The main sources for Romano Guardini's early personal literary history are the reports on my life written in Mooshausen from 1943 to 1945. Two of them were published in 1984. A third, dated 7 March 1945, is as yet unpublished, but contains the most important and "new" findings for the question at hand.

Guardini's reports about my life

Under the title "Spiritual development and literary work", one first reads fundamental statements about how Romano Guardini categorises art and, with it, literature in the "world". He distinguishes between the "world of the first degree", nature, and the "world of the second degree", culture. In the latter, art and literature are "those forms in which the essence of the world, the essence of things and that of the experiencing human being is given valid expression in the unreal space of the imagination. Thus the work of art in the space of pure contemplation forms a bridge, as it were, to the world that is to come. This, if one may say so, eschatological conception began to assert itself very early on." This refers to the eschatological conception within his view of the world, art and literature. Guardini continues: "Later I also encountered the great masters, especially the French and Russian novels. But I must confess that these great works have always been too demanding for my personal literary needs. I have never been able to socialise with them - the same applies to the greats, such as Dante or Shakespeare - in the so to speak private form of personal reading and absorption. They were too big for me. I could only be in their atmosphere when I became active myself, as happened in the various works on Dante, Dostoyevsky and Hölderlin." Guardini concludes this biographical development with the clear self-recognition: "When I had reached this point, I was able to begin what has become a major part of my work: the interpretation of spiritual or religiously creative personalities, in such a way that from the personality a light fell on their work and from their work a light fell on the former. For this I have received decisive help from phenomenological philosophy, especially its embodiment in Max Scheler."

The mention of Max Scheler at this point has its prehistory, namely Guardini's preoccupation with Simmel's, Wölfflin's, Dilthey's, Windelband's and Rickert's view of the world, literature and art. Their influence was so strong that Max Scheler, in his letter to Guardini from 1919, believed he recognised a strong influence from Rickert and Windelband after reading Guardini's first writings. Guardini himself often refers to the influence of Simmel, and in his third report on my life also to Dilthey.

Guardini's Rothenfels loan library

To answer the question of why so little of Guardini's "early" library still exists, you have to go back in time to 1927 to Rothenfels Castle, when Guardini became the castle's director. In the following years, he set up a castle library in the west wing. As Elisabeth Wilmes reports in her memoirs, Guardini "selected this literary collection ... and made it available on loan. In 1931, it comprised almost 2,000 volumes", including extensive collections of pictures and art-historical literature rather than entertainment literature. And "the German master storytellers were represented with representative complete editions, ... not only Gottfried

Keller's novels, but also all of Jeremias' writings, not only Eichendorff's works, but also a complete Brentano edition. The translations of Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky were available to the members of the Werkwochen. Leskov's narrative poems were also made available for recommendation. Before the philosophical conferences, the latest texts, for example by Newman or Kierkegaard, which hardly anyone knew, arrived for use. There was a preference for French literature, whether it was Francis Jammes' Idyll of the Hare novel, Bernanos' psychological novels or Claudel's translations." In a bay window in front of the library, there was a bench for nine readers and a bookshelf for which Guardini himself suggested Karl May.

On 16 March 1945, Guardini's Rothenfels library on loan was destroyed by an unfortunate circumstance in the publishing rooms of the Werkbund publishing house in Heinestraße, along with the entire old town and city centre of Würzburg. In 2005/06, Ingeborg Klimmer, then an employee of the Werkbund publishing house, reported in "Magnificat" on an expensive and ultimately futile repatriation: "In 1945, however, the Werkbund publishing house and the print shop were burnt during the attack on Würzburg, along with the library at Rothenfels Castle, which Guardini himself had built up. This had initially been confiscated by the Nazis, but was later bought back by Werkbundverlag." In fact, when the Gestapo confiscated the castle in 1939, they also confiscated the chapel with its sacred artefacts, vestments and liturgical books as well as the entire library. Guardini complained about this to the higher Gestapo authorities in Berlin, as these things did not belong to the Friends of Rothenfels Castle as the castle's owner, but to the independent "Rothenfels Foundation", and the library was even his personal loan. These items would therefore have to be returned. After some back and forth, this was done with regard to the chapel inventory. The library, on the other hand, was bought back by the publisher.

Only very few finds, a good 50 of the 2000 books with the old "loans" stamp have survived "somewhere" and "somehow", most of them are still in Rothenfels itself, others in Mooshausen probably borrowed there by Guardini himself. A few were probably taken home by Hans Waltmann from the publishing house and returned to the Catholic Academy's collection via his estate.

Childhood and school days in Mainz

For the early years in Mainz up to his school-leaving examination in 1903, we still only have the well-known memoirs of Adam Gottron and Philipp Harth, which Hanna-Barbara Gerl-Falkovitz had already cited in her Guardini biography in 1985. We know from Gottron that the Guardini brothers owned all the Karl May volumes. In Harth's "Mainzer Viertelbuben" it says: "Romano owned a bookcase with many books. [...] I listened with admiration when Romano described the contents of the books he had read. He was also very interested in poetry and he wrote poetry himself. [...] He translated Oliver Twist from English for school. I drew illustrations in his exercise book, which pleased the teacher and his classmates. I learnt about the book and other Dickens books that Romano lent me. The biggest and most beautiful book Romano had was Dante's "Divine Comedy" with illustrations by Doré. We often looked at these pictures and Romano knew how to explain them to me because he had read this book."

Finally, as far as Dante is concerned, reference should be made to Guardini's 1937 study "The Angel in Dante's Divine Comedy", which is preceded by the dedication in Italian "To the memory of my father, from whose lips the child plucked the first verses of Dante". This can be seen as an indication of a strong bibliophile upbringing by the father.

Studied chemistry in Tübingen 1903/04

There is also not much new information about his time as a chemistry student in Tübingen. His reading of Fritz Reuter has already been revealed in the previously published "Reports on my life". In the third report, Guardini merely confirms this: "I remember certain literary interests, but these were limited to authors such as Fritz Reuter."

It is now also known that he read Heinrich Hansjakob's "Stille Stunden" and was so taken with it that he summoned up all his courage to write a letter to the author on 15 January 1904. The letter was published in 1987 by Werner Scheurer in the "Heinrich Hansjakob (1837-1916). Festschrift on the occasion of his 150th birthday". It reads: "I have only read the `Stillen Stunden' from your works. Although I was unable to fully comprehend some of it, probably due to my lack of experience, I was so pleased with much of what you said that I really must thank you for all the marvellous views you expressed there. For example, your opinion of the soul of animals. God, how many times have I been laughed at because I didn't want to agree that such a poor animal should only have to work and be a nuisance and then nothing. Now I can at least refer to someone who thought and said all this much earlier and better than I did. And so I wish you, dear sir, that 'the old cart', as you call yourself, may continue to drive such delicious treasures as the 'Silent Hours' into the storehouses of Catholic literature for a long time to come."

Studied economics in the literary city of Munich 1904/05

Guardini then changed his place of study and his subject. He went to Munich and enrolled in economics. With regard to Munich as a city of art and literature, he noted in the already well-known "Reports on my life": "What was really significant for me at that time was the city and the artistic and literary air in it. I found inspiring friends, but, significantly enough, not among fellow specialists, but among art historians, literary historians and writers. At that time, I also became more involved in life. The peculiar mixture of big city and cosiness, interspersed with an artistic bohemianism that always grumbled about the stuffiness of the city and yet felt infinitely comfortable in it, had a liberating and stimulating effect on me. I went to the café and took part in the endless discussions about literature and the visual arts; I went to concerts, museums and exhibitions, looked around the beautiful neighbourhood - all still bound by the shyness I carried within me." It was here in Schwabing and the other neighbourhoods that he had the experiences that would leave a lasting impression on him. However, these experiences are also known to have led him to a deep religious crisis, triggered by a conversation with an art historian and Kantian at the fountain in front of the university.

For the thoroughly shy Guardini, these experiences were probably only possible thanks to his former classmates in Mainz, who were involved in the "Munich Free Student Association", the "Münchner Finken". He also found other friends there. Particularly noteworthy are the Silesian art historian Franz Landsberger (1883-1964); the later writer, actor and theatre director Rudolf Frank (1886-1979) from Mainz, who paid detailed tribute to Guardini in his autobiography "Spielzeit eines Lebens"; the Frankfurt native Recha Rothschild (1880-1966), who also created a memorial to the Munich "Romano" in her posthumously published autobiography; as well as: Ludwig Feuchtwanger (1885-1947) from Munich, brother of Lion and Martin Feuchtwanger, who later established himself as a publisher; and finally Ernst Lissauer (1882-1937) from Berlin, who a few years later became what we would today call a "shooting star" on the Berlin scene.

It is not only against this background that it becomes understandable what Guardini adds in his third biography for this period: "I also realised the importance of the literary work of art at that time, and both in Munich and in Berlin the circle of friends in which I socialised was important for this: some of them were productive people themselves. In conversation with them, I learnt to see poetry not only as a finished object of understanding endeavour, but I also came into contact with the process of creation itself."

Rudolf Frank confirmed in his memoirs, published as early as 1958 but not recognised by Guardini research until later, that the "cheerful scholar" Guardini was a "second Dante" who "much preferred ... to talk about the new Tristan novellas by Thomas Mann ..., about 'The Year of the Soul' by Stefan George and about Arthur Schnitzler's erotic 'round dance'" instead of studying economics. And on Guardini as a "reader", Frank noted: "I have never heard anyone recite Hofmannsthal's verses as quietly, unconsciously pure as his friend Guardini. Deep in the night in Michel Oppenheim's den, he read Andersen's whimsical allegory of the drop of water under the magnifying glass with a fine irony, read Wilhelm Busch long after midnight, and when morning dawned, Dante: "Nel mezzo di cammin di nostra vita"."

The Munich Finks also knew how to celebrate festivals. On 8 July 1905, the summer festival of this free association took place as Johannis-Walpurgis-Tag on Lake Starnberg, "the framework of which", as previously announced in the Allgemeine Zeitung, "is a secret medieval femgericht with witch burning and Walpurgisnacht, introduced by a pantomime ... [a] festival that will have a thoroughly artistic character, ...". In Frank's "Spielzeit meines Lebens" it says: And then "... they shouted Goethe's witches' howl, jumped through the fire in pairs and dragged the delinquent together with all the witch judges to the Blocksberg, the dance floor, which stud. ing. Ernst Weinschenk (whom the artisans called the Rococo Man) had effectively decorated as a witches' dance floor. Dreyfuß, the future public prosecutor, stood out among the witch judges and indeed looked devilishly like Fra Girolamo Savonarola. Romano Guardini, a second Dante, gazed into the turmoil with a superior smile." The Michel Oppenheim, Ernst Weinschenk and Max Dreyfus mentioned by Frank were also all fellow students of Guardini in Mainz.

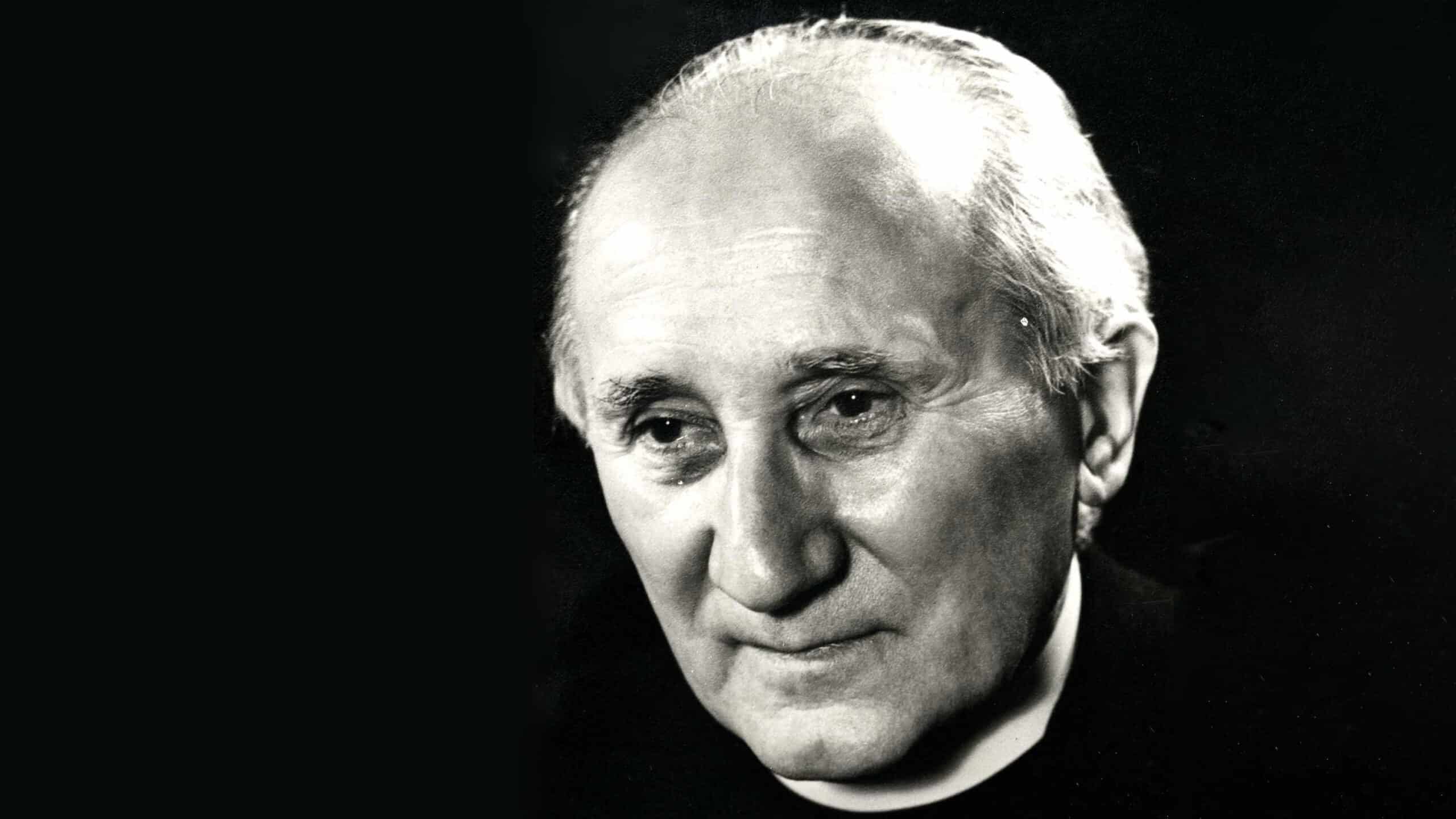

In his third biography (pictured left), Guardini then unexpectedly focuses on an already established figure in Munich literature at the time: Thomas Mann. "First of all, it was the literature of the time, that is, the authors around the Neue Rundschau. Thomas Mann made the strongest impression on me. The intensity of the creative process in his work made a strong impression on me. [...] And you can say what you like about authors like Thomas Mann; this much is certain, that there is a tremendous subtlety and precision of psychological analysis in them." Thomas Mann's "Fiorenza", for example, was featured in the "Neue Rundschau" in July/August 1905. Until then, it was only known from a hint in his posthumously published lectures on ethics that he had already read Thomas Mann during his student days. There it says: "Thomas Mann was a great artist. When I was a student, it was always an event for us when something new by him appeared."

But Romano Guardini's attention was also drawn to a literary epoch that had already passed, as can be read in his third biography: "In Munich, I also came into contact with Romanticism. The recently published works of Ricarda Huch and Marie Joachimi brought the romantic world closer; people from my circle of acquaintances were concerned with their philosophical and psychological theories. This brought me into contact with Novalis, Tieck, Brentano, Arnim, Wackenrode, and so on. I didn't lose this connection later on either."

It had been known since 1985 through Gerl-Falkovitz that Guardini had read Stendhal's "Aphorisms on Beauty, Art and Culture" on 12 June 1905, which was then on "loan" to the archives of Rothenfels Castle. In it, some passages on the subject of "style" had been specially marked by him.

The study semester in Berlin 1905/06

So far, only the almost exclusively negative memories of his semester in Berlin have been available from the first two "Reports on my life". There he speaks of the "austere working city of Berlin" and the "character of life there". Therefore, one could only feel comfortable in this city if one had a home-like flat, a fulfilling job or plenty of "surplus energy" to let off steam. His dark flat "near Bellevue railway station" was "anything but cosy", "but work was bad": "So I only had something on the side that winter. I had a lot of stimulating traffic, mostly from Munich. I also went to concerts and the theatre a lot - Ibsen in particular was performed wonderfully at the Lessingtheater, and I experienced the interesting experiments of the Reinhardtbühnen."

This stimulating dialogue "mostly still from Munich" refers to the fact that, according to the university's staff directory, at least four members of the "Munich Finches" moved to Berlin with Guardini: his friend Franz Landsberger, Heinrich Blase from Mainz, the son of the Mainz grammar school director, Max Dreyfuss and Ludwig Feuchtwanger. Interestingly, his brother Lion Feuchtwanger is also enrolled as a student at Berlin University for this winter semester. They will have met not least during and after the lectures by Simmel and Wölfflin. We also know from this list of people that Guardini lived at Calvinstr. 26 during this winter term.

This is significant because although the room may have been dreary, its neighbours, and very probably even its landlords, were none other than the musician-actor-literary couple Ettlinger and Moest: Josef Ettlinger was the director of the Neue Freie Volksbühne and editor of the magazine "Das literarische Echo". His wife Thea was a writer and Whitman translator. Friedrich Moest was an actor and senior director at the Thalia Theatre and artistic director of the Neue Freie Volksbühne. His wife Else was a former opera singer and now a singing teacher. Together, the Moest couple had been directors and owners of the Reichersche Hochschule für dramatische Kunst since 1901, which Moest had founded together with Emanuel Reicher in 1898.

It is very unlikely that Guardini, who was interested in literature and theatre, remained unaware of his neighbours' activities, even though the "Neue Freie Volksbühne" does not appear by name in his work, but only the Lessingtheater and the other Reinhardt theatres are mentioned. The Lessingtheater was under the direction of Otto Brahm at the time. On 8 November 1905, Ibsen's "The Wild Duck" premiered there with great success. In the third report, the previously known memory is made more precise by the statement: "The impression Ibsen made on me was also very strong, especially when I was able to see the brilliant performances of the Lessing Theatre in Berlin."

In his third report, Guardini mentions his Berlin readings: "I must also mention Jens Peter Jakobsen, especially his novellas. Of German literature, the great storytellers came close to me at that time, only to remain my friends forever, to whom I returned again and again: above all Gottlieb Keller, Eduard Mörike, Otto Ludwig, Storm (with strong reservations), etc."

Two further events belong to the context of the Berlin semester. In autumn 1906, Wilhelm Schleußner, professor at the Oberrealschule in Mainz, published a three-part article on Antonio Fogazzaro (photo 3) in the "Historisch-politische Blätter für das katholische Deutschland". In it, he characterises Antonio Fogazzaro (1842-1911), who is still alive, as the "most important personality in contemporary Italian literature". The previously unnoticed detail: the author explicitly names Romano Guardini as the translator for two translations in the footnotes. In an anonymous obituary for Wilhelm Schleußner in the "Mainzer Journal" in 1927, it says: "Two names characterise this round table and Schleußner's commitment to it quite well: Dr. K. Neundörfer and Dr. Guardini. Anyone who knows, for example, that Schleußner's articles in the Historisch-politische Blätter about or against Fogazzaro found their first seeds in these hours knows how fruitful this little "academy" was."

Guardini's co-authorship thus places this article at the top of his primary bibliography. The precarious thing about this contribution to Schleußner's article: a year earlier, in 1905, the Catholic Church had placed Fogazzaro's work "Il santo" on the "Index Librorum Prohibitorum".

In addition, Guardini's collection of poems and letters "Michaelangelo" was published in 1907 by the Jewish writer Hans Landsberg's Pan-Verlag in Berlin. He had probably already started translating the letters before the Berlin semester. For some of the sonnets, he was able to draw on as yet unpublished translations by the recognised translator of Dante, Petrarch, Carducci and Edgar Allen Poe, Bettina Jacobson (1841-1922). Hans Landsberg in turn had connections to Berlin literary circles, including the Ettlingers and the Moests, but also to the circles to which Simmel and Wölfflin belonged. In her latest publications, the art historian Yvonne Dohna-Schlobitten quite rightly emphasises that Guardini's selection, arrangement and commentary here provide a view of figures and works that already contains all the foundations of his later Weltanschauungslehre.

The theology student in Freiburg, Tübingen and Mainz 1906 -1910

New finds for the period of his theological studies in Freiburg, Tübingen and Mainz are becoming rarer again. There is still no "literary" hit for the Freiburg summer semester. The entry "Tüb. 10.3.07" in the private library in Suresnes Castle is W. v. Kügelgen's "Jugenderinnerungen eines alten Mannes". In a letter to Josef Weiger from November 1908, Guardini refers to John Ruskin's "Menschen Untereinander". It is relevant to his time at the Mainz seminary that he published a review anonymously in the Historisch-Politische Blätter in 1911 under the title: "Das Interesse der deutschen Bildung an der Kultur der Renaissance". This was a review of: Francesco Matarazzo's "Chronicle of Perugia" and Francesco Petrarch's "Letter to Posterity; Conversations on Contempt for the World; On His and Other People's Ignorance". The latter volume was translated and introduced by his fellow student and friend Hermann Hefele from Tübingen. Both volumes were richly illustrated and published by Diederichs Verlag in 1910.

The doctoral student in Freiburg from 1912 to 1915

During his doctoral studies in Freiburg, Guardini read more general literature at the Collegium Sapientiae at Karthäuserstr. 41, probably as a balance to his studies on Bonaventura. Most of the references come from the letters to Josef Weiger published by Gerl-Falkovitz in 2008. In February 1913, Guardini gave him the recommendation: "But you should also read Reuter and Raabe. [...] Raabe's Eulenpfingsten comes later, must be bound." A letter in December 1913 reports on his own reading of Raabe. There is now a revealing reference to Raabe in the third biography: "In my second period in Freiburg, at the suggestion of E.M. Roloff, I came across Wilhelm Raabe, who was very important to me for a long time. I loved the intensity of the imagination, the clarity of form and the richness of the language, as well as the certain seclusion and tranquillity of the mood." This inspirer, Ernst Max Roloff, was Guardini's "bodyguard" in the Freiburg Catholic student fraternity Unitas during his doctoral studies. He was the editor of the "Lexikon der Pädagogik". Guardini co-wrote several of Roloff's articles as an unnamed "ghostwriter".

For the period between June 1913 and July 1914, the following references to Brentano can be found: the collection of poems "Der geistliche Mai. Marienlieder aus der deutschen Vergangenheit", the selected poems by Detlev von Liliencron, the volume selected by Hermann Hesse "Der Zauberbrunnen. The Songs of German Romanticism", Richard Wagner's "Jesus of Nazareth" and "Goethe's Letters to Mrs von Stein".

Guardini's two recommendations on how best to engage with legends and fairy tales, which are unfortunately not yet available again in the edition of his works, show that he spent a great deal of time with old and collected legends and fairy tales during these years, but also with the legendary and fairy tale-like narrative art of the Romantic period and the present, somewhat similar to his essay on engaging with art from 1912. These recommendations can be found in 1918 under the pseudonym "Dr Anton Wächter" in the monthly magazine "Heliand". Also under the name "Anton Wächter", a review essay entitled "Thule oder Hellas? Classical or German education?" The volumes of the Thule series discussed therein, published by Diederichs-Verlag since 1911, are in Guardini's private library and have been worked through with entries. Based on the ex libris stamp "R. A. Guardini Sac." contained in several volumes, which he only used between 1913 and 1915, it can be concluded that the volumes mainly belong to his Freiburg reading programme.

Conclusio

In his early years, Guardini was therefore particularly preoccupied with "controversial" contemporary literature. He explicitly emphasised the importance of Thomas Mann. Guardini also dealt extensively with the literature of antiquity, the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, particularly in the corresponding editions published by Eugen Diederichs-Verlag. From the very beginning, he also paid particular attention to fairy tales and legends or fairy-tale and legendary literature. He also read a lot of books by "reform Catholic" authors. He also read the magazines "Neue Rundschau" and "Hochland". In view of his seminary experiences in Mainz and the anti-modernist attitudes in the Roman Catholic Church, he remains cautious with his own statements on the fruits of his reading and publishes his first texts anonymously or under a pseudonym. Overall, his own expressionist and phenomenological attitude to questions of character and style becomes clear. He ultimately experienced all these "literary works of art" as "the bridge to the world that SHOULD one day come". For Guardini, the eschatological "promise" inherent in the work of art is part of the "essence of the work of art".