Strangely enough, in many areas of historiography, the military of the "belligerent states" only plays a minor role when it comes to wars. As essential as it is for historical analyses to explore the political actions, plans and motives of those in power, or to examine the effects of the war on the civilian population, which was more or less passively affected: The course of events ultimately depended on the functioning or non-functioning of the "military machine", and that ultimately means the collective and individual behaviour of the people who made up the warring armies.

The members of the military thus appear to a certain extent as extras on the Theatrum Belli - obviously present and available to the directors of the cabinet war. In the historical narrative, they mainly appear in the form of numbers: These quantify the size of the armies deployed, enumerate the units thrown into battle in battles and skirmishes, also quantify the "losses", today of course rarely without formulas of moral shock about that "bloody" age.

Nevertheless, it usually remains with statements such as that Frederick II with 40,000 Prussians defeated Field Marshal Daun with his 70,000 Austrians, or that "the Prussians" defeated "the Austrians" and vice versa. The results lead to the realisation of which army was probably the "more modern" and better and which commander was the wiser.

In recent decades, the focus of historiography has shifted away from the plans and objectives, successes and failures of leading rulers, politicians and commanders, and also from those of states as supra-personal actors - and the "raison d'état" that supposedly determined their actions. At the same time, however, research today has also largely moved away from classical war and military history and with it from the question of the course of campaigns and hostilities. As a result, the investigation of individual events has also receded, additionally justified by the justified methodological doubts as to whether a battle, for example, as an event that is ultimately "unobservable" in its contingency, can somehow be depicted or even reconstructed.

On the one hand, today we tend to enquire into the structures and mentalities that guided and limited the actions of all actors in the respective era. On the other hand, we also ask more about the perceptions and interpretations of contemporaries, both those of professional observers and opinion-makers, as well as those of the people who experienced the war at the micro level, both the "civilians" and the soldiers.

In this way, microhistory can distil extremely exciting and illuminating highlights "up close" from the now familiar first-person documents of ordinary soldiers and subaltern officers from all over Europe and from a period of decades. This is an extremely productive approach which, paradoxically, also puts the individual event (and thus to some extent the classic treatments of campaigns, battles and sieges) back into perspective, because this forms the framework of personal experience and memory.

However, it cannot avoid the problem that the source material is rather limited, despite significant new discoveries and highly commendable editions. The objection that it is possible to distil plausible impressions from such individual voices, but not a representative picture of the experience of the vast majority of "silent" contemporaries, is ultimately difficult to refute.

Perhaps it makes sense to take another small step back and take a closer look at the "midi level". The regiments and armies, i.e. the differentiated and complex organisations of thousands to hundreds of thousands of people, not just soldiers and officers, not just men in uniform, with or by whom the Seven Years' War was fought, could be described as such. Only a few aspects and questions will be addressed below.

If we speak only of the war in Central Europe, we must assume that at least well over half a million soldiers were directly involved in the theatre of war at the same time. The armies of Prussia and various small German states can be counted as fully mobilised, while the other major powers left parts of their military potential in remote territories or, as in the case of Great Britain and France in particular, deployed them in the other theatres of this "world war" - albeit with comparatively much smaller numbers of troops than on the European mainland.

This figure is probably far too low, especially as it only takes into account the actual soldiers who were counted too accurately in the lists. As a rule, their wives and children, some of whom were travelling with them, were not counted, nor were the carters, farmhands and other camp followers of both sexes, who were still quite numerous in the 18th century.

The Prussian army as a pattern and model?

In some respects, it is obvious to regard the Prussian army as a model for the military of the 18th century. No other Central European army of this era has been the subject of so much research and literature. Frederick the Great's army - like the king himself - is one of the "stars" of history. And it was - at the latest with and since the Seven Years' War - already in the 18th century. Even for contemporaries, Frederick the Great, the Prussian military state and the appearance of his troops were a source of fascination that was not only practically imitated by other armies, but was also the subject of a wealth of publications.

In the "long 19th century" up to 1914 (or 1918), the flourishing of historical scholarship and the desire for tradition within the Prussian army led to countless publications dealing with the politics and warfare of the "Great King", but also with the details of individual troop histories, biographies of officers and not least the uniforms, equipment and armament of the Frederician army.

Although crises such as the Prussian collapse of 1806, periods of disinterest and, most recently, the devastating effects of the Second World War have resulted in enormous losses of source material, we know far more details about the Prussian army than about the Austrian military forces of the time. However, the focus here is less on what was special about the Prussian military and more on what was typical of the period, as the European armies of the 18th century were fundamentally very similar, both externally in terms of clothing and armament, as well as in their hierarchies and organisational structures.

"Standing armies of mercenaries"?

When we talk about the armies of the belligerent states of the Seven Years' War, we usually refer to them as "standing mercenary armies". What does that mean? Who stood when and what does mercenary mean? Ultimately, this term serves more to differentiate from the previous and subsequent army constitutions than to provide a clear picture. In fact, many of the basic structures of the Prussian army, as well as those of other European armies in the mid-18th century, still corresponded to those of the early modern mercenary armies. In other words, they were composed of individual regiments, each of which represented economic, legal and social units in their own right. The idea of the army as a top-down, hierarchically organised and centrally administered state institution only dates back to the second half of the 19th century.

The basic elements of army structures originated in the 17th century. The regiment was the unit that was independently raised, formed and equipped at its own expense by a military contractor, usually known as a "colonel", to be deployed on behalf of a mostly princely warlord for a limited period of time, usually for individual campaigns.

After the Thirty Years' War, in which the armies had ultimately proved to be almost unmanageable, the need of the potentates to have permanent military power at their disposal at all times to secure their own rule internally and as a political instrument externally called for "standing troops". The regiments were no longer to be disbanded after the war, but were to "remain standing". Initially, this only meant that the warlord concluded long-term contracts with the mercenary contractors and at the same time had to secure their long-term financing.

Nevertheless, one must be careful with the term "standing army". Traditionally, the standing army is counted among the basic elements of princely "absolutism" in the "Baroque era" (to mention two highly problematic terms). Traditionally, a clear starting date is given for each army - usually deep in the 17th century - which refers to the establishment of the first force that was not disbanded.

Sometimes this led to quite daring constructions of a regimental genealogy, which flourished especially in the historicist 19th century. The age of a regiment was considered decisive for its reputation and determined its place in the "master lists". The fact is that even well into the 18th century, many regiments were disbanded almost regularly at the end of wars, but also repeatedly due to a lack of funds. Even where the units still appear complete on the patient paper, a closer look at the lists shows that often so many soldiers were dismissed and horses sold that it is not even possible to speak of cadre structures for future rearmament. When needs and opportunities changed, new units were formed.

Even in Brandenburg-Prussia, which was always regarded as an example of a continuously growing army, over a hundred independent units were established and disbanded between 1655 and 1713; far fewer remained in existence permanently. It was only with King Frederick William I (reigned 1713-1740) that a continuous increase in the size of the army was actually observed from 1717 onwards, but this remained a special case in Europe for a long time to come.

The longer and the more officers and soldiers could be permanently paid and kept in service, the more the warlords' powers of control were extended and gradually enforced. In this way, the originally private-sector system changed steadily without being fundamentally abolished. In the middle of the 18th century, rulers almost everywhere had the final decision on the appointment of officers, determined the type of armament and equipment and regulated training. The Prussian army was quite advanced in this respect, especially as the relationship between centralised regulation and decentralised practice proved to be exceptionally effective compared to other states and their armies.

From today's perspective, it is not so much the remnants of private enterprise and autonomy within the army, which can also be found in all other areas of state and society in pre-modern times, that are astonishing, but rather the fact that the responsible observance of the rules and regulations by the officers of the Prussian army apparently functioned better than elsewhere, despite the lack of a developed control bureaucracy.

In the middle of the 18th century, many things were still regulated on a decentralised basis at regimental level - as the basic military unit of around 1500 soldiers (in the Prussian infantry) under 50 officers. The regimental commander received a lump sum with which he had to run his regiment like a company according to economic principles within the framework of the rules and regulations. At the level below this was the company economy, in which the captains (Hauptleute) were in turn responsible as a kind of dependent sub-contractor for the companies under their command (in Prussia 12 per regiment).

Although more and more was prescribed and specified centrally, implementation remained with the individual regiments and companies. Due to the long distances and difficult communication channels alone, this was more efficient than a non-functioning centralised management and control system. The personal profit motive of the regiment and company commanders was certainly factored into this system.

Officers

If we focus on the structure and practice of the armies in the era of the Seven Years' War, it makes perfect sense to start with the officers, even if this runs counter to our social-historical conscience. Officers were clearly separated from ordinary soldiers in the early modern period - in some respects they remain so to this day through their training and careers, even though the barriers of old-style society no longer exist. Even if there were stories of advancement from the very bottom through good fortune and probation, officers, with few exceptions, came from the higher strata of estates society, the nobility and the urban or landowning bourgeoisie.

It was not only the social background and codes of behaviour that contributed to a common sense of status, but also the career paths, which for some officers involved one or more changes of employer, which was not a moral or political problem in the states of the Ancien Régime. This established horizontal mobility of officers and the associated transfer of knowledge naturally contributed significantly to the fact that armies resembled each other more than other areas of regionally characterised societies. Moreover, an international adaptation of ranks had been established since the late 17th century, not least through the practice of exchanging prisoners of war.

Even in the 18th century, the officers of the Prussian army were regarded as an unusually homogeneous group compared to other European armies, as their proportion of nobility was particularly high and the majority (around 70 %) were recruited from the native nobility of the Brandenburg-Prussian dominion. The rest were nobles from abroad and a small proportion of commoners, of whom there were significantly more in other armies.

Several factors worked together here: One prerequisite was that the territories of the Kingdom of Prussia had a very numerous, but on average not very wealthy nobility, for whom a military career offered one of the few employment opportunities befitting their status. The regional differences were nevertheless clear. Wherever noble families were strongly networked across the borders of the Old Empire's fragmented dominions, they had several options and various loyalties to consider. Members of the particularly influential and wealthy aristocratic families were much more reluctant to join the army, as the close personal ties to the king that this entailed limited their position as the estates' counter-power to the ruler.

An important factor for the unity of the regimental officer corps was that the regimental commander (and with him, unofficially, usually the community of officers of a regiment) decided who was proposed to the ruler as an officer. This is where family and neighbourhood networks came into play. This ensured that often close and distant relatives and generally many noblemen from a region served as fellow officers in a regiment.

It is true that the close royal control and the requirement, tightened by Frederick the Great in particular, that only nobles should be made officers if possible, prevented regimental chiefs from being able to pursue their own personnel policy too independently. However, it was of course also welcomed when regimental chiefs who came from foreign services or belonged to the non-Prussian aristocracy used their connections to bring foreign nobles into the Prussian service as officers.

The usual course of an officer's career took place over decades in the regiment in which a young nobleman joined - usually as a Frey corporal with the rank of non-commissioned officer - and in which he could be accepted as an ensign after a few years as soon as a position became available. Commoners could also become officers in the Prussian army, and their numbers grew slowly but steadily. Even if young aristocrats or sons of the upper middle classes formally served in the ranks "from the bottom up", their path to becoming an officer was mapped out from the outset. For "real" up-and-comers, many years of service or special knowledge and skills (such as in artillery) were a prerequisite for being accepted.

Officers who remained in service and did not leave "their" regiment after a few years (which was quite common, however, especially as service was a financially subsidised business for subaltern officers) usually only left it at an advanced age and after successful promotion: officers were only transferred to other units relatively regularly when they reached the rank of staff officer, from major upwards, but there were also careers from ensign to colonel within a regiment.

As a result, the officer corps of the regiments were highly homogeneous and cohesive, which characterised a specific "regimental culture". It is therefore more correct to speak of "the" officer corps in the plural than of "the" Prussian officer corps, which did not yet exist in the 18th century. The officers' self-image as a community was also expressed in particular in the uniform, which was exactly the same for all officers within a regiment - from ensign to colonel - and showed no insignia of rank. In the small world of the regiment, people knew each other well and beyond that, the rank of an officer could at least be roughly estimated by his age.

In addition to this protracted career, which was accelerated by the high bloody losses in the war, the armies of the era also continued to include the aforementioned international mercenary armies.

careers of officers who changed employer. These were always officers from less permanently "standing" armies who became unemployed during reductions, but also professionals with diverse service and war experience who were in demand for the transfer of knowledge and practical skills and could rise to high ranks far more quickly. There they encountered another group of younger gentlemen who, thanks to their aristocratic origins, played a leading role that was a matter of course in the society of the estates.

Of course, we are only talking about around three per cent of the army in terms of officers; for every Prussian officer there were around 30 "enlisted men", i.e. non-commissioned officers and soldiers, although in some other armies there were proportionally a few more officers.

Soldiers

For the majority of soldiers in the "standing mercenary armies", there was no prospect of a career or the aristocratic idea of individual fame and honour, but only a more or less long period of life in uniform, which, although not very attractive from today's perspective, was still a good alternative depending on their life situation. In any case, a look at the surviving lists shows that the prejudice long held by historians that the armies of the 18th century were recruited almost exclusively from the "yeast of the people", from the lowest classes, from day labourers, beggars

and strays, is by no means true.

Even if 18th-century armies were able to draw on conscripted subjects, as in Prussia through the cantonment system, which assigned each regiment a specific recruiting district, the basic structures of the mercenary system remained influential. Whether it was in fact primarily the conscript cantonists who formed the stable core of the Prussian army, or whether the long-serving professional soldiers were the formative element, cannot be conclusively decided.

Although the Prussian canton system was indeed a particularly effective model, its special status is perhaps overestimated. In fact, most sovereigns - including the Prussian kings - were keen to ensure that their own population could pursue productive activities in agriculture and crafts in their sparsely populated territories. Economically valuable groups were usually exempt from military service altogether.

It was therefore considered desirable to fill the armies with as many "foreigners" as possible. However, this term is misleading: only very few soldiers came from far away, but by far the most numerous came from closely neighbouring regions, especially in the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, which consisted of around 300 different independent dominions, most of which were still made up of many scattered territories.

You were often a "foreigner" even before the gates of your home town or in a neighbouring village if it belonged to another lord. In addition, a significant proportion of the soldiers in the Prussian army listed as "foreigners" came from the various population groups in their own country who were not covered by compulsory service in the cantonments; they were therefore often children of the country who were not called up as cantonment soldiers, but were recruited as capitulants with temporary contracts. They were thus recruited as "mercenaries", as were those who came from outside Prussian territory - in principle voluntarily and then for a contractually agreed period.

Men enlisted in the army for a variety of reasons: one important reason for becoming a soldier was certainly material hardship. People's lives in the early modern period were characterised by scarcity. It was not only the lowest classes whose existence was directly threatened by crop failures and other economic crises. The military profession offered many people a modest but secure livelihood, clothing, food and shelter.

However, other positive incentives also played a role, which have often been ignored by the bourgeois criticism of the military that is still popular today: The uniform certainly conferred a certain social prestige as the king's armour-bearer, and it indicated that its wearers were no longer subject to the jurisdiction of their lords of the manor as hereditary peasants, for example.

Given the uncertainties of life in general, the difference between war and peace does not seem to have played the role we ascribe to it today. For conscripts and "mercenaries" alike, it was true that they knew they were at the mercy of fate, which God alone would determine. Doing one's duty as a good subject was pleasing to God and therefore important for eternal life. Of course, war in particular also offered small opportunities, at least in the imagination of those who allowed themselves to be recruited: an escape from restrictive personal circumstances had always been a motive, a thirst for adventure, perhaps even booty. The latter motives applied especially when there was the prospect of going to war.

However, the demand for soldiers exceeded the pool of volunteers at almost all times. This is why the compulsory service of the state's children proved to be the mainstay: in times of peace, it was sufficient if only relatively few men were drafted each year, in Prussia only those who were at least 1.72 metres tall, but preferably 1.80 metres or taller, which was far above the average of the male population at the time. This reduced the pressure on the population, as only tall men were at risk of having to become soldiers.

During peacetime, the trained cantonists only had to come to the garrison once a year for a drill lasting several weeks; otherwise they remained in their home environment as farmers or craftsmen. The daily service in the garrison towns was mainly carried out by the "foreigners" throughout the year. In peacetime, they also worked in the garrison town as day labourers or craftsmen in a civilian occupation, as drill and guard duty only took up part of their time, and the pay alone was barely enough to live on.

The forces of solidarity within the regiments and companies proved to be essential for the stability and resilience of the army: the common origin of the soldiers from the same region, often from the same village, and even family ties played a major role here, especially among the Prussian cantonists. During the war, there was also the vital co-operation of comrades, from the daily preparation of food in the tent community to the necessary cooperation in battle. Finally, the role model function of the officers and not least the pride in the honour of one's own troop unit also played an important role, especially among the "foreigners" for whom the regiment and the army had become home.

For most of them, the transition to military service meant that they had to cope with the cultural shock that was expected of them. "Dressing a fellow and giving him the air of a soldier so that the farmer comes out" - in other words, comprehensive socialisation in a foreign environment was the first task of the instructors in the Prussian regulations. Young men, who had received their entire education in the simplest agrarian living conditions, had to get used to an upright posture and keep themselves and their elaborately designed colourful uniform - for some probably the first complete clothing of their lives - meticulously clean.

The training of soldiers was very demanding. The infantry, in particular, focussed on drill with the firearm. Operating the muzzle-loading rifle required a complicated sequence of movements that demanded constant practice. In order to be able to fire the smoothbore shotgun at the greatest possible distance, the barrel had to be long, and in order to be able to fire such a long and heavy weapon in rapid succession, soldiers had to be as tall as possible. If the Prussian infantry could operate in 200 metre long lines on the battlefield, only three men deep, they were considered almost invincible thanks to their discipline and rate of fire of more than three shots per minute. The cavalry required extremely thorough riding training, which required them to act in closed formations.

The army at war

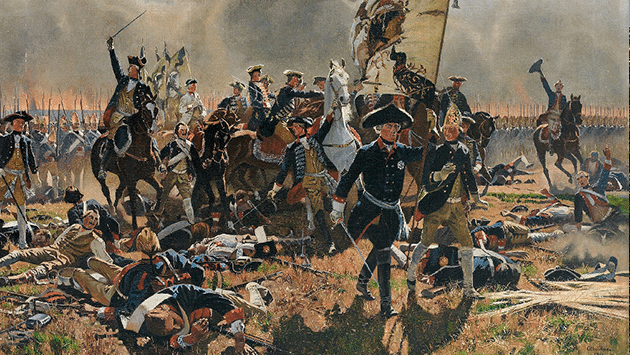

As a choreographed catastrophe, the battle was certainly the most dramatic test for the cohesion of the military units: If the soldiers kept their nerve in the apocalyptic hell of the battlefield, surrounded by the deafening thunder of rifle volleys and gunfire, in the face of masses of killed and wounded comrades, continued to respond to their officers' orders and remained in their formation, this showed the success of military socialisation. There is evidence of the collective pride of military units, which spurred them on to special achievements, especially in crisis situations.

However, the self-confidence of the experienced professional soldiers also set limits to some of the impositions made by the leaders: The well-known anecdote in which soldiers reply to the Prussian king, who asks them to attack again with the words "Dogs, do you want to live forever?", that enough has been done for the day's pay, is certainly true to reality. However, battles were rare in the wars of the 18th century; their strategic importance was often low enough in relation to the bloody losses that threatened the armies involved.

The everyday life of soldiers in the Frederician Wars was determined by the daily pressure to survive. They marched and camped day in, day out. Small battles alternated with phases of idleness in camps and shelters, but also with hard labour and constant danger during weeks-long fortress sieges. Infectious diseases in the quarters, poor medical care and malnutrition cost the lives of far more Prussian soldiers than the fighting itself.

The daily supply of food for men and horses was a key problem for the army commanders of the 18th century, but also for each individual soldier. For all their ability to suffer and their resignation to fate, which impresses and irritates the modern observer, this was also where the limits of obedience lay. If the soldiers had the impression that their contractual relationship was being cancelled from above - due to a lack of supplies, missing pay or unjustified demands - units collapsed in passive refusal or mass desertion. Here, perhaps even more clearly than in the exceptional physical and psychological situation of battle, it became clear what held the "standing mercenary armies" together, or not.

All of this, which we can prove from the Prussian example thanks to previous research, probably also applies to other armies of the era, with one or two specific deviations.

One important question has not yet been analysed in detail, namely how the armies changed over the course of the Seven Years' War. The need for soldiers increased exponentially in times of war, when armies were enormously enlarged and also had to make up for losses. When the big men ran out, the smaller ones were also drafted; the smallest and weakest were sent to garrison regiments as fortress garrisons and those who were not fit to be soldiers but were reasonably healthy were drafted as waggoners.

During the Seven Years' War, the Prussian cantons, whose reserves were now ruthlessly exhausted, also reached their limits, especially as a considerable part of the country was occupied by the enemy, such as East Prussia and some of the western provinces. As a result, the regiments lost their regional unity, which was considered one of the foundations of their fighting strength. There can be no doubt that the horrendous losses meant that even in the middle years of the war not too many of the thoroughly trained, long-serving professional soldiers of the peacetime army were still alive - a comparison with the First World War 1914-1918 is entirely appropriate here. The percentage mobilisation rate of the male population was not reached again until the 20th century.

It can be assumed that not only the Prussian, but also the other "German" and European armies had little resemblance to those that had gone to war in 1756 by 1759 at the latest, but were increasingly composed of a conglomerate of forcibly conscripted subjects, forcibly recruited inhabitants of the newly occupied territories as well as enlisted prisoners of war and more or less "voluntary" mercenaries of various origins and motivations.

Nevertheless, these armies continued to fight and march into their seventh year, and the history of war provides evidence that they were no less effective and flexible than at the beginning of the war. The idea that the armies of the Ancien Régime were made up of "slaves" driven into battle by force and without will is, on critical examination, unrealistic: it stems from the polemically exaggerated pamphlets of the enlightened military reformers of the late 18th century and the protagonists of universal conscription in the 19th century, who portrayed the old system as a gloomy antithesis.

No army could function on the basis of mere coercion, nor would it have been enforceable; an elaborate terror system with armed security forces behind the front, as used by the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century, was still unimaginable in the 18th century anyway.

Although the majority of soldiers obviously served willingly, desertion was a major problem for the armies. This was not necessarily because, apart from certain situations in war, there were so many more deserters than at other times. The problem was that soldiers in the 18th century were expensive and difficult to replace. In the old, organised society, state access to many population groups remained very limited; the "universal conscription" of nation states was still a long way off.

Recruitment involved considerable costs, as did the uniform and equipment as well as the long training period that a good soldier needed. For this reason, the draconian punishments threatened to deserters only ever affected a few unlucky individuals as a deterrent. As soon as there were too many, especially during the war, general pardons were issued, and some who had 'lost their way' were quietly reinstated. Even defectors who were taken prisoner of war by their former employer were often pardoned if they were big, strong and healthy.

Armies as social entities

Let's take another look at the internal structure of the European armies of the 18th century. They were already made up of different types of troops, which not only had different tasks to fulfil, but also had different social statuses. Analogous to civil society, class boundaries and hierarchies can be observed within the army, although these have not yet been systematically researched.

It is true that the infantry formed the majority of armies and always formed the centre of the order of battle. But it is easy to get a skewed picture if we think of the typical soldier of the era only as an infantryman: Around a third of armies were cavalry units. They had many more volunteers; horsemen were better paid, did not have to march much and were better able to provide for themselves during the war thanks to their deployments and mobility. On the other hand, their training, especially in riding in formation and fighting with bare arms, required different qualities than the drill of the infantry, who had to fight in closed units in linear tactics and, above all, had to be trained to function as part of the 'shooting machine' and stay in line even in extreme situations.

The artillery was hardly significant in terms of manpower, but of increasing importance in the war; it made demands other than just physical ones. Traditionally, it still had a special social position within the army in the 18th century and for a long time retained a manual, guild-like character. Even for the ordinary gunners who operated the guns, technical knowledge was required; even more so for artillery officers, the social capital of aristocratic origin and a long period of service were not sufficient, and accordingly there were relatively many commoners with a higher education.

In peacetime, the Prussian army, like most other armies, consisted only of the regular regiments of infantry, cavalry and artillery. During the war, it quickly became apparent that this was not enough, as Austria and Russia had a considerable advantage in the day-to-day small-scale war for supplies and supply routes. The mobile and independent fighters that the House of Habsburg brought from Hungary and the Balkans and the Russian Empire from its steppes posed a constant problem with their raids and forays beyond the major battles and sieges. Although Maria Theresa's Hussars, Pandurs and Croats from the military frontier against the Ottomans had already been encountered in the wars of the 1740s and their effectiveness had been painfully experienced, only inadequate consequences had been drawn from this until 1756.

It is true that regiments of light horsemen - modelled on the Hungarian hussars and clothed accordingly - were raised as a type of troop within the standing armies in the Prussian as well as in most other "western" armies. Light infantry, however, was completely absent in Prussia; it was only raised during the war in the form of free battalions. There was no provision for conscripted cantonment soldiers; volunteers had to be recruited at short notice, often adventurers and deserters from other armies. As a result, such troops were considered unreliable, which was confirmed in many cases.

For officers, too, joining such units with low social prestige and the prospect of being discharged at the end of the war was rather unattractive. Up-and-comers who were able to distinguish themselves in the Small War and later joined the regular army

career tended to be the exception.

A fundamental problem of warfare in the 18th century was common to all armies: what the armies did not have at all in peacetime was militarily organised personnel for logistics, supplies and transport. In the Seven Years' War, only a few officers and a few civil servants were responsible for supplying the armies, and for everything from buying food to engaging the local population with their wagons and draught cattle for transport. There is no need to explain how much this limited the mobility of larger numbers of troops, and it also becomes clear why warfare in areas with low population density and therefore few resources immediately led to

biggest problems.

At the lower level of the regiments and battalions, it was on the one hand the men conscripted in the cantons and on the other hand the waggoners and officers' servants enlisted from the country as required, as well as the tolerated camp-followers of both sexes, craftsmen and sutlers, and the soldiers' wives and families travelling with them, who had to ensure the day-to-day survival of the troops if the regular supplies from prepared magazines and the markets of the regions they passed through did not work, which was often enough the case.

Although the army commanders took great pains not to allow the huge, cumbersome troops that had characterised the Thirty Years' War, these uncounted soldiers were perhaps no longer as numerous in the Seven Years' War, but were still as indispensable to the functioning and survival of the armies as they were to them.

The regular efforts to limit and reduce the number of non-combatants were tactical and economic. They were hardly orientated towards socially defined gender roles.

The military of the 18th century was not yet the all-male society that it has long appeared to be in modern times. The proportion of women in the armies of the pre-modern era has so far been insufficiently recognised and practically ignored by the historiography of the 19th and 20th centuries. Even cross-dressers, i.e. women who served as soldiers - officially unrecognised - do not seem to have been so rare in the armies, despite strict prohibitions. In any case, it can be assumed that there were many more than the six women soldiers per company that were officially allowed to go to war.

We hardly ever know even approximate numbers of the men and women of those sub-military classes within and around the armies, nor do we have any first-person documents of such individuals. Even a "military history from below" cannot reach such "basement floors" due to a lack of sources, but a historiography of the armies and war in the old society will have to research the diverse aspects of early modern military societies even more specifically in the future.