While the numbers of people leaving the church in the dioceses of the German-speaking world are skyrocketing these days and one record number of people leaving is chasing another, Luke's Acts of the Apostles, to which the following reflections are dedicated, tells of numbers that are similarly skyrocketing - but of conversions, baptisms and the associated entries into the Jesus movement: Shortly after Jesus' ascension, 3,000 Jerusalemites become part of the Jesus movement in one fell swoop (Acts 2:41). And in the narrated world just a few moments later, thousands more join (Acts 4:4, 17; 5:28). In Acts 6:7, Luke notes that even a large number of temple priests confess Jesus as the Messiah and thus join the Jesus movement. And so it goes on and on. In the form of figures such as Philip, Barnabas and Paul, the Jesus movement travelled through the ancient Mediterranean region with proverbial seven-league boots and spread from Jerusalem via Judea and Samaria, especially to the west (cf. Acts 1:8) - with the long-term goal of Rome, the capital of the empire, which was reached in Acts 28, meaning that Christianity had finally arrived on the world stage. Christianity finds massive followers in many individual places. Why is that? What makes the Jesus movement an attractive offer on the ancient market of religious, spiritual, ethical and philosophical concepts in the world narrated and always staged by Luke, behind which, of course, historical experiences also emerge?

Just as the reasons for leaving the church today are many and varied and are certainly not fuelled solely by the abuse crisis and a backlog of reforms, the reasons Luke gives for joining the Jesus movement are also many and varied. Luke mentions some of them as particularly important, almost in a tone of conviction, while others are more visible between the lines, but were possibly decisive for the outstanding success of the Jesus movement. Following sociological considerations to explain migration processes, a distinction can be made between pull and push factors. While pull factors refer to those moments and characteristics that have an attractive effect and positively encourage migration (for example, in the sense of setting off for the "Promised Land"), push factors are those aspects that trigger migration pressure, i.e. that make people experience a previous situation as deficient (comparable to the departure from "the slave house of Egypt") and force them to search for a better future.

This model can be applied to the Acts of the Apostles and the historically tangible success of the Jesus movement narrated in it. This is because the narrated entries into the Jesus movement are forms of mental or spiritual migration, which - as will be shown - also contain elements of cultural, political and social migration: After all, those to whom the Jesus messengers address their message of seeing in Jesus the Messiah of God, of following his convictions and maxims of life, and above all his vision of the dawning kingdom of God, are already religiously and culturally moulded people, be they people of the Jewish faith or pagans, who have a religious and cultural home beyond the Jesus movement and who leave this home behind, at least in part, when they join the Jesus movement. This article asks what, from the perspective of the Acts of the Apostles, triggers their "mental migration" and leads them into the Jesus movement, i.e. what made the early Christian faith attractive. Firstly, aspects clearly mentioned in Acts as pull factors will be considered. It is then necessary to reflect briefly on potential push factors in the world narrated by Luke, before concluding by addressing pull factors that operate more in the "background of the narrative", which also have decidedly social and cultural-historical implications.

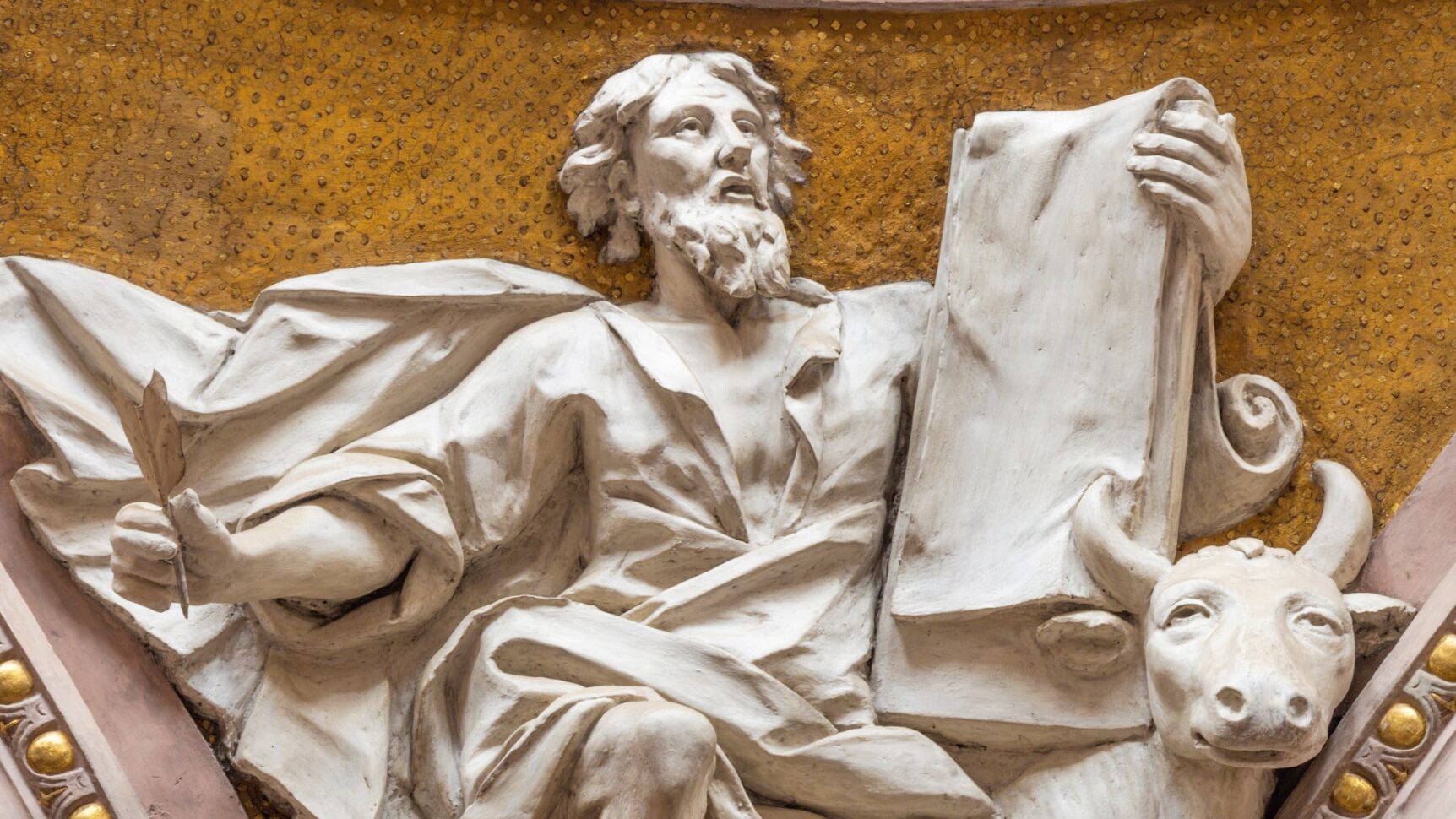

Frank proclamation, miracles and the work of God

From the perspective of Luke's narrative, one factor is particularly decisive for the attractiveness of the Jesus movement, at least in quantitative terms: this is the convincing proclamation of the Christian message of salvation through the speeches of equally convincing messengers of Jesus (the Acts of the Apostles no longer knows of women messengers of Jesus who give longer speeches). Again and again Luke tells us that people turn to the Jesus movement individually, in small groups or in droves in response to a proclamation speech (cf. Acts 2:14-41; 3:11-4:4, 17; 5:42-6:1; 8:4-13; 8:26-40; 11:19-24; 13:14-52; 14:1-7; 14:20b-21; 16:11-15; 17:1-4; 17:10-12; 17:16-34; 18:1-11; 19:1-40).

For Luke, this proclamation is characterised by boldness (parrēsia) (cf. Acts 2:29; 4:13, 29, 31; 9:27, 28; 13:46; 14:3; 18:26; 19:8; 26:26; 28:31). This refers to undisguised, open speech that is authentic, that does not take false considerations and would be insincere, that does not ventilate empty speech bubbles or rely on rhetorical tricks of persuasion. The keyword parrēsia frames almost the entire proclamation narrated in the Acts of the Apostles like a leitmotif. Peter proclaims with parrēsia at Pentecost (Acts 2:29; 4:13) and Paul also proclaims with parrēsia in the last verse of Acts and thus at the end of the narrated world in Rome (Acts 28:31). Anyone who speaks like Peter or Paul in Luke also appears to be a credible, authentic witness for Jesus.

Such authentic proclamation, which does not use empty theological formulas, worn-out metaphors and anaemic language, but proclaims creatively, in a situation-specific and addressee-orientated way, is a real pull factor for Luke. It attracts - precisely because it is not so concerned with the orthodoxy of words and endeavours to proclaim the whole truth of Christianity, but instead spends energy on how the core of Jesus' message can be translated into different situations in an accessible way. In this sense, it is striking how Luke's narrative figures in the proclamation of the word are so distinctly situational and contextually appropriate: In front of a Jewish socialised audience, such as that encountered in Peter's sermon on Pentecost in Jerusalem in Acts 2:14-36 or in the synagogue in Pisidian Antioch (Acts 13:16-41), where Paul speaks, the proclamation is in part clearly Christological, because the common basis between the messenger of Jesus and the addressees, faith in the one God, is not up for discussion or needs to be justified. In these cases, the role and dignity of Jesus is much more in the foreground and the fact that Jesus really is the Messiah of God awaited by Judaism is justified with recourse to often quotable, well-rehearsed biblical-Jewish traditions. In contrast, things are much less Christological in Lystra (Acts 14:8-18), for example, where Barnabas and Paul speak to a non-Jewish audience about the one God as Creator, themselves as creatures and the possibility of natural knowledge of God. Jesus is never mentioned. For Luke, all of this is preaching characterised by parrēsia in the mouths of people who appear authentic - and this combination is attractive.

The miracles and miraculous signs that occur through Jesus' messengers and in the context of the Jesus movement can undoubtedly also have an attractive effect. In this perspective, following Jesus also means imitating Jesus, who also appears as a miracle worker in the Gospel of Luke. However - and this is striking - experienced miracles are only very rarely the explicit and sole trigger for joining the Jesus movement (if I read correctly, this is only the case in Acts 9:32-35, 36-43). Although they are spectacular, they require commentary through proclamation in order to have a "successful" effect. This becomes particularly clear in the long narrative arc of Acts 3:1-4:22. While the people of Jerusalem react to the public healing miracle of Acts 3:1-8 with fascination, amazement and also horror (v. 10), but there is no mention of even one follower being won over, Peter's subsequent speech commenting on the miracle (Acts 3:11-26) actually catches on and is a reason for many in Jerusalem to become believers and part of the Jesus movement (cf. Acts 4:5).

This pattern of miracle and commentary proclamation (or proclamation and subsequent miracle) is found several times in the Acts of the Apostles (cf. Acts 2:1-43; 5:12-16; 8:4-13; 16:17-34; 19:1-12). Here, too, it is the proclamation of the word that is explicitly characterised as attractive and successful. Just how necessary this commenting proclamation is and how double-edged the working of miracles can become becomes clear in Acts 14:8-20. Here, the people of Lystra thoroughly misunderstand the healing miracles performed by Barnabas and Paul. They think that the two are gods in human form, a misconception that the two initially struggle to correct in their preaching, but ultimately succeed. For them, God is of course at work when miracles happen.

Of course, it is not only behind the miracles that Luke recognises the work of the one God and his Messiah (cf. also Acts 3:6), so that it cannot and must not be a question of focusing on all the miracles.s miracle workers as powerful and worthy of reverence - this topic and the temptation of power associated with it is also clearly dealt with in Acts 8:4-25 in addition to Acts 14:8-20 - Luke also generally recognises the work of God and his Spirit behind the growth of the Jesus movement itself. This undoubtedly also applies to the proclamation of the word, because the ability to speak freely (parrēsia) is, according to Acts 4:29.31, a gift from God, a charism that the Jesus community can ask God for. And so God is ultimately at work when people find their way into the Jesus movement (cf. very explicitly Acts 2:47; 9:31).

Virtually absent: push factors

As explicitly as Luke names pull factors that make the Jesus movement appear attractive in his narrative perspective, potential push factors remain unclear. If one reads the Acts of the Apostles to see whether narrative figures characterised as non-Christian formulate explicit deficits with regard to their pre-Christian religious socialisation, it is noticeable that this is only very rarely the case. Only one character actually formulates a genuine religious deficiency, or more precisely a lack of knowledge: the Ethiopian eunuch in Acts 8:26-40, who reads the prophetic writing of Isaiah but does not understand it and recognises this as a deficiency because no one has ever taught him to understand this writing (v. 31). You could say: he lacks an exegete ... In Luke's narrative world, Philip then takes on this role. This lack of knowledge, which the eunuch actually perceives as a lack and communicates accordingly, ultimately leads him into the Jesus movement, as the narrative leads to the baptism of the Ethiopian (v. 38).

The lack of bodily integrity and healing that acts as a trigger in the healing stories is also not named as an explicit push factor in the Acts of the Apostles. With regard to the healing stories told in the Acts of the Apostles, it can be noted that the sick and marginalised obviously do not find healing within the framework of their pagan or Jewish lifeworld and that there is a deficit here that is satisfied by the mediation of Jesus' messengers. This contrast is particularly striking with regard to the paralysed man in Acts 3:1-10, who always sits at the Beautiful Gate of the temple area and thus on the edge of the presence of God believed in Judaism. However, he has not been physically healed there for years and years. He always remains in front of the actual temple area and asks for alms there. He only finds healing in this place when he encounters Jesus' messengers in the form of Peter and John, who promise him healing in the name of Jesus. And only then can he himself find his way into the temple area (v. 8), so that from a spatial-semantic perspective, only the healing by Christ opens the way for him into the house of God. Strangely enough, however, in the more widely told healing stories in the Acts of the Apostles (the case is somewhat different in the Healing Summaries), those to be healed only very rarely ask for healing themselves. The paralysed man in Acts 3 does not do this at any point either, but asks the apostles for a monetary donation - and receives much more than this. Even from this perspective, the sick and marginalised do not experience their deficient condition as a religion-related deficit that they would actively seek satisfaction from the Jesus movement.

In contrast, it is somewhat more common for followers of Jesus to point out religious deficits in pagan and non-Christian Jewish religiosity in their preaching. This applies to Paul in Athens, for example, who according to Acts 17:22f. attests to his pagan audience that they were characterised by a kind of blindness with regard to true monotheism. They would ignorantly worship what Paul would clearly proclaim to them: the one God of Israel, who was only "an unknown God" (v. 23) to them. With regard to Judaism, which does not believe in Christ, religious deficits are then highlighted by Stephen, Peter and Paul, such as the lack of knowledge of Jesus as the Messiah or the soteriological deficits that Paul complains about in Antioch (Acts 13:38f.): True salvation, righteousness before God and forgiveness of sins do not arise from the law, but through Jesus.

An overview of this field of narrated and possible further push factors gives the overall impression that Luke does not actually emphasise the attractiveness of Christianity at the expense of pagan or non-Christian Jewish religiosity. To put it pointedly: It is not the others who are bad and deficient, but the Jesus movement is incomparably good and attractive in its own right. And very tangible social, cultural and ultimately also monetary factors also contribute to this attractiveness of the Jesus movement, which become particularly apparent when one compares the Jesus movement with Jewish synagogue communities and cult and professional associations in the Greco-Roman environment. The New Testament scholar Eva Ebel has analysed decisive material on this in her study "The attractiveness of early Christian communities".

Open doors, no entrance fees, weekly meals and more

If we read the Acts of the Apostles in terms of how the figures who appear in it as members of the Jesus movement are characterised, then we get the impression that Jesus' communities were open to the entire spectrum of ancient society. In addition to men, there are of course also women (e.g. Acts 16:14), alongside Jews there are also non-Jews (Acts 8/10-15), there are proselytes and God-fearers (Acts 6:5; 10:2; more on this in a moment), alongside the rich (Acts 18:7) there are also many poor (such as the widows of Acts 6:1-7), alongside the old there are young (Acts 20:9; 21:16) and alongside long-established Hebrew speakers there is also room for newcomers who speak Greek (Acts 6:1), and even social outsiders such as the eunuch of Acts 8:26-40 are fully welcome (and of course slaves can also become members of the Jesus movement, as the Pauline letters show). Everyone has a place in the Jesus movement, as long as they share the basic convictions of the group. No one is excluded because of their economic power, their gender, their ethnicity, their education, their age, the constitution of their body (especially their sexual organs) or their social and legal status. This distinguishes the Jesus group from all forms of pagan cult and professional organisations or Jewish synagogue communities. In the Jesus movement, the entire spectrum of ancient society is welcome and everyone can become a full member with (at least initially) equal opportunities for development. This is an attraction factor that should by no means be underestimated, which Luke, of course, fully implies.

The Jesus movement is of particular interest to the group of God-fearers mentioned above for a very specific reason, which is particularly evident in the Acts of the Apostles. The term "God-fearers" refers to non-Jewish people (women and men) in the neighbourhood of diaspora synagogues, who generally belonged to the local elite, were financially powerful and supported the synagogues materially, attended the services, were attracted by Jewish monotheism and its ethics of the good life, but did not convert and become part of the congregations and the Jewish people of God as proselytes, because such a conversion would have implied tangible disadvantages for them. Jewish synagogue communities kept these God-fearers at a certain distance, despite all their sympathy: anyone who wanted to belong fully to the synagogue and thus to the people of God had to actually enter Judaism, be circumcised as a man and observe all the applicable commandments and prohibitions of the Torah and other traditions in order to obtain the status of proselyte.

According to the testimony of the Acts of the Apostles (cf. above all Acts 15), the Jesus movement takes a different path here. Anyone who wants to become a member, believes in the one God, sees the Messiah in Jesus and wants to follow his vision of the good life and thus, according to the self-image of the Jesus movement, naturally also becomes part of the Jewish people of God, does not have to be humble, does not have to keep the entirety of the Mosaic Law, but only has to observe the clauses of St James, i.e. essentially keep a few dietary commandments (cf. Acts 15:20). This is an attractive offer, especially for the God-fearing. Through innovative entry conditions and entry rituals (in addition to circumcision, baptism is an entry ritual into the people of God), they can become full members of a Jesus synagogue, thereby participating in Jewish traditions and being part of the people of God without having to be circumcised, which was considered unseemly in Greco-Roman culture. According to the self-image of the Jesus movement, God-fearing people therefore receive the same offer in a Jesus synagogue as in a non-Christian Jewish synagogue - only on better terms. This offer has an attractive effect and so there are a great many GThe early members of the churches (cf. Acts 10:2, 22; 13:16, 26, 50; 16:14; 17:4, 17; 18:7) were among the addressees of Jesus' messengers who feared God.

If we then look at the rather small group of potential members of the Jesus movement, other implicitly narrated pull factors become relevant. The fact that membership of the Jesus movement was initially free of charge contributes to the attractiveness of the Jesus movement with regard to this group. In contrast to the vast majority of associations in the Greco-Roman environment, no entry or membership fee was charged. Even those who belonged to the destitute were welcome; indeed, the Jesus movement was particularly attractive to them in Luke's depiction. This is because it was characterised by the high ideals of a community of goods and justice based on need. Texts such as Acts 2:44-47; 4:32-37 and 6:1-7 tell us about this. Those who had greater material goods in the community were invited (but not obliged, cf. Acts 5:1-11; community of goods is not based on coercion and expropriation) to share their goods with those who had less. And in the narrated world, many of the first followers of Jesus embraced this new social reality. In other words, from Luke's point of view, the social inhomogeneity of the communities resulting from the open community doors is not a disadvantage for the Jesus movement that leads to insoluble conflicts, but on the contrary is an advantage that needs to be shaped in the spirit of Jesus.

Of course, these are Lucanian idealisations, as the conflict over Hananias and Sapphira (Acts 5:1-11) or the Jerusalem dispute over the provision for widows in Acts 6:1-7 show. However, the latter text in particular makes it clear what creativity the early Jesus movement displayed in Luke's view in order to really live the community of goods in practice and to be able to realise the social flow of money. The Jerusalem church quickly establishes a community of goods together with the apostles - the circle of twelve and the entire church of men and women work hand in hand in a participatory manner and share leadership, power and responsibility, according to Acts 6:2-6: Incidentally, this is also definitely an attraction factor, because joining the Jesus movement allows people of different genders and social status to take part in participatory processes and thus brings with it room for manoeuvre and a gain in autonomy; the Jesus group thus also offers opportunities for development for those who tend to have fewer options for action in Jewish synagogue communities, in the Jewish temple cult, in pagan associations or in pagan religious practices - a new committee, the seven table servants, to resolve the conflicts over the widows' provision. Structures are thus adapted to needs and ministries should resolve conflicts and not themselves become the bone of contention. The fact that Luke frames this exemplary conflict resolution with two growth notes with a view to the Jerusalem church (vv. 1.7) speaks for itself: the common conflict resolution is also to be a source of inspiration.The participatory solution, which serves the ideal of justice and care for the poor, has an attractive effect. In this sense, too, inhomogeneity is an advantage and contributes to the growth of the movement.

A special form of communion of goods then also characterises the weekly Lord's Supper or Eucharist celebrations of the early churches. In the churches of the Acts of the Apostles, bread is also broken together (cf. Acts 2:42.46; 20:7.11). Unfortunately, Luke does not tell us exactly how this took place in early Christianity. We have to rely on support from the world of Paul's letters, parts of which also address the churches that Luke tells us about in Acts. From 1 Cor 11:17-34, for example, we know that not only bread and wine were shared at the Lord's Supper in the church of Corinth (cf. Acts 18), but also other foods. At its beginnings, the Lord's Supper still forms a tense unity of sacred meal and meal of satiation, in which not only vertical communion with the heavenly Jesus through the breaking of the one bread is aimed at, but also an earthly-horizontal communion through the sharing of the food brought along. According to the ideal, everyone should be satisfied by sharing the food, which is an attractive factor for poorer members of the congregation in particular, as their everyday lives are often characterised by growling stomachs. At least at the Lord's Supper, however, the poor should also be able to be properly filled (which goes completely wrong in Corinth and provides the reason for 1 Cor 11:17-34). The intensity of the communal meal celebrations (frequency, distribution rules) is higher than in comparable pagan associations, for example, which once again made the Jesus movement more attractive to the little people of ancient society - even in the here and now of their concrete lives.

After all, as part of the Jesus movement, you are a member of an expanding network. As the Acts of the Apostles discreetly tells us, this is particularly advantageous when travelling. Because as a Christian, you also have friends in a foreign country if there is already a Jesus group there. Then you can be a guest in someone else's house, as Acts 21:15f. tells us with regard to the Cypriot Mnason. In the Acts of the Apostles, private homes increasingly function as church houses, which are open to both local church members and travelling sisters and brothers. This also makes the early Christian faith and life in a Jesus community attractive.

Believe differently - live differently

In addition to genuinely spiritual-religious attraction factors, which are part of the core beliefs and brand of a monotheistic religion of salvation, in addition to the authentic proclamation of a credible message of salvation by equally credible preachers, tangible social and cultural-historical factors also had an attractive effect, which gave the early Jesus movement an advantage over Jewish synagogue communities or even pagan associations. It is therefore also the innovative power of the early Jesus movement that The first Christians believed differently and therefore also lived differently in practice in order to be authentic. The first Christians believed differently and therefore also lived differently in practice in order to be authentic: they opened the doors of the churches wide - and everyone was welcome. They share the goods of life - even with marginalised people. They created new structures at certain points - and allowed many to participate.

There is no question that these implicit pull factors are not equally attractive to everyone. The social attractiveness factors in particular tend to target the little people. However, those who belong to the rich and powerful in ancient society may even perceive these social factors as a hurdle, because they are suddenly no longer just at the table with their peers, but with others, and are invited to share their wealth. There must have been such idealists, because otherwise the Lucanian ideal of community of goods and justice of needs would really only remain a beautiful illusion. In quantitative terms, however, the number of wealthy people in the early churches will have been small in comparison to the relatively poor, as Paul also states with regard to his Corinthian church, for example, noting that there were not many powerful and high-born people in their ranks (cf. 1 Cor 1:26). This is different today in many respects - which brings us back to the beginning.

To counter the current wave of departures, the Acts of the Apostles certainly offers nony patent remedies. Even against the background of a changed social structure in the Christian communities of the present day, as well as with a view to our current living environment, which cannot be easily compared with the ancient environment of early Christianity, it would be a biblical fallacy to try to counter the current wave of departures that is gripping our churches by focussing on the pull factors directly and indirectly narrated by Luke and simply transferring the church of the beginnings to our time. Of course, we can also learn from the Acts of the Apostles for the present day that the Jesus movement at its beginnings was also highly attractive because the churches had the courage to inculturate the message of Jesus with a view to their concrete environment and the people in their living environment and to put it into practice in such a way that it was understandable on the one hand and, on the other, actually made an offer for a better life in the here and now, i.e. responded to the requirements and signs of the times. This is also a lasting obligation for the church of our day in the face of turbulent times and profound processes of upheaval.