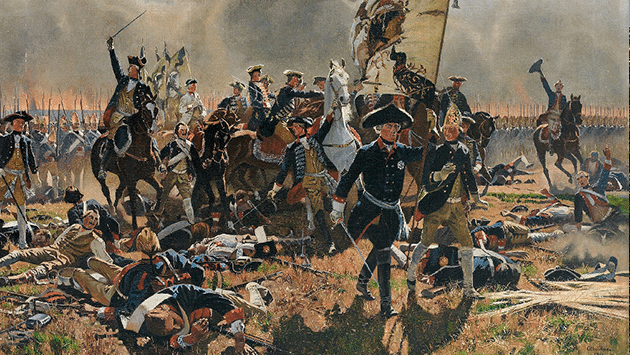

In January 1763, Johann Christoph Stockhausen (1725-1784), director of the Johanneum in Lüneburg, stated on the occasion of the end of the Seven Years' War: "War, no matter which side you look at it from, is always a destroyer of people. Not only directly, but also indirectly." This may be a generally applicable warning, not least in view of the current situation in Ukraine, but it comes from the invitation to a peace celebration to mark the end of the Seven Years' War. Stockhausen's further remarks in his peace speech on the indirect consequences of war were particularly relevant to the topic of medicine, illness and war. Among other things, he reported on the high casualties caused by infectious diseases and epidemics, which were mainly caused by the military hospitals. In Lüneburg in particular, typhus and other infectious diseases had raged in 1758, costing the lives of numerous people and leaving the town traumatised.

Stockhausen's remarks show the extent to which contemporaries perceived the danger of a war-related outbreak of infectious diseases as an existential threat. This example illustrates central features of the perception of and handling of infectious diseases in war during the early modern period: people in the early modern period saw a self-evident connection between the occurrence of infectious diseases and war. They therefore regarded war as a direct threat to public health. There was an infrastructure for medical care, for example military hospitals, and the municipal authorities in particular endeavoured to prevent the spread of infectious diseases through hygiene measures. It was therefore possible to counter the threat of infectious diseases during the war both therapeutically and preventively.

However, it is important to consider these measures in the context of contemporary medicine and the way society dealt with infectious diseases. The war presented early modern societies with particular challenges, but also contributed to changing long-term ideas about the spread and course of infectious diseases. The focus in the following is therefore on two questions: Firstly, what specific ideas of morbidity and mortality in war emerged under the impression of increasingly quantified military medicine? - And secondly, what possibilities were there, especially in the urban context, for various actors such as the military, the sovereign and local authorities and the population to deal with the danger of infectious diseases in times of war?

Other aspects are certainly left out. The experience of illness and injury by soldiers directly affected by it, for example, is only dealt with in passing. First, however, a brief overview of the fundamentals of military medicine and the global dimension of illness and war at the time of the Seven Years' War will be given. I will then look at the medical view of morbidity and mortality before focussing on the specific handling of the risk of epidemics during the Seven Years' War.

Structures and institutions

Since the 1990s, the connection between the military, medicine, illness and war has received greater attention in historical research. The Anglo-Saxon social and cultural history of medicine in particular has produced works, primarily on the British and French military, which allow a comparative perspective to be adopted. The following findings on the genesis and institutionalisation of military medicine in the early modern period can be briefly summarised. The first indications of regulated care for sick and wounded soldiers can be found in the late Middle Ages in the form of medical funds. These were used to finance the care of sick and wounded soldiers by surgeons and also in municipal hospitals.

Secondly, there is evidence of permanent medical facilities in Flanders since the late 16th century. Since then, European armies have had their own field hospitals. Thirdly, military medicine became an integral part of permanent military infrastructures in the second half of the 17th century. Examples of this are the large invalid hospitals that were first established in Paris and Greenwich.

Fourthly, there was a close interdependence between civilian and military healthcare. Physicians and surgeons in the service of the sovereign were responsible for the organisation of medical care during the war. For many surgeons, service in field hospitals and as field surgeons was an integral part of their career path before they could settle down. Fifthly, the question of how to deal with sick and wounded soldiers became increasingly the subject of public political debate in the course of the 18th century, particularly in Great Britain. The sick or wounded soldier's body also became a statistical variable that was factored into loss calculations.

The period of the Seven Years' War represented a turning point in this context. In medicine, clearer and evidence-based ideas about the connection between illness and war were formulated, while the military, especially its administration, developed ever more sophisticated administrative tools and collected data on the military population. However, this initially had little direct impact on the facilities for the care of sick and wounded soldiers.

In most armies of the early modern period, soldiers were provided with medical care by company surgeons and regimental surgeons as well as town and garrison doctors from the second half of the 17th century onwards. The sick and wounded were usually treated in their quarters and soldiers who were not on site were reimbursed for their treatment costs from their regiment's medical fund. Similar arrangements existed on the ships of the navy, whose fleets were sometimes accompanied by their own hospital ships.

On campaigns, this system was routinely expanded to include temporary field hospitals. The staff for these hospitals were recruited from personal and court physicians and surgeons, the official physicians and surgeons as well as the field surgeons and enlisted journeyman surgeons. In addition to soldiers' wives and widows, locally recruited day labourers and sometimes invalid soldiers also served as nursing staff. The hospitals could be set up as main hospitals at fixed locations - often together with magazines and the field bakery - or follow the army as flying hospitals. As a rule, there were no special military hospital buildings. Castles and churches were used just as much as private houses or barns. Seen in this light, military hospitals did not manifest themselves in specific architecture, but primarily in the administrative practices handed down in the records.

Global challenges

If the Seven Years' War is viewed as a conflict with global dimensions in military and political terms, this also applies to war-related illnesses, morbidity and mortality. Here are just a few brief remarks. On the European theatre of war, physicians and surgeons regarded the well-known war diseases, especially various types of fever such as typhus or intermittent fever - i.e. malaria - as a major threat to the health of the armies. In addition, dysentery was feared as a particular challenge for military medicine with its high risk of infection and special demands on hygiene in camps and military hospitals.

In the overseas theatres of war, the diseases known from Europe were joined by foreign pathogens such as yellow fever, against which the European soldiers had hardly any defences, which sometimes resulted in great losses. This was one of the reasons why the Royal Navy began to systematically expand its hospital infrastructure in the Caribbean after the War of the Austrian Succession. Initially on Jamaica, and later on Antigua and other Caribbean islands under British control, hospitals modelled on those in Greenwich and Portsmouth were established.

These functional buildings were used for the permanent care of sick and wounded British sailors and helped to significantly reduce the losses of the British navy in the second half of the 18th century. In North America, on the other hand, the regular British and French troops often suffered from shortages during the Seven Years' War. For example, although 58 British soldiers lost their lives in the Battle of Quebec in September 1759, almost ten times as many died the following winter, many from scurvy.

Conversely, the war in the colonies also had a massive impact on the health of indigenous populations in particular. Smallpox introduced from Europe had a major impact on morbidity, mortality and morale during the war in North America. While the majority of soldiers from England probably had a high degree of immunity to smallpox, the North American recruits were significantly less protected against infection. The fear of an epidemic was correspondingly great among them. However, the indigenous population was much more severely affected. Largely without immune protection, they were at the mercy of the disease. However, the assumption that the British military systematically used smallpox as a biological weapon during the Seven Years' War is controversial. In any case, the spread of smallpox in the second half of the 18th century in the course of colonial expansion in North America had catastrophic consequences for the indigenous population. The Europeans systematically exploited the disintegration of indigenous culture and political-military capabilities promoted by the spread of smallpox to further their colonial interests.

Morbidity and mortality in the Seven Years' War

While the suffering caused by illness and war can hardly be quantified or expressed in figures, soldiers and their physical condition became the direct object of administrative practices in the early modern period. In order to manage this human capital, tools from bookkeeping and regimental and military hospital economics were used. Lists, tables and accounts were originally drawn up to record the number of soldiers and calculate the costs of their pay, food, transport and replacement.

It would now be reasonable to expect that the data collected would provide reasonably reliable information about the losses of the armies. However, this is by no means the case. For one thing, the records are incomplete, meaning that complete series of figures on casualties and sick leave over a longer period of time are rare. In addition, the surviving data is not accurate, i.e. there are gaps and the data is incorrect. However, there are also exceptions. From the War of the Austrian Succession, for example, compilations of monthly lists have been preserved which provide information on the status and losses of the Hanoverian regiments in the Netherlands. In these lists, the actual status, sick leave and casualties were stated and recorded by regiment. However, this is also aggregated data, the basis of which is unclear. The data is also incorrect: for example, if you add up the losses due to sickness, deaths, deserters and departures, the total minus the new recruits does not correspond to the number of missing personnel. It is also not clear exactly what the categories refer to. Although it is obvious that "those who died" refers to those in the military hospitals, it remains unclear exactly what is meant by "those who left".

Nevertheless, some more general observations can be made on the basis of the data. For example, morbidity from July 1744 to April 1748 averaged 6.3 %, but was significantly higher in the war year 1745 at 9.7 %, in which the Hanoverian regiments were increasingly involved in hostilities and suffered heavy losses, including at the Battle of Fontenoy in May 1745. What can also be seen from the available data are trends in morbidity and mortality and, above all, the effects of individual war events.

What is remarkable about the figures just presented is that they are hardly comparable with the figures known for the Seven Years' War. The following figures are taken from Boris Urlanis' still widely cited work on the balance of wars (Berlin, 1965) in Europe since the 17th century. In it, he analysed the older demographic and above all military historical research on human losses in a meta-study in the 1960s. For the Seven Years' War, he gave the total losses of the armies in the European theatre of war as 550,000 soldiers and officers.

For the Austrian army, he broke down the figures further and gave the distribution of casualties as 26 %, a further 15 % died of wounds and the majority of 59 % died of disease. However, these figures contradict other figures given by Urlanis when he elsewhere stated the mortality rate from disease in the Austrian and Prussian armies at 80 %. What is probably undisputed, however - and this was true at least until the American Civil War - is that far fewer soldiers were killed in battle or died from their wounds than from disease in the wars of the early modern period.

The medical view

This was particularly evident in the field hospitals. Data about the patients was also collected there in a variety of ways. However, this information is even sparser and more fragmentary than that of the war registries. For the Prussian army, however, data have been handed down according to which the mortality rate in the Silesian military hospitals during the Seven Years' War was 19.4 %. In the field hospitals, data collection could be based on traditional medical recording practices, such as patient journals and case histories, which were included in publications such as the collections of case histories by leading Prussian field physicians and surgeons after the Seven Years' War or published in medical journals.

Another form of data collection is the medical journals that were kept in the infirmaries of the field hospitals. They were used to continuously document the diagnoses, treatments and progression of illnesses carried out by different personnel. Such journals were introduced at the Berlin Charité, which was also a training hospital for Prussian field surgeons, in the early 18th century.

As early as the War of the Austrian Succession, such data and that of the military administration was used by physicians to make fundamental observations on the connection between illness and war. In his highly influential Observations on the Diseases of an Army (German edition of 1754) from the War of the Austrian Succession, the British field surgeon John Pringle claimed to be able to calculate "[...] how many men could be relied upon to serve at different times of the year" on the basis of empirical observations. Pringle attributed the soldiers' general state of health to external environmental influences and the sex res non naturales, i.e. light and air, food, exercise and rest, sleep and wakefulness, excretions and what he called the "excitations of the mind".

Pringle's aetiology was thus deeply rooted in the humoral pathological ideas of European medicine, which was rooted in ancient traditions. In this context, Pringle not only provided information on the relative sickness rate of an army on the basis of monthly reports, but also placed it in a statistical relationship to specific environmental factors - in this case seasonal climatic conditions - and provided information on the typical conjunctures of morbidity during a particular campaign.

For Prussia, it can also be shown how practices that were originally economically motivated changed the way doctors viewed morbidity in the army. In Prussia, for example, reports from the field hospitals were routinely submitted during the Seven Years' War. In tabular form, these reports provided an overview of the number of patients, broken down into officers and privates, at the beginning and end of the reporting period and, in between, the number of convalescents, invalids and deceased. Such reports were usually accompanied by reports in which the General Field Medical Officer or the Hospital Director provided information about unusual incidents in the military hospital, discussed personnel issues and commented on the development of morbidity and mortality.

In a letter accompanying a report from Torgau in November 1760, for example, the Prussian Field Surgeon General Christian Andreas Cothenius (1708-1789) not only reported on the increased convalescent rate due to the improved conditions in the hospital. Based on his observations, he also predicted that he would be able to send a further 2,500 wounded back to the army as convalescents in the coming month and a further 1,500 within the following three months. He also stated that he would be able to discharge 650 sick convalescents in the next two months.

Cothenius did not establish a correlation between the patients' state of health and their treatment with morbidity and mortality rates. However, he did use the data and his observations in the field hospital to make predictions about the number of convalescents to be expected in the future.

Pringle and Cothenius took a quantifying view of the body and shifted the focus away from the individual body towards larger groups of patients. A significant shift can be seen here when, in the mid-18th century, medicine appropriated quantifying practices from the body economy of the military and military administration. And this shift confirms the findings that date the "birth of statistics" to the 18th century.

Around the middle of the 18th century, the doctors and surgeons in the field hospitals developed a view of the hospital population that turned it into a statistical and therefore dynamic variable, whose changes potentially allowed conclusions to be drawn about the physical condition of the army as well as the possibility of influencing it through the targeted application of treatment methods and preventative measures. However, the following example of dealing with the danger of the spread of infectious diseases during the Seven Years' War in north-west Germany clearly shows that such a view was by no means guiding action in the sense of evidence-based medicine in the mid-18th century.

The "war epidemics" and the state healthcare system

Given the course of the war in 1757/58, it is not surprising that north-west Germany was particularly affected by war-related epidemics in 1758. From the late summer of 1757 until the autumn of 1758, large-scale troop movements took place in the Electorate of Hanover. In the course of these movements, sources report outbreaks of so-called "spotted fevers" and "hot fevers". The worst affected areas were along the Weser, the most important supply line, and in the Lüneburg Heath, including the towns of Lüneburg, Uelzen and Celle, which were affected by multiple passages and quartering. This was clearly reflected in the natural surplus population, which was much more negative in Lüneburg, Uelzen and Celle in the epidemic year of 1758 than in other crisis years.

However, it must be added here that the effects of the war are selective and are more likely to be explained by the specific local conditions. For example, the natural surplus in Wendland in 1758 was no different from other crisis years in the late 1760s and 1770s caused by crop failures and economic crises. This showed the general vulnerability of pre-industrial populations at the natural ceiling.

In any case, the acute epidemiological effects of the war were clear to contemporaries. In March 1758, the Nützliche Nachrichten, published in Hanover, had already asked its readers, under the impression of the effects of the war on the Electorate of Hanover, how the combination of disease and war could be explained and what countermeasures could be taken. In an answer dated 28 April 1758, an anonymous author, presumably a doctor, explained the causes of the concurrence of disease and war and what the most suitable measures would be to prevent or at least contain the outbreak of these "war diseases".

With regard to possible preventive measures to prevent the spread of infectious diseases, he suggested paying particular attention to cleanliness on the streets, in the quarters and military hospitals, strictly separating the sick and wounded in the military hospitals, regularly airing and fumigating the infirmaries and paying attention to the personal hygiene and healthy diet of the soldiers.

When Daniel Philipp Rosenbach (1691-1760), town physician of Hannoversch Münden, approached the war chancellery in Hanover with his draft for hospital regulations in 1759, he proposed similar measures. He also divided the patients into three classes: those suffering from infectious diseases, those afflicted by so-called "common fevers" and the wounded. As he feared infection through "[...] the evaporation of evil air and poisonous miasmata [...]", he recommended that patients be housed separately in detached buildings on the outskirts of the city so that "[...] the vapores gravolentes and the foetores of the neighbours from the latter might not bring harm and disgust, nor morbos epidemicos."

This view of the connection between war and epidemics was widely shared beyond medical circles and was rooted in the Hippocratic-influenced Western medical tradition. Humoral pathology and miasma theory made preventive measures based on personal and public hygiene, dietetics and, in case of doubt, quarantine measures plausible. The state healthcare system operated within a similar framework.

The epidemiological dimension of the war posed a problem for both the sovereign and the local authorities. As early as 6 October 1757, the government in Hanover issued a decree for the cleaning of houses, alleyways and hospitals, which was renewed on 30 March 1758, immediately after the French army had left the electorate. The local authorities had a certain amount of leeway when it came to implementation, and in Nienburg, for example, the council introduced regular rubbish collection in April 1758 and instructed the town syndic to ensure that streets and houses were regularly fumigated. He was also to ensure hygiene in the neighbourhoods, especially where sick people were housed. Burials in mass graves were forbidden, as these "[...] gave off an abominable stench and could infect the air."

Military hospitals in urban areas

Particular attention was paid to the military hospitals with regard to public health. They were the most important facilities for the care of the sick and wounded during the war. During the Seven Years' War, main hospitals were set up at central care centres. In north-west Germany, these included Münster, Osnabrück and Nienburg. Flying military hospitals followed the army in the field. In conclusion, I would like to briefly illustrate the effects of the presence of such military hospitals on the ground and the consequences they had for the perception and handling of the danger of the spread of infectious diseases using the example of Hamelin in the years 1757 to 1759.

Alongside Nienburg, Harburg and Göttingen, Hameln was one of the most important electoral Hanoverian fortresses. A garrison had been stationed there since the late 17th century and barracks buildings were erected to house it. During the Seven Years' War, the public buildings on the market square (Nikolaikirche, town hall, Neues Gebäude, Kommandantenhaus), the Gasthaus zur Sonne and the barracks near the cathedral in the south-west and at the Zehnthof in the north-west of the town were occupied by military hospitals.

The first French military hospital was set up at the end of July 1757 after the Battle of Hastenbeck. As the pastor of the cathedral church, Johann Daniel Gottlieb Herr, reported, the conditions there were terrible: "The dying in there was extraordinary and only the very fewest recovered, especially those lying in the market church, which is why they were finally taken out and placed in the Rahthaus." According to Hamelin's older town history, over 4,000 patients died there by the end of 1757 and were buried in mass graves in the cathedral churchyard and in front of the Mühltor gate.

The size of the Hanoverian military hospital, which partly existed at the same time, varied over time and grew considerably during the year 1758. It was run by the town doctor of Hamelin, Johannes Noréen, and a town surgeon, Ludwig Christian Lammersdorf, who was brought in from Hanover.

The hospitals were a constant source of concern for the town, and so at the end of October 1758 the Hamelin town council once again complained to the government in Hanover: "We are therefore afraid of infectious diseases, and have therefore requested that the sick be brought to the barracks, where the free air can promote their recovery and the water flowing past can carry away the impurities that might cause a contagion. We are not talking about the blessed here; there is enough room for them in the city [...]."

However, the reason for the request to transfer the patients suffering from infectious diseases was not the immediate danger of an outbreak of an epidemic, but a long-simmering dispute with the garrison commander, Lieutenant General Georg Friedrich Freudemann. While the military wanted to keep the military hospitals in the central buildings around the market square, the town endeavoured to move the patients to the barracks at the Zehnthof on the outskirts of the town.

In this dispute over the accommodation of the military hospital, the council surmised that the military's motives were that the officers housed in the barracks did not want to do without the comfortable quarters and the free firewood provided to them there. The city pointed out that the accommodation for the military hospital should not be provided as part of the billeting at the expense of the city, but would have to be organised by the commissariat at the expense of the war chest. At the same time, the city showed itself willing to compromise by agreeing to take slightly wounded soldiers into the regular quarters.

The situation had actually long been clear. On 18 October 1758, the War Chancellery in Hanover had already decided in the town's favour to separate sick and wounded soldiers and transfer the sick to the barracks. Following another complaint from the Hamelin council, the war chancery was forced to intervene and instructed the garrison commander to at least separate the sick and wounded soldiers and move the former to the barracks on the outskirts of the town in order to prevent the further spread of infectious diseases.

This example clearly shows how strongly the arguments of the Hameln Council and the War Chancellery relied on contemporary epidemiological and military medical commonplaces. However, the fear of an epidemic outbreak was only one motive for the relocation of the military hospital and at the same time a rhetorical device. Other motives were superimposed on the medical-epidemiological discourse: the conflict of status between the military and the city authorities over privileges in quartering, as well as conflicts over resources between the war chancery, the city and the military.

Conclusion

Finally, if we look at the early modern interpretation of "epidemics of war", it initially resembled the interpretation of other epidemics and natural disasters. To contemporaries, they appeared to be a punishment from God following the Second Book of Moses (Exodus) or were associated with the horsemen of the Apocalypse (war, famine and death) in the context of eschatological interpretations. However, such narratives generally only had a topical function at the time of the Seven Years' War. In other words, the assumption that illness and war went hand in hand as a matter of course was no longer interpreted metaphysically or scrutinised in any other way. Instead, this connection was rationalised within the framework of contemporary medicine. Its assumptions were essentially based on concepts with ancient roots, such as humoral pathology, miasma theory and contagion as the cause of disease, as well as sex res non naturales as the therapeutic basis. It was not until the middle of the 18th century that approaches to a medical-statistical view of war-related epidemics could be observed, although these did not compete with traditional interpretations and were not yet used as a basis for evidence-based epidemic control. In fact, the first attempts to do so were not made until the 19th century.

Whether the war epidemics came with the passing soldiers or were endemic was secondary in the early modern period. More important were the specific conditions that favoured the spread of contagious diseases and the practical knowledge required to prevent and contain epidemics. When dealing with infectious diseases during the Seven Years' War, practical questions took centre stage: What measures could be taken to prevent or contain epidemics? Who was responsible for this? How could epidemic protection, military and economic interests be reconciled?

Accordingly, public health measures were the main starting point for the municipal and sovereign authorities. At the same time, they sometimes led to conflicts when, on the one hand, the military saw its options and privileges restricted. On the other hand, the subjects sometimes saw their own health threatened if the authorities did not appear to be sufficiently fulfilling their duty to prevent the spread of epidemics in times of war.

Some of the previous observations drew attention to ideas that are foreign to us today. Others, however, are also familiar to us in the current pandemic: traditional measures to contain the epidemic such as isolation, quarantine and hygiene measures, statistical models with limited significance, infrastructure that has reached its limits in the face of the catastrophe, or the subjugation of interpretations of the epidemic to particular, political and economic interests. One thing, however - and this should not go unmentioned - was largely foreign to the 18th century: namely, to seek the cause of the outbreak of war epidemics in the dark machinations of a conspiracy of any kind.