Bach is often regarded as a genius, but - in contrast to Handel or Telemann, for example - not an urbane church musician. This judgement is based on ignorance.

Hermeneutic horizon

Bach - an intellectual of the 18th century

Although Bach was not an academic, his (grammar school) teachers in Eisenach, Ohrdruf and Lüneburg introduced him to contemporary philosophical and theological thought. In Eisenach and Ohrdruf, influences from the theological faculties of Jena and Leipzig dominated, while the Lüneburg teachers had almost all acquired their academic degrees in Wittenberg.

Last but not least, Bach endeavoured to acquire and purchase appropriate literature in his mature years, which meant an enormous financial outlay and was not at all typical for a church musician. Which is why Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, for example, listed every single book from his father's library in his necrology - 52 volumes, some of which were bound together with several writings in one volume. In addition to pietistic edification literature, there are, for example, collections of sermons (postillas) on the church year. In 1742, Bach acquired the Altenburg edition of Luther and other orthodox-dogmatic textbooks in an antiquarian bookshop. "These books and writings undoubtedly served as a theological working tool for the textual exegesis required by Bach as a church composer within the framework and in continuation of the preaching function of the poems intended for church music", as Hans Heinrich Eggebrecht writes.

However, the so-called Calov Bible, which contains a number of marginal notes from Bach's pen, is of central importance. His annotations date from the last two decades of his life; they revolve around questions of worship and the role of music in it. The entry on 2 Chronicles 5:3 is significant for our context: the chronicle describes the dedication of the temple by King Solomon, which is accompanied by the Levites playing timpani and strings. This scene was also depicted as a decorative title page on the Eisenach hymnal of 1673, which Bach must have been familiar with since his childhood. Bach's astonishing commentary on this temple scene reads: "NB. With devout music, God is always present with his grace."

This close reference to God in Johann Sebastian Bach's music can also be clearly seen in various prefaces and comments on his compositions. He prefaces his little organ book (BWV 599-644), written between 1708 and 1717, with the following:

"Organ booklet. In which a beginning organist is given instructions on how to perform a chorale in all kinds of ways, and also how to become proficient in the pedal studio by playing the pedal completely obbligato in such chorales. In honour of the highest God alone, to teach oneself from it."

This early masterpiece of chorale-related organ music already shows the unity of secular and sacred music, here in the form of the influence of Italian-influenced concertante writing, which stems from operatic and instrumental music. The combination of cantus firmus arrangements of the North German Protestant type with "modern" Italian concerto writing in an instrumental or arioso idiom, including the trio

principle goes far beyond contemporary works. This applies not only to the formal quality, but also to the affective richness of the tonal language and the close connection between word and tone in terms of compositional technique, figuration and movement; in short, the eloquent character of the organ works is obvious to the senses. These details "characterise the image of the Orgelbüchlein as a 'dictionary of Bach's musical language', in which there is diversity in the unity and unity in the diversity of musical ideas", as Michael Kube says.

The connection between music or music lessons and praise of God, which is evident in the preface to the Orgelbüchlein, is induced by the subject matter of music itself, i.e. it is to be understood as an essential element of music, as Bach impresses upon his pupils in his instructions on the continuo:

"The basso continuo is the most perfect foundation of music, which is played with both hands, in such a way that the left hand plays the prescribed notes, while the right hand adds consonances and dissonances, so that this gives a melodious harmony for the glory of God and the permissible pleasure of the mind and, like all music, the basso continuo should not have a finis and final cause other than the honour of God and the recreation of the mind. Where this is not taken into account, it is not real music but a diabolical plagiarism and a gimmick."

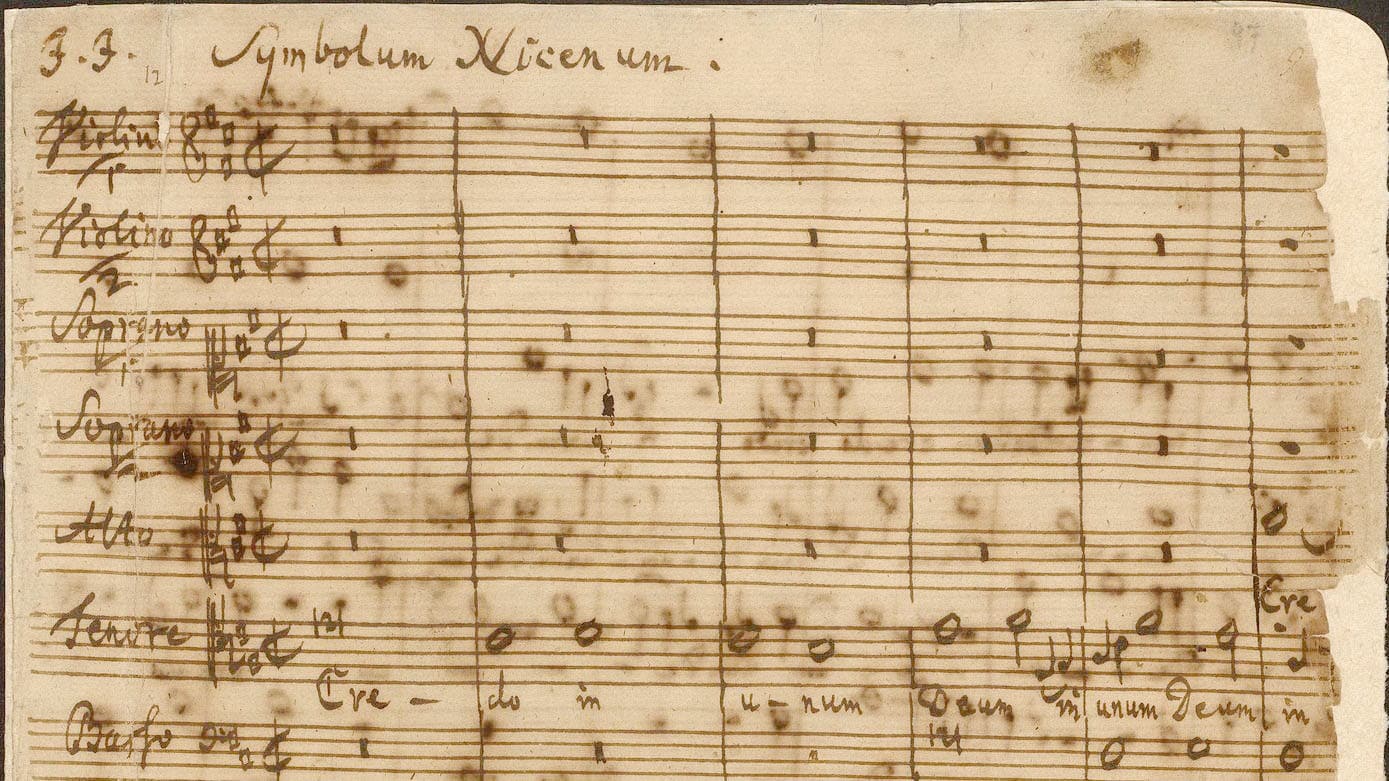

A further indication of the religious background to his teaching and composing is provided by various comments added to the compositions. Above the first attempts at composition by his son Wilhelm Friedemann (1710-1784) from 1720 (written under his father's guidance), his father wrote: "In Nomine Jesu". Bach often prefixed his own scores with a J.J. (Jesu juva). Or he placed an S.D.G. (Soli Deo Gloria) at the end of a score. This practice even serves as a dating criterion in the case of the Mass in B minor (BWV 232) with regard to the date of composition of the individual parts of the Mass.

The philosophical and theological implications of many of the technical and compositional peculiarities of the personal style emerge in the context of his entry in 1747 into the Corres-

ponding Society of Musical Sciences. In 1747, Bach presented the print of the Canonische Veränderungen über Vom Himmel hoch (BWV 769) as an obligatory annual gift for members, the Musikalisches Opfer (BWV 1079) for 1748 - the year in which the Credo from the Mass in B minor was presumably composed; the Kunst der Fuge (BWV 1080), which Bach was preparing to print at this time, was probably intended for 1749. All works with the highest standards of contrapuntal erudition and - with all due caution - an ideological character. In other words, in the almost hermetic world of counterpoint, which is at the same time led into radical harmonic condensations and consequences, a world view is manifested that is filled with a fundamental ordo idea, which owes itself to a conviction of creation that is deeply theologically founded. This requires justification.

The world of numbers as a link between the world and God

As Bach was an orthodox Lutheran, he was probably also familiar with the musical philosophy of St Augustine - Luther was an Augustinian monk. In Augustine, we therefore find significant references to Bach's typical treatment of theological questions, liturgical texts and piety-specific ideas in a musical idiom. In their search for biblically based guiding principles on the philosophical and theological quality of music, the Church Fathers usually referred to the Old Testament Book of Wisdom, where it says: "God has ordered everything by measure and number and weight" (Wis 11:20). Thus, for St Augustine, music as a sounding number (Pythagoras) is based on the eternal, purely spiritual number. In addition, it is a gift of divine providence and an expression of a pious heart's love of God. The soul is provoked to love God by the principle of numbers and order, which the soul loves in things: "Ad Dei amorem provocatur anima ex numerorum et ordinis ratione quam in rebus diligit" (De musica VI, cap. XII, 35).

The unity of the triune God is also reflected in the work of the Creator and therefore guarantees unity in all the diversity of worldly manifestations. This also applies to the individual itself, which is trinitarian in itself: being, life and understanding are triune in the Augustinian cogito. The Trinity of God is the guiding idea that grounds everything, because the three-step is found - in the words of Karl Jaspers - "in all things, in the soul, in every reality. The three-step in the thinking of everything that exists is an image of the Godhead". Augustine then also interprets the numbers psychologically, since "after the 'physical' numbers in the external object, they gradually lead upwards from the rhythms of the senses via the rhythms of memory to the bodily rhythms actively produced by the soul, such as breathing and heartbeat, to the rhythm of the judicium sensibile, which in turn is subject to the judgement of the spirit and the spiritual rhythms given to it by God", according to Hans Urs von Balthasar. However, this realisation of the number analogies takes place in the illuminatio through the light of God's absolute spirit. It is therefore understandable that bodily rhythms also resonate in the contemplation of divine things; all the more so will people feel the rhythms that animate the body full of joy in the visio beatifica after the resurrection (De musica 6, 49).

Balthasar summarises: "The harmony of God and the world exists on the basis of this relationship between the original numbers, which are represented in the being and essence of everything worldly ... it is even greater because even the infinite of God is not without measure, but is measured by the Son as the image of the Father, and because at this point the possibility and reality of a measured world arises in God."

Martin Luther valued the effect of music as recreatio cordis, renewal or refreshment of the heart and as purification from evil: "It is able to make the mind calm and cheerful, as a clear testimony that the devil, the author of sad worries and restless thoughts, flees from the voice of music almost as much as from the word of theology", wrote the reformer to the composer Ludwig Senfl in 1530. And in a sermon on Psalm 33:3, Luther stated that music "is the best refreshment for an afflicted person, through which the heart is again satisfied, refreshed and revitalised". He also saw the religious educational benefits of music ("If they don't sing it, they don't believe it") and regarded it as a fully valid form of praise to God: he himself wrote hymns, some completely new, some as translations of Latin texts into German, including corresponding adaptations of Gregorian melodies, which had liturgical status.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz transfers this philosophical-theological starting point to the compositional imagination when he speaks of music as "the secret arithmetical exercise of the unconsciously counting mind" in his Epistulae ad diversos in 1712. However, such an exercise of the mind presupposes the prior ordering of all elements and their relation to a fundamental organising principle. This becomes comprehensible in the concept of monads: "from the monad, the simple indivisible substance, the 'true atom of nature', the order of precedence rose via the central monad of the anima. Via the 'mens' to the 'ultima ratio rerum', to God. And just as the 'pre-stabilised harmony' holds this world structure together, so in the components of a fugue ... the microcosmic reflection of this 'pre-stabilised harmony' reigns as a meaningful and ornamental order ... in the laws of harmony and the contrapuntal theory of movements they (the Baroque composers, M.H.) allowed that metaphysical order to be reflected which for them was an order from God", according to Werner Korte.

The contemporary music theorist Andreas Werckmeister, whose instructions for tuning keyboard instruments aimed to create a tuning that would allow the piano to be played in all keys, provides one of the many examples of the conviction that was common in Bach's time that music was part of the divine order. Bach himself provided the corresponding proof with his Well-Tempered Clavier, using a Werckmeister tuning. Werckmeister wrote: "And even if this music received its power from God, it must have been arranged beforehand according to the natural order and principles that God has placed in nature. For God is a God of order. He will not confine his power to any disorder or confused being."

According to St James of Liège, resounding music is also the image and symbol of a supra-sonic harmony that is "based on a numerical ordo, on Proportio and Connexio". And Werckmeister again: the "numbers 1.2.3.4.5.6. and 8. (give) a corpus of complete harmony, and ... can depict for us in shadows the nature of the almighty God, as he has been from eternity in his eternal nature, before the foundation of the world was laid". The triad occupies a prominent position in this context. Like the three-part rhythm as tempus perfectum in the Middle Ages, it is also given a Trinitarian interpretation. The Alsatian theologian Johann Lippius sees in the triad "the image and shadow of that great mystery of the divine Trinity". Moreover, according to Werckmeister, "God (the Unity) is symbolised by 1, the Son of God Christ by 2, the Holy Spirit by 3, but all three are symbolised in the Trinity by the trias harmonica, the triad".

We learn more about the symbolic quality of the triad from Bach's contemporary, the Erfurt organist Johann Heinrich Buttstedt (1666-1727), from his work Ut mi sol re fa la, tota musica et harmonia aeterna. In the title, the major triad ut-mi-sol (c-e-g) is already related to eternal harmony. And Buttstedt explicitly sees this major triad as a tone symbol for the divine nature of Jesus Christ, while the minor triad re-fa-la (d-f-a) is interpreted as an expression of his human nature.

In his work Musicae mathematicae Hodogus curiosus, Andreas Werckmeister provides a number-theoretical justification for Bach's corresponding musical dispositions, especially in the B minor Mass: The trias harmonica perfecta, i.e. the major triad, has the proportions 4:5:6 (vibration ratios according to the natural tone series); the minor triad with its proportions 10:12:15 is considered a trias harmonica imperfecta, as it is further removed from the octave (1:2) understood as the perfect proportion, which in turn comes closest to the unity 1:1 = 1. Incidentally, the fifth, as a so-called dominant to the fundamental, is outstanding because it has the proportion 2:3. Werckmeister writes: "God himself is the unity". And the following applies to all created things - including musical ones: "The closer a thing is to unity, the more comprehensible, the further, the more imperfect and confused it is."

Musical parameters as an analogy of creation categories

Immanuel Kant proved the fundamental categories of space and time as the basis of any kind of world and self-knowledge. In music, analogous creative means can be found in abundance:

The spatial effect is concretised in the juxtaposition of high and low voices (soprano and alto versus tenor and bass in the vocal range; high and low strings or wind instruments; in turn, the variety of organ stops). Crescendo-decrescendo effects are perceived as distant or approaching sounds. Bright and dark sounds also produce spatial effects. The correlation of solo and tutti, instrumental and vocal as well as in mixed ensembles constitutes spatiality or mass. The distribution of individual choral and instrumental groups (cf. also the so-called Venetian polychoralism, Bach's double-choir motets or choral and orchestral arrangements such as in the St Matthew Passion) result in a choreography that is not only visually but also acoustically differentiated.

The perception of time comes into play in different ways:

- originally with the duration of the sound, i.e. its

commonality, - Time and rhythm as fundamental musical parameters organise music in its temporal sequence,

- by modifying the tempo - such as accelerando/ritardando, fermatas (actually suspension of the beat and interruption of the regular progression of time),

- The synchronicity becomes visually and acoustically perceptible in the overlapping of different bars (e.g. bars of 2 in one voice against simultaneously running bars of 3 in another); hemiolas as an interruption of the accents; phase shifts between voices that only come together again after several bars,

- and not least by taking breaks!

In addition, there is the category of the historicity of existence, which Kant did not consider. Of course, this also applies to the history of music and its various lines of development. Bach already showed an enormous thirst for knowledge in his school days when he copied Girolamo Frescobaldi's organ collection Fiori musicali from the library in Lüneburg, for example, or studied concerti by Antonio Vivaldi and French organ music by Nicolas de Grigny or Louis Marchand as well as French dance suites. He was also very interested in the classical vocal polyphony of the Dutch School and Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina. Many traces of this exploration and appropriation can be found everywhere in his own oeuvre.

Finally, in Bach's work, the overlapping of the profane and spiritual worlds must also be considered. Specifically, early Christian traditions are taken up, such as Bible texts, Bible paraphrases and liturgical texts such as the Credo, etc., and are soundtracked with advanced compositional means. Secular dance forms are integrated into sacred music due to the affective content of the dances. Symbolic connotations of instruments and musical figures are introduced: flutes as pastoral instruments, strings as noble or heavenly sources of sound - just think of the string accompaniment for the words of Jesus in the St Matthew Passion, they form a kind of halo around the head of Jesus. In addition, there is the assignment of certain notation styles to ideas of age and dignity, especially the old mensural notation when it comes to God the Father.

Finally, the area of the realisation of affects and emotions in musical figures must be considered. The relevant keyword is "musical rhetoric". To name just a few: Passus duriusculus (overly hard passage; chromatic tone sequence usually in the range of a fourth), suspiratio (sighing figures), hyperbolé (exaggeration: for example, when a scale exceeds the range of an octave in order to emphasise a word or (exaggeration: when a scale exceeds the range of an octave to emphasise a word or idea), repetitio (repetition of notes), chiasmus (X for Christ and therefore also a symbol of the cross), onomapoetry (the term itself contains a reference to the interpretation, such as a musical "cross" as a reference to crucifixion).

Now the definition of the Book of Wisdom quoted at the beginning regarding God's creative activity can be concretised with regard to its musical realisation:

- Musically, the forms and genres used in each case correspond to the measure; the change of emotions and moral attitudes conveyed in music and their ultimate resolution in harmony;

- The number corresponds to the number of voices, the intervals, the time and rhythm variations and their respective ratios; or geometric subtleties such as the application of the golden section for the internal ratio of triple fugues (cf. E flat major prelude from the so-called organ mass);

- The changing instrumentation, for example, corresponds to the weight: Solo and tutti, multiple choirs, echo effects etc.

Work analysis

The axially symmetrical arrangement with the crucifix in the centre

The Crucifixus forms the centre of the Credo setting. A choral movement (Et incarnatus - Et resurrexit), a solo aria or duet (Et in unum Dominum - Et in Spiritum Sanctum) and a pair of movements for choir a cappella and tutti choir (Credo in unum Deum/Patrem omnipotentem - Confiteor unum baptisma - Et exspecto resurrectionem) are symmetrically arranged around this movement, the fifth of a total of nine movements.

For Bach, the crucified Son of God incarnate clearly represents more than just one article of faith alongside others; for him personally, it is a source of support and hope. He not only allowed himself to be touched by the fate of Jesus, but also intellectually explored what Jesus' life, his humiliating walk to the cross, his death and resurrection had to do with himself, Johann Sebastian Bach. To paraphrase Paul Tillich: Jesus is the person who "absolutely concerns" the composer.

The three different musical levels are striking - and audible: The composition develops on the basis of the continuo, which is structured as a chaconne. The unchanged, recurring four-note sequence has something compelling in a negative sense and suggests an association with the hopelessness of the crucified, with the inexorability of torture; the inevitability of death is palpable here. At the same time, the sequence of notes forms a passage duriusculus: going to the cross is associated with unbearable pain.

Its twelvefold appearance is very important and by no means a coincidence. As in Baroque art, the number 12 symbolises the completion of a period of time, a task, a structure: 12 months, 12 tribes of Israel, 12 apostles, 12 gates of the new Jerusalem. An old folk song also says: "Twelve, that is the goal of time, man, consider eternity". This shows that With the death of Jesus, time is fulfilled - not just his own earthly lifetime. Through his death on the cross and the subsequent resurrection, the earthly eon with its darkness and wickedness has also come to an end; the power of the devil (for which there is a separate musical term: the augmented fourth Diabolus in musica) has been definitively broken. The new eon begins with the resurrection of Jesus: Heaven - and thus the timelessness of eternity - is basically open to everyone.

Bach allows this hope to shine through in an incomparable way by intoning a 13th development of the chaconne theme, but turning it off in the middle and redirecting the movement, which is in E minor, to the parallel major key of G major. The flutes and strings accompanying the movement are silent. Bach also prescribes piano. Both depict the peace of the grave in et sepultus est. The flutes and strings have formed the second level by constantly playing sighing figures (suspiratio) or introducing excessive onomapoeia (excess of suffering) or diminished triads (bars 8, 20, 26; with the tritone as diabolus in musica) or invocationes (invocations: upward leaps of sixths). Incidentally, flutes are also used in the drooling cries of the crowd in Bach's Passions.

The third level is formed by the vocal parts, which are led downwards in bars 5 to 12 (catabasis) and also sing sighing figures. These are emphasised, as it were, by Bach's very rarely indicated bow lines, which result in a lamenting motif. This Crucifixus movement is the centre of an axial construction. In his 1747 organ work Kanonische Veränderungen über Vom Himmel hoch, Bach also changed the original version and placed the variation that first concludes the cycle in the centre of the work, around which the variations are again grouped axially symmetrically. Axial symmetry can also be found in his St John Passion, centred around the chorale Durch dein Gefängnis Gottes Sohn ist uns die Freiheit kommen. The chorale Mit Fried und Freud fahr ich dahin occupies a similar position in the Art of Fugue. In each case, the incarnate and suffering but resurrected Son of God Jesus Christ is at the centre of the reflections and musical meditation. Bach already used this method in the seven-part Laudamus te of the Gloria of the Mass in B minor. Here, too, the crucified, humiliated Son of God is at the centre, around whom six movements are symmetrically grouped. Walter Blankenburg characterises this Qui tollis peccata mundi "as a humbly imploring turning to the Crucified One".

The remaining sentences at a glance

Now to the introductory Credo in unum Deum (1st movement of the Credo) and the 2nd movement Patrem omnipotentem, factorem coeli et terrae, visibilium omnium et invisibilium. God the Father, the Creator God, speaks according to the first book of Moses, Genesis, his word and creation lifts up: This is why the tenor alone - accompanied only by the continuo - begins Credo in unum Deum. The Word of Creation, which initiates the history of the world and the cosmos, is performed by the same voice that in Bach's passions, oratorios and cantatas presents the Good News of the Gospel, i.e. the Word of Redemption. The Evangelist's recitatives are always performed by the tenor; in other words, the Word of Creation and the Word of Salvation come from the same divine source.

The movement itself is conceived in a visually antiquated manner: as an alla breve (as in classical vocal polyphony). The clefs are to be understood in the same way as the depiction of God the Father with a beard in the visual arts. Bach demonstrates the reference to music history and thus also to the tradition of the liturgy across denominational boundaries by using an ancient Gregorian melody for the Credo setting.

The continuo does not begin at the same time as the tenor, but a quarter note later: God utters his word of creation and time and space immediately come into existence: right at the beginning, the continuo part runs through a complete octave, eight notes, called diapason, which means going through the whole, suggesting the whole of creation. The movement is driven forward without pauses in continuous crotchets. Like clockwork, creation runs towards its goal under the care of God the Father. The continuo runs through two full octaves in toto, an expression of the greatness and grandeur of the work of creation. Only in the last bar does the movement end in two whole notes. The entire movement is a seven-part fugue (performed by two violins and five choral voices), completely stringent, without interludes. The head motif consists of seven syllables, the first bar of the basso continuo comprises seven descending notes: God leans towards his creation. Seven as a divine number: it stands for the perfection of a whole, especially for the divine structure of earthly things, from the seven-day work of creation, to the division of the festive calendar, to the seven miracles and "I am" (ego eimi) self-testimonies of Jesus in the Gospel of John.

The following events bring into play the variety of elements of creation from the visible to the invisible: trumpets, timpani, oboes, five-part choir, a magnificent hymn to the Creator who made and rules heaven and earth. Bach invents an eloquent vocal figure for this context: factorem coeli et terrae begins in the highest register of each voice and runs downwards through one and a half octaves: God turns from heaven to his creation on earth. At the end of the 2nd movement, Bach makes a completely surprising notation in his autograph score: 84 bars! In other words, the product of 7 and 12, hinting at the completion of the entire divine plan: both the history of the cosmos and the history of salvation lie solely in God's hands and therefore (hence the festive jubilation of this movement) also reach their goal in God!

The setting of the second article of faith dedicated to the Son of God begins with movement 3 Et in unum Dominum Jesum Christum. The soprano and alto duet is accompanied by strings, two oboes d'amore (the so-called oboe of love) and basso continuo (basso continuo). Bach chooses a canon as the form, which enables the closest connection between two voices. The symbolic content is immediately apparent: father and son are closely connected. The Son (who is assigned the second voice) follows at the interval of a crotchet, meaning that the Father is the origin of the Son. The sameness of the theme musically testifies to the unity of essence. However, Bach's meticulous phrasing of the instrumental canon preceding the vocal parts differentiates the uniform tonal material in the rendition: the last two quavers (4th and 5th notes) of the motif are articulated in the upper voice in a struck manner, but are played legato in the following lower voice. This symbolises the difference and reality of the characters. This is also emphasised by the change of imitation intervals, which indicates the relative independence of the voices. To the words descendit de coelis, the strings intonate a striking downward movement spanning up to two octaves.

The fourth movement Et incarnatus est is clearly organised in three levels: The two violins permeate the entire movement with an unmistakable melodic phrase consisting of five notes, with notes 2 to 4 (two upward groups of quavers) forming the so-called chiasmus: If you connect the two outer and two inner notes with a line, the result is a horizontal cross, in the form of the letter X, which stands for Christ (the Greek Chi as the first letter of the name). If the first note is added, then the notes 1, 3 and 5 form a minor triad, which we have seen in Buttstedt and others as an expression of the human nature of the Logos, but here additionally as a downward sequence of notes, in which the fate of Jesus' life, his suffering and death, are associated in this context. The entire figure is in B minor, the parallel key of D major, which in turn refers to the Logos with its two crosses (in the St John Passion, the same pitch - namely the transition from a lower to a lower octave - is used for the words: "It is finished". The Praeludium and Fugue in B minor for organ (BWV 544), which refers to this passage, uses the same sequence of notes and is thus recognisable as Passion music). In the last five bars, the basso continuo also adopts this motif and takes it down one and a half octaves to the words et homo factus est: the Saviour has arrived in the world, will pass through the whole of creation and lead it out again into the divine light. Here we can already think of the words: descended into the realm of death.

The introductory repetition on one and the same note, which appears again on the dominant in bars 20 to 27, is particularly striking: B and F sharp are heard 24 times each. 24 as the number of the hours of the day is a reference to the fullness of time, or in other words: time is fulfilled. This is how Bach interpreted this number in his cantata "Liebster Gott, wann werd ich sterben" (BWV 8), as Walter Blankenburg points out. The theme of the chorus in turn consists directly of the descending B minor triad and emphasises the kenosis, the humiliation of the Son of God.

After the Cruzifixus, a choral movement (movement 6) appears again in axial symmetry, but this time in a completely different mood and compositional style: Et resurrexit pulls out all the stops and overwhelms the senses after the standstill of et sepultus est. Now, however, the entire orchestra and the choir, which is actually conducted in five voices, jubilate in the tempus perfectum, the triple metre, in D major. The central melody in response to the text is again structured axially symmetrically: From the triplets of the second bar, it returns in mirror image to the starting note a'. The slight rhythmic variation (two quarter notes instead of two quavers) is an indication of the newness that dawns in the resurrection: the same Jesus Christ, but in the new aeon (now in the end-time phase; time does not continue in a linear fashion, but has a new quality).

After the first short instrumental interlude, the resurrection is musically presented in a highly sensual manner from bar 9 to soprano 1. The soprano reaches the top note b'', which is otherwise only reached once more in the entire mass, in the Gloria on the word excelsis (bar 94). The meaning is clear: the crucified and risen Jesus has returned to his almighty Father in the heavens and has since been enthroned in heaven as the person of the Trinity himself, preparing a heavenly home for his own. A fundamental mystery of the Christian faith is revealed here: Christ has taken human nature into heaven with him. This shows the true nature of the Trinity: the loving care of the divine persons towards each other and towards the creatures. This is also illustrated by the recurring triplet figure in the theme.

The close interweaving of heaven and earth as a result of Jesus' resurrection, which also triggers joy and praise from the angels in heaven, is audible in the expansive instrumental writing: of the 131 bars of this movement, 55 bars are purely instrumental music. Walter Blankenburg explains: "These by no means only have a structuring function, but are intended to symbolise the heavenly world in connection with the statements of faith about the resurrection, ascension and return of Christ, to represent a heavenly concert, as it were." The continuo bass plays the upward major triad as an indication of the divine nature of Jesus Christ. Just one more detail: in the bass in the Et iterum, for example, the expansive and time-spanning judgement of the Risen Christ can be heard very well in the words vivos et mortuos, which span almost two octaves (e' to F sharp).

The third article of faith relating to the Holy Spirit is introduced with the Et in Spiritum Sanctum (movement 7). The bass aria plays with the number three in various ways. The key is A major, i.e. three "crosses". However, there is always a hidden reference to the second divine person, Christ, the Logos. Firstly in the choice of time signature: 6/8 means two counting times or, for the conductors, beat times. Then, of course, in the choice of a bass and not a high female voice as is usually the case. The intention here is that Bach also chooses the bass voice for the person of Jesus in the Passions and cantatas. This means that the Holy Spirit is the one promised by Jesus to his disciples in the Upper Room; it is the Spirit of Jesus who is present and at the same time the Spirit of the Father. This emphasis on the second divine person becomes understandable against the background of the disputes about the "Filioque" before and at the Council of Nicaea (the Credo in Bach is entitled Symbolum Nicenum).

The Holy Spirit emanates from the Father and the Son. This can be heard very clearly in bars 43 to 45, where the bass ex patre Filioque procedit proclaims the Son's involvement in the "Processio" of the Holy Spirit in an almost erupting melody from C sharp to E', i.e. spanning a decimal (which is to be interpreted as a figure of hyperbolé, an exaggeration). The whole piece also subtly introduces the Father: All three text sections (Et in Spiritum sanctum; Qui cum Patre et Filio adoratur; Et in unam sanctam catholicam) are opened on the first with the continuo; the bass soloist enters on the second.

There are three soloists, with two oboes d'amore playing alongside the bass; they begin simultaneously, but the second oboe always plays a fourth or third lower. However, they usually begin half a bar apart; oboe 1 always begins, which can be interpreted as the closest connection between father and son, with the father taking precedence.

The penultimate movement Confiteor unum baptisma in remissionem peccatorum is - symmetrically referring to the beginning of the Credo - an a cappella movement, accompanied only by the continuo. Again alla breve, and referring to old Dutch compositional techniques (classical vocal polyphony) both in the movement pattern and in the texture: the movement begins with imitation pairs of soprano I and II as well as alto and tenor. The bass is, so to speak, supernumerary. It is given special tasks, such as the upward passage duriusculus in bars 64 to 66 as a reference to overcoming sin. The fundamental importance of baptism as the original sacrament of the church and of salvation is thus emphasised, especially as the command to baptise goes back to Jesus himself. Baptism therefore refers back to the origins of the church; "old" compositional techniques and recourse to Gregorian melodies are appropriate here. And logically, it is the bass who, in bars 73 to 87, takes up the early church Gregorian melody already quoted at the beginning of the Credo in unum Deum. The tenor emphatically emphasises the message of the necessity of baptism for the forgiveness of sins by taking over the cantus firmus from the bass and performing it in double note values (bars 92 to 117).

The sensitive listener is seized by an almost mystical shiver at the transition from this movement to the concluding ninth movement Et expecto resurrectionem mortuorum, et vitam venturi saeculi. Amen. The movement suddenly builds up in bar 121 as Bach introduces an adagio, while at the same time the continuo moves into regular, repeated crotchets (cf. Crucifixus). In addition, Et expecto resurrectionem mortuorem is already declaimed as an anticipation of the last movement. This transitional passage takes up exactly 24 bars: The fullness of time has come, the counting of hours has been exhausted, as the 24 hours of a day have become obsolete with the Last Day, the day of judgement by the Son of God (Michelangelo's "Last Judgement" in the Sistina comes to mind). For with the resurrection, everything becomes new, everything is transformed. Suffering, guilt and death are condemned and overcome, the new aeon, the age of the redeemed has dawned. It is precisely this phase of transformation that these 24 bars indicate in an unprecedented way, with harmonies that are extreme even for Bach: a chain of dissonances that are only temporarily resolved show an event that surges back and forth, striving towards a final harmonic resolution. In this way, bars 137 to 140 mark the transition into the new world, in that after compact five-part harmony, only the soprano 1 rises and introduces a C sharp major chord (far away in the circle of fifths) in bar 139 with the enharmonic reinterpretation (= transformation) from C to His.

Then, with Vivace e Allegro in quadruple tempo, the resurrection jubilation breaks in, performed by all instruments and choral voices. The respective tutti entries of the choir are always characterised by ascending broken major triads, the triad harmonica perfecta. The movement is in the main key of D major (also the main key of the Christmas Oratorio) and refers to the second divine person, whose resurrection makes the resurrection of each individual human being ontologically possible. This Christological basis of the praise of the Trinity that runs through the entire movement also emphasises the choice of duple time instead of triple time.

The exuberant jubilation is briefly interrupted by the final words of the Credo et vitam venturi saeculi. The movement rebuilds itself in a narrowing of the vocal parts in order to enter into an increasingly flowing movement at the Amen. In bar 77 ff., trumpet 1 introduces a three-note sequence three times (reminiscent of the Gregorian Kyrie), interrupted by a significantly placed E minor triad (as a reminiscence of the human nature of the Logos), followed by a D major triad as a signal of the divine nature of the Logos.

With the concluding Amen fugato, which quickly sweeps all the voices into a forward-rushing eighth-note texture, the Credo reaches its brilliant conclusion, which bursts in like a flash without ritardando and without any further rhythmic or harmonic intricacies: everything has been said - the future is open into the glory of God.