on how history should be written. In it, he begins by distinguishing historiography from poetry. On the one hand, this shows that historiography must be distinguished from poetry, but on the other hand it also shows how close the two areas are.

Lucian continues: A historian must indeed carefully collect the historical material, must scrutinise it and either convince himself of its reliability or rely on reliable eyewitnesses, and from this he should produce a rough draft that forms a coherent whole, but need not yet satisfy the demands of beauty. Only then should he arrange the material and "strive for the beauty of the depiction and lend colour, form and rhythm to the language". In doing so, he should present in a balanced way, but concentrate on what is important, maintain moderation, ensure variety, organise well and present as clearly as possible. Unimportant things should only be hinted at or even omitted, and he should always come back to the central theme.

It is significant that Lucian uses the image of a mirror for the historian's work, which throws an image sharply back. This makes it clear that it is an image that is created by the historian by organising and presenting the material. Thus, "the historiographers are not concerned with the what, but with the how."

The extent to which historiography also belongs to literature and contains both non-fictional and fictional elements is shown by the Alexandrian rhetor Ailios Theon (second half of the 1st century AD) in his preliminary exercises (Progymnasmata) for the training of rhetors. Here he defines the technical terms diēgēma and diēgēsis as "an unfolding account of things that have happened or as if they had happened."

There is therefore something of a "fictionality contract" between the historians and their addressees, as Umberto Eco called it in his text Six Walks in the Fictional Woods. The author leads the addressees into a past that only exists in the realm of the imagination - and the addressees agree to believe in it.

Plutarch (ca. 45-125 AD) summarises this agreement in his biography of the legendary Athenian king Theseus as follows: "May it therefore be given to us, through reason, to polish the legendary narrative so that it obeys and takes on the appearance of history. However, where it stubbornly refuses to make itself credible and refuses to accept the admixture of probability, we would ask for willing listeners/readers and (for) those who accept the science of antiquity in a benevolent spirit."

The extent to which ancient readers followed their authors and accepted their depictions - or: the extent to which they actually saw through the game of fictionality - may well have varied. But let us note that what has long been taken for granted in modern historiography - namely that no historical account simply reproduces objectively how things really were, but that every account must select from a certain perspective and find an order, that it links the events into meaningful contexts, thereby interpreting and not only reconstructing history, but also constructing it - can already be found hinted at and even reflected in ancient authors.

Despite all this: striving for accuracy

Nevertheless, ancient historiography began with the pursuit of accuracy, in contrast to poetry, which was allowed to focus more on beauty. Thus Lucian describes it as one of the historian's tasks to "report how an event took place". However, he convincingly argues that this is not possible if one is dependent on the protagonists depicted or speculates on the applause of the contemporary audience. A historian should therefore be "fearless, incorruptible, independent, a friend of frank speech and truth" and present his material without regard for the powerful or the audience.

This striving for accuracy can be found from the very beginning of Greek historiography. Even Herodotus (ca. 484/3-425 BC), who is described by Cicero as the "father of historiography" (pater historiae), wanted to offer an "exposition of his research" in his work, as he says in the prooemium. And so he endeavours to provide reliable knowledge, distinguishes between reliable and questionable information in his accounts and also researches the causes of the events. For his account of the Persian Wars, he still had to largely dispense with written sources because no such sources existed. He therefore had to rely on sources, some of whom were eye and ear witnesses, but some of whom had no first-hand knowledge of the events.

With regard to such guarantors, he describes his task as follows: "But it is my duty to report everything I hear, and certainly not to believe everything that is reported." He therefore sometimes looked for a second witness to authenticate an event that sounded all too improbable. For example, he based the story that the singer Arion was rescued by dolphins after a shipwreck and came ashore safe and sound on the testimony of both the Corinthians and the Lezbians. However, where something seems all too questionable or even contradictory, he often leaves it up to the reader to judge. It is not for nothing that Cicero attests that he also provides countless fabulous stories (innumerabiles fabulae).

Thucydides (ca. 460/454 - after 400 BC) emphasises even more strongly the thoroughness of his research on his major topic, the Peloponnesian War: "For writing down the actual events of the war, however, I did not consider the questioning of every source that happened to present itself to be the right basis, nor my own assessment, but rather the investigation with all possible accuracy (akribeia) of every detail, both of the events that I myself was present at and of those reported to me by others. As a rule, this proved to be difficult because the eyewitnesses did not report the same things about the same events, but rather according to their sympathy for one side or the other or their "memory".

Polybius (ca. 200-120 BC) also endeavoured to obtain reliable knowledge and even revealed some of the sources to which he had access in Roman archives. For him, too, it was a matter of researching and presenting the truth.

This shows that the work of Herodotus, but above all the historiography of Thucydides and Polybius, is characterised by precise and methodically reflected research into the events. Both are sensitised to statements made by sources and evaluate them critically. What is narrated is attributed to the actions of people, but not explained metaphysically, for example through the intervention of deities. The events are fuelled by human motives and driving forces such as greed, fear, ambition or other diagnosed human pathologies. In this way, causalities can be established and a distinction can be made, for example, between the beginnings of an event, its actual causes and the pretexts put forward.

This is related to the fact that both of them think about the stylistic device of direct speeches. They repeatedly incorporate speeches at key points in their portrayal. They serve to mirror the events by drawing on actual speeches made in these situations. However, because no transcripts or recordings of these speeches exist, this is where the historian's view comes into play, who can use these speeches to shed light on the situation and work out causalities and deeper causes.

Under no circumstances, however, and both Thucydides and Polybius emphasise this, should speeches be used purely as decoration. On the contrary: rhetorical ornamentation, showmanship and amusement are deliberately avoided. Instead, the two authors rely on the strenuous co-operation of the readers. As a lasting reward for their efforts, both promise instruction and guidance for their own actions.

Not to forget: the need for entertainment

If reading historical works takes so much effort, it is no wonder that this endeavour is increasingly perceived as an imposition. Dionysius of Halicarnassus (ca. 54 BC to after 7 AD), for example, says quite bluntly that Polybius was one of those historians that nobody could read to the end.

It can be observed that other ways of writing history were found in the Hellenistic period. On the one hand, individual persons and their biographies were increasingly placed at the centre, while on the other, syntheses were sought and larger units were taken into consideration. On the one hand, historians organise such large units by structuring them externally according to books. On the other hand, they find an internal structure according to geographical aspects. While Thucydides and Polybius attempted to structure their work by placing it under a guiding idea, historians from the Hellenistic period onwards chose the more descriptive geography as a structuring principle.

When different parts of the world come into view in this way, it is only a small step to reporting marvellous events from these parts of the world - and this can already be observed in Herodotus. More marvellous stories could then be linked to the places visited, as Theopomp (ca. 378/377-323/300 BC) included in his Book VIII about the Macedonian king Philip a compilation of thaumasia, astonishing events from various parts of the world, and referred, for example, to the view of Persian magicians that people were immortal and would always come back to life, or that the universe would always remain the same in a circular motion. This trend of incorporating such astonishing events into historical works continues. They are offered to readers as a reward for reading.

In addition, there have been specialised stories with a strong biographical focus since early Hellenistic times. The biographical depictions of Alexander the Great and the various versions of the Alexander romance, in which a number of miraculous episodes were incorporated, including the apotheosis of Alexander, set the course for further development.

Such biographical portrayals of special people invite us to dramatise the lives of these protagonists. Cicero justifies this by arguing that rhetors are allowed to lie in historical works so that they can express certain things or aspects more clearly. With this in mind, in his letter to Lucceius, Cicero encourages the latter to embellish his account of the consulship a little more than the truth would allow. Because: epistula ... non erubescit - paper does not blush, in other words: paper is patient.

In general, historiography was increasingly equipped with elements of tragedy. This gave historians the opportunity to be somewhat freer with the truth for the sake of the audience and to clarify the overall meaning. These possibilities seem to have been utilised above all in Roman historiography, as it is well known that there were hardly any written sources about early history and long stretches of the Roman Republic. It was therefore necessary to form a coherent story from the few documented historical memories. To do this, the historians - despite the strict form of the annals they chose - had to invent dates and construct contexts of the early period.

They were just as aware of this freedom in dealing with their material as their reading public. The Greek historian Ephorus of Cyme (ca. 400-330 BC) wrote: "We consider those who report the events of our time very precisely to be highly trustworthy, and those who write about ancient times in this way to be highly untrustworthy, because we must assume that it is unlikely that all the deeds and most of the speeches could have been remembered for so long."

Livy also makes it clear in the praefatio of his History of Rome: "What is more embellished with poetic tales before the foundation of the city or the plan for its foundation than is handed down in unadulterated testimonies of events, I would neither like to present as correct nor reject. It is a credit to the old times that they glorified the beginning of the city by mixing the human with the divine."

Nevertheless, Livy wrote no less than five books about these beginnings of the city. In doing so, he often emphasises the uncertainty of this or that episode and is not sparing in his criticism of his predecessors. Nevertheless, he is involved in a historical account that supplements the little that is reliably documented in sources with fiction and thus does not so much research the past, as would be the case in the modern sense, but rather creates a new image of the past.

Increasingly, fictional elements were included in historical works, which is precisely what was criticised in the case of the predecessors. In contrast, attempts were made to present their own accounts as credible by means of proper authentication devices, to the extent that not only events were invented, but also the corresponding sources. The Roman rhetoric teacher Quintilian (ca. 35-96 AD) came to the following conclusion: "Historiography is very close to poetry, is in a certain sense a poem in unbound form and aims to tell, not to prove."

All of this is intended to reach readers. According to Lucian, readers "become attentive of their own accord as soon as the author demonstrates that he wants to deal with subjects that are significant and important, that concern them and are of benefit to them".

Borrowing from the historical works of the Old Testament

It has been shown: The spectrum of ancient historiography is broad, and it naturally changes over time. The Acts of the Apostles can also be categorised within this broad spectrum of ancient historiography.

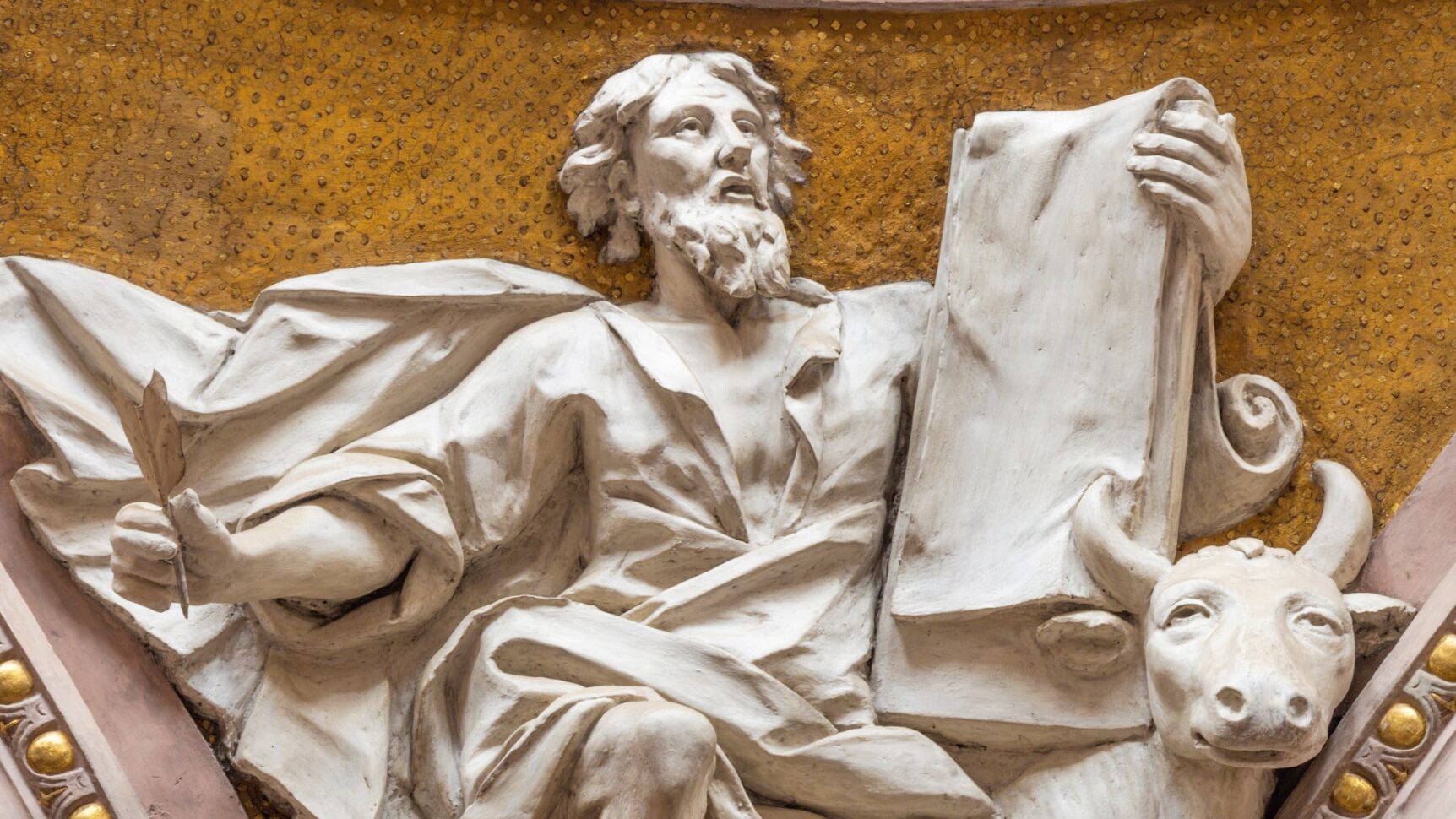

At the same time, it cannot be overlooked that the Acts of the Apostles also goes its own way. Above all, it borrows from the historical works of the Old/First Testament, which have not yet been mentioned. In his books, Luke proves to be a profound connoisseur of the Jewish Holy Scriptures. In the Acts of the Apostles, this is particularly evident in the speeches of the apostles in Jerusalem or in the speeches of Paul, with which he proclaims his message in the synagogues.

This background must be taken into account if we want to understand how Luke conceived his second volume, because the historical works of the Old/First Testament and in particular the Deuteronomistic historical work tell history as the history of God with his people. It is about presenting history in a dialogue with faith in God; it is about understanding how everything came about as it did, including and especially the great catastrophes such as the conquest and destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians, the destruction of the temple and the deportation of the upper class to Babylon. It is about God's actions in history and Israel's and Judah's responses to them, it is about human failure in the face of God's saving action and the consequences that follow, some of which are as catastrophic as the Babylonian exile, including the end of Davidic kingship and so on.

Once again: The Acts of the Apostles as a historical work

Luke presents his second volume to his readers as a continuation of his first volume, in which, as he says at the beginning, he had reported "all that Jesus did and taught from the beginning until the day he was taken up to heaven" (Acts 1:1f). Although this continuation is not a history of the early church in a comprehensive sense, the book shows how the message of Jesus, the Christ, spreads, starting from Jerusalem, via Judea, Samaria, to the "borders of the earth" (1:8), and how Jewish people and people who do not come from the Jewish tradition react to this message, positively or negatively, right up to the final chapter, which does not exactly end at the borders of the earth, but in the centre of the Roman world empire, in Rome. This makes Luke, with his subject matter and the way he presents it, the first person in Greco-Roman antiquity to depict a religious movement in the form of a historical account.

However, this type of depiction also makes it clear how much Luke has already made a selection. His story is set between Jerusalem and Rome. What does not lie between these two poles is not in view.

This selection is initially due to Luke's conviction that what he is narrating is important for his readers. This links him with Herodotus, Thucydides and Polybius and their conviction that their material is of outstanding importance for their readers. To emphasise the importance of what he is telling, Luke has Peter, an important protagonist of the opening chapters, say to the high council: "And there is salvation in no one else. For there is no other name under heaven given among men by which we must be saved." (Acts 4:12) For his own time, the time between Jesus' earthly ministry and his promised return (Acts 1:11), the spread of the message of Christ is the most important topic.

This spread of the message of Christ, starting from Jerusalem via Judea and Samaria to Rome, also becomes the organisational and structural scheme for the story told. Luke fits the traditions, some of which already existed, into this structure and thus establishes an order. According to Daniel Marguerat, who has been researching the Acts of the Apostles for years and published his extensive commentary on Acts in 2022, Luke becomes a historian precisely because he puts the disorganised facts into an order that turns them into a founding story of early Christianity.

In his account, Luke places particular emphasis on the emergence of the communities of believers in Christ, especially in the first chapters and on the basis of the church in Jerusalem. Particularly in the summaries, he paints an impressive picture of this early Jerusalem church, of its community life and the community of goods, of the powerful testimony of the apostles, including their numerous miracles, and of the work of the power of the Spirit, through which more and more people were added to the community every day. This community is shown as being both under the grace of God and in the highest esteem among the people, so that the picture of a golden and at the same time standardising early period emerges.

In contrast, the Acts of the Apostles ends with Paul's preaching in Rome and draws a thoroughly mixed conclusion. For us today, the harsh words towards the Jewish people, whose behaviour is interpreted with the help of the command to harden Isaiah 6:9f, are extremely painful to see. But despite all this, Luke has not yet spoken the last word on the subject, and the perspective at the end is open.

The conclusion of Acts shows Paul as a persistent proclaimer of the "kingdom of God" and the "teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ" to "all who came to him" (28:30f) - and he thus hands over the baton to the readers, who are invited to trust this "teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ" and in turn to carry it to the ends of the earth.

Luke tells this story of the spread of the message of Christ in such a way that it becomes clear how much God has a hand in all of this: the programme of the Acts of the Apostles is formulated by the Risen One (1:8), and throughout the work, God himself becomes recognisable as the director of history. The course of history is steered by God through the witnesses of the message of Christ, with the Holy Spirit playing a decisive role, who is bestowed at Pentecost and influences, guides and advances the events as well as the protagonists in the further course and also ensures that certain paths are not taken.

In all of this, the history of Israel appears as an interpretative horizon for the events narrated, so that Jens Schröter can even say that the history of the emerging church is interpreted as a continuation of the history of Israel. This is particularly evident in the speeches of Peter, Stephen and Paul when they each address a Jewish audience. In this way, events from the time of the incipient churches of Christ become recognisable as part of the historical plan of the God of Israel.

It fits in with this historical narrative when the spread of the message of Jesus is accompanied by numerous miraculous events - "signs and wonders" - from the very beginning. Signs and wonders is a pair of concepts that has its place particularly in the Exodus tradition. Obviously something comparable happens in Luke's eyes: there are healings, even the raising of the dead, in the early period performed primarily by Peter, but also (summarised) by the other apostles, in the second part of the book by Paul, who not only heals, casts out demons and raises a dead man (Acts 20:7-12), but even survives the bite of a poisonous viper unscathed (Acts 28:3-6). There are also miraculous deliverances from prison (Peter, John and Paul), the miraculous disappearance and reappearance of the preacher Philip after the baptism of an Ethiopian (Acts 8:26-40), miraculous and always victorious battles with competing magicians (Acts 8:4-13), right up to a shipwreck and the miraculous rescue on the way to Rome (Acts 27).

In this way, the deeds of Jesus' witnesses appear as a continuation of God's powerful actions in the history of Israel and in the work of Jesus. Readers can recognise how God works his mighty deeds through the witnesses of Jesus first among the Jews and then also among people who come from the non-Jewish tradition.

In this way, Luke creates suspense: how often is Paul on the verge of falling victim to an attack - but time and again he is able to escape, is saved by people or angels, until he finally makes it to Rome. In this way, Luke certainly fulfils his readers' need for entertainment. This may also be the reason for such grotesque stories as that of Hananias and Sapphira, on whom a miracle of punishment is performed (Acts 5:1-11), or the story of the revolt of the silversmiths in Ephesus and the huge tumult that the messengers of Jesus only just manage to escape, but during which the crowd shouts for two hours: "Great is Artemis of Ephesus" (Acts 19:23-40). Such elements lend Lucan's account quite novelistic traits; however, as we have seen, such stylistic devices have also characterised Greco-Roman historiography since Hellenistic times.

And the aim of this presentation? All the borrowings from the writings of Israel show how the addressees are in continuity with Israel. At the same time, the salvation given in Jesus Christ is open to all peoples. The history of the spread of the message, which is also a history of conflicts and ruptures - also and especially with members of God's people - shows that this had to happen. The book and the scriptures consulted help us to understand how the faith in Christ arose from Israel, but how this separation came about, even though there is so much in common.

On this basis, the addressees, a not inconsiderable proportion of whom probably came from non-Jewish peoples, can place themselves in history, understand their present with the help of this founding narrative and at the same time develop perspectives. When one's own present is uncertain (cf. Luke 1:4), history can help to clarify identity by giving an account of one's own origins. This is what the Acts of the Apostles attempts to do.