Since the Peace of Westphalia, the major multilateral conflicts have been negotiated and ended at peace congresses. In the Seven Years' War, too, it seemed that a major congress would be held in 1761, alongside the peace talks and attempts at mediation that accompany all wars. There was already talk of the imperial city of Augsburg, with its image of peace, as the venue for negotiations, and the first envoys, advisors and observers were preparing or, like the well-informed papal diplomats, were already on their way to Augsburg. But the congress plan fell through and did not materialise even after later attempts. All sorts of individual causes can be cited for this, such as the Bourbon family pact between France and Spain, which shifted the balance of power once again at an inopportune time, but the fundamental problem should not be overlooked. The global dimension of this war, with its multitude of worldwide players, different competences and interests, would have simply overstretched the tried and tested European conflict resolution model of the Congress.

The Seven Years' War thus became the first major conflict in over a century that was no longer ended by a peace congress, but by a series of individual peace agreements staggered over time. First, as is often overlooked, in Eastern Europe the Peace of St. Petersburg on 5 May 1762 for the departing Russia. Then, with the Preliminary Peace of Fontainebleau in November 1762, the Peace of Paris concluded on 10 February 1763 between the competing powers overseas and in Europe, France and England. Finally, there was the purely internal peace of Hubertusburg on 15 February 1763. The impracticability of a global peace congress even at that time suggests that the European and non-European pacification strategies should first be treated separately. Unlike overseas, all peace settlements in Europe were characterised by the principle of restitution of the status quo ante bellum. And not just as a general guideline, which was then followed by exceptions and modifications negotiated in the treaty, but a territorially and politically actual restoration of the respective pre-war status quo.

No fewer than seven treaties representing different parts of the world: on the one hand, the hybrid peace of Paris, which included both perspectives, and on the other, the continental treaties of St. Petersburg and Hubertusburg and others, each with Prussia as the main combatant. Can there even be a winner at such a confusing end to the war?

Even if one may doubt whether there can be winners in wars at all, especially not with human losses and destruction in seven years, which have been compared to the catastrophes of the world wars of the 20th century in relation to the level of development at the time, the question should be asked here as to which of the actors won in the political sense. The reason for this is that supposedly self-evident facts are in circulation, the correction of which is being debated in research and which are becoming astonishingly relevant today. I will start with the most spectacular case.

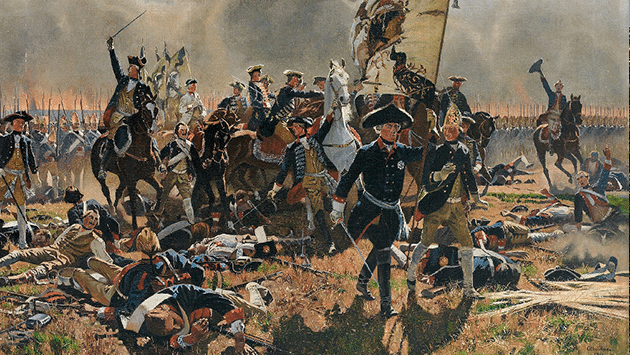

Why the great warrior Friederich lost the Seven Years' War

According to popular opinion, it was the Prussian King Frederick who won the Seven Years' War. Could the capitalised general, who, with the help of Prussian propaganda and national historiography, skilfully passed a series of battles that emphasised victory, have lost the war? Had he not held his own against the three continental powers Austria, France and Russia, albeit as the most heavily equipped military power? And did he not maintain the conquered Silesia and the pre-war state demanded at the end of the war with a monomaniacal policy of perseverance and "miraculous" vicissitudes?

Indeed, on the 300th anniversary of his birth, popular handouts still spoke of Frederick's "victory" in the Seven Years' War. This even applies to critical contributions, which also counter the enormous loss of life and destruction as the cost of the supposed "victory". Even the warlord himself admitted in strong terms the desolate post-war state of his country, but he never spoke of a victory. In the end, the king even avoided the ceremonial entry into his residence in front of the cheering Berliners. As the historian of his own war, he even believed he had to justify a peace treaty, not because he had not been willing to compromise earlier to limit the damage, but because he had not fought on to get more out of it. Frederick knew that he had lost the war. But only one person could know for sure why: the king himself. After all, in the secret part of his state document 'Political Testament', he had planned further conquests immediately after Silesia, including West Prussia and, with priority, Saxony or at least part of it. If the invasion was carried out preventively from a defensive position, into which he then actually got himself with deception and manipulation of documents, and the secret of the true war aim was kept, the damage would be limited if he did not achieve everything or even failed. And so it came to pass. However, the text was not discovered until over a hundred years later, and some still do not believe it today, although Frederick later gave these war aims to his successors, who actually realised them in later times. For this time, however, the risk-taker could be glad that the belated Prussian state formation, which he jeopardised once again with his frivolous annexation goals in this war, narrowly survived in the end.

And the other players in the Seven Years' War? Perhaps we should generalise the question of war aims and measure the success of the war by the degree to which they were achieved. Did the other main combatants in Europe achieve any of their war aims? As is well known, Maria Theresa and the Viennese court did not. All of Silesia remained lost forever, although it had already been partially reconquered and the fortress of Glatz remained occupied by Austria until the very end. A further rise of Brandenburg-Prussia was halted, but the intended reduction of its position and power in the empire and in Europe failed. France and England agreed in the preliminary peace treaty of Fontainebleau in Paris to no longer support their respective allies militarily or financially, thus drying up the war in Europe. France's expectation of receiving compensation in the north-west in the event of an Austrian recovery of Silesia had to be abandoned and the already effectively occupied Rhine-Prussian territories had to be released again. England, the "appendage of a lousy electorate", as William Pitt the Elder sarcastically put it, retained the Crown's personal union with Electoral Hanover unchanged, although this lost significance with the change of throne to George III.

And the often forgotten Petersburg Peace of 5 May 1762, which set in motion the status quo ante bellum series with its miracles? The war aim of the Russian government under Tsarina Elisabeth, which was pushing for war, had indeed been to eliminate the obstructive Prussian competition on its way westwards. This had been achieved spectacularly with the occupation and possession of the Prussian heartland around Königsberg, which had already sworn an oath of allegiance to Tsarina Elisabeth. The first "miracle of the House of Brandenburg", as Frederick himself wrote to his brother, was that the victorious Russians did not also take possession of the capital Berlin after the Battle of Kunersdorf. The second "miracle" was that after the death of the war czarina Elisabeth, her successor Peter I made peace with Frederick and gave back all Prussian territorial gains, even adding a Russian-Prussian mutual assistance pact. His wife, Catherine the Great, who subsequently came to power in a palace revolution, cancelled the alliance with Prussia, but left Peter's peace treaty in place. The Roman Curia took the opportunity to congratulate Maria Theresa on averting the danger posed by the Frederophile Peter, this time as one of the miracles for the House of Austria. This meant that the pre-war situation could be restored without any conquests or territorial changes in Europe.

So none of the opponents won the war in Europe. Measured against the far-reaching war aims and the amount of force used, the peace compromise was a meagre result. The Prussian court was already asking itself why Europe had gone to war at all in order to restore the pre-war situation on all sides. It was a good question, and one that should still be asked today in similar cases. Peace in Europe could be regained with this rarely so consistently applied means of conflict resolution, which was to set everything back to zero, as it were. That was no small feat. But it also meant that all the players had failed in their war aims and lost the costly war in Europe. All except one, for whom the restoration of the pre-war state was the war aim itself.

The triumph of the federal empire

In fact, only the federal Reich of the German Nation achieved its war aim by regaining the pre-war state. The Reichstag, the imperial districts and the imperial army did not go to war to reclaim Silesia, which was in any case only loosely bound to the empire and had long since been ceded to Prussia under international law, for the revisionist court in Vienna, but to liberate Electorate Saxony, which had just been invaded, to put the notorious Prussian warmongers in their place this time and to restore constitutional order. And they succeeded. No one will claim that the Imperial Army won major battles or even the war militarily. But it did make an effective contribution to the liberation and defence of Saxony under its own command in cooperation with the army of the Viennese court and its allies. Furthermore, it was a visible sign that the federal empire was on the side of the imperial court, but was a force in its own right. At the Diet of Regensburg, an independent imperial policy was pursued throughout the war, which countered Prussian attacks, but also corrected Viennese exaggerations and, for example, preferred to stop the ostracisation of Frederick, as had been the case with the Electoral Palatinate in the Thirty Years' War and Electoral Bavaria in the War of the Spanish Succession, which led to pacification problems that were difficult to solve, and to move towards peace. In addition to the great powers, individual imperial estates such as Bavaria and the ecclesiastical electors, even the small court of Bayreuth, the Duke of Saxe-Gotha or the Count of Neuwied, came forward with mediating peace proposals or provided their services in corresponding exploratory talks. Imperial mediation was also discussed. No imperial representative sat at the table in Hubertusburg, but this is a mock proof of the allegedly increasing forgetfulness of the empire. The Reichstag had already given the imperial court a comprehensive mandate to negotiate on the occasion of the planned peace congress in Augsburg, the imperial estates secured the end of the war through agreed truces and neutrality, and the imperial war also became an imperial peace through the inclusion of the empire in Hubertusburg and the declaration of the imperial head before the Reichstag, which, with the territorial integrity of Saxony, guaranteed what the empire had taken up arms for.

Indeed, the Electorate of Saxony, traditionally close to the empire, played a major role in the realisation of the Hubertusburg Peace. While August III had disappeared to his neutral second country as King of Poland together with his chief advisor Heinrich von Brühl, the "young court" of the heir to the throne Christian, who was closer to the empire, returned to Dresden and now brought the Leipzig publisher's son and later Saxon statesman and baron Thomas von Fritsch into position. He had long established good contacts with Frederick in order to keep the excessive plundering of Saxony, with which he financed his war, within feasible limits. As both the Viennese and Prussian courts were exhausted and stuck in a stalemate and neither wanted to admit this by making a peace offer, Fritsch took it upon himself to resolve the situation. He wrote a letter to Kaunitz, agreeing with him to make peace for the sake of Saxony and its suffering. Kaunitz replied that it should not be up to Maria Theresa and him, and with this correspondence he travelled to Meissen, which was once again occupied by Frederick, to ask for more protection for Saxony and to draw out the east-sensitive correspondence. Frederick turned away brusquely when he saw the German inscriptions - as reported in the old, but source-based and only monograph on the Peace of Hubertusburg - and forbade himself to read them aloud. But Fritsch knew his counterpart and drew out a summary in French, which met with the interest of this most absurd of all German national heroes and led to the initiation of negotiations.

The Peace of Hubertusburg on 15 February 1763, which finally concluded the Seven Years' War, was negotiated in just six weeks and signed immediately after the definitive Peace of Paris. The eponymous hunting lodge, badly damaged by Prussian plundering, was a somewhat improvised negotiating venue, but it was located halfway between the Saxon royal seat of Dresden, which was actually planned, and Frederick's headquarters, now in Leipzig, and the envoy of the imperial court was "not to run after the king" (Kaunitz), despite all the Saxon insistence on an urgent peace. Collenbach acted for the Viennese court in close liaison with the State Chancellery, while Brandenburg-Prussia was represented by the state publicist, future minister and peace expert Herzberg and Fritsch continued to act as a mediating host on the spot for Saxony, which was the main party concerned, and at the same time negotiated its own peace treaty with Prussia for Saxony. In terms of content, the peace treaty with Saxony contained not only favourable final financial arrangements for Saxony, but above all the modalities of the withdrawal and release of Saxony by the Prussian troops. Considering that all this took months and years after the Peace of Westphalia, the detailed regulations and compliance with the speedy withdrawal of the Prussian troops is astonishing. Saxony lost the Polish crown, but this had nothing to do with Hubertusburg, but was due to the coincidence of the death of the last Saxon elector-king soon after his return to his Saxon residence. Under Fritsch, the reconstruction of Saxony as an economically and socially powerful German state was all the more determined and successful, a "re-establishment" that was in no way inferior to the much-cited Prussian one, rather the opposite.

However, it is only possible to properly assess the success of the empire if one realises the dangers that threatened and the attacks against the imperial constitution that were fended off. The most astonishing thing is the attempted evocation of a religious war through the unholy co-operation of papal diplomacy on the Catholic side and the English and Prussian press on the Protestant side. But the imperial head and experienced imperial management carried out his official duties and silenced Rome, and almost all Protestant imperial estates placed imperial law above confessional solidarity. No, the empire did not allow itself to be talked into a religious war, neither by Rome nor by Potsdam.

Secondly, Prussian plans to secularise prince-bishoprics were another attack. It was part of Prussia's tradition to rustle around with such plans, but things got serious during the Seven Years' War, as Frederick in particular was now looking for compensation territories for a peace with land gains. According to this plan, allied Hanover was to receive the lion's share as compensation for the Prussian acquisition of Saxony. Vacancies in ecclesiastical electorates - such as five bishoprics upon the death of Elector Clemens August of Cologne - or in the endangered Franconian imperial district of Würzburg and Bamberg were quickly filled. If a single prince-bishopric had been broken out of the imperial church and used for peace compensation, this could have triggered a chain reaction and undermined the legal protection of minor imperial estates.

Thirdly, an even more drastic attack on the imperial system was Frederick's secessionist Sonderbund policy in favour of an enlarged Prussia and a larger Hanover. Gustav Berthold Volz has already reconstructed it from the sources under a remarkably clear heading: "Frederick the Great's plan to tear Prussia away from Germany". But the defenceless Empire of the German Nation also survived this attempt at assassination by the supposed national hero, which perished in the military failures of the Prussian secessionists.

However, the greatest triumph of the empire, which is still not fully understood today, was that Frederick the Great, having been unable to destroy the imperial system through annexation, secession or confessional division and having experienced its power, returned to the empire himself with his barely saved state. The Prussian Reichstag envoy Plotho, who ranted at the Perpetual Diet in Regensburg and distributed Prussian party pamphlets, but remained present there in the midst of the war and thus maintained the imperial nexus of Brandenburg-Prussia, formed a bridge for this. Finally, the same Frederick, who had pursued a purely obstructive imperial policy before the war and had blocked a Habsburg succession in the empire for years, now promised in a secret article on the Peace of Hubertusburg to give his vote for the succession of Joseph II, which was actually realised in 1765 - a lasting success for the emperor and the empire! As the "anti-Caesar", Frederick was able to continue to play the role of counter-emperor, but not outside the imperial system, but within it. The concept of emerging German dualism fits better here than the fantasies of victory and assertions of great power, even though there were actually still more than two politically relevant states in Germany. However, it is a misconception that a two-emperor constellation was a defeat for the empire or even the beginning of the end. On the contrary, Frederick had learnt something new and had now arrived in the empire; indeed, in the words of Volker Press, the late-comer became the "most successful imperial politician". Between the outposts in Vienna and Berlin, the always astonishingly flexible empire gained further room for manoeuvre by being able to call upon the other as an advocate in the event of encroachments by the one. The Frederician rhetoric of victory is not the appropriate way to deal with the Seven Years' War, then as now, but Frederick's belated learning process in recognising the federal German system could be a model worthy of further investigation.

State-building as a transatlantic parallel

From a non-European perspective, the settlements, which were essentially negotiated between the adversaries France and England at the Pre-Peace of Fontainebleau and concluded in Paris without the participation of the indigenous peoples and allies, seem to have resulted in England being the clear winner worldwide with huge territorial shifts in the claimed and contested territories on several continents, islands and sea trading bases. What is astonishing, however, is that the public on both sides was dissatisfied with the result. In France, of course, about the painful losses overseas, but also in England that the negotiations had not yielded more. If there was criticism of the peace treaty from both sides, then perhaps it was not a bad one. Lord Bute did not want to provoke a war of revenge by exercising moderation, and Minister Choiseul referred to the preservation of France's position on the continent with the malicious bon mot that France had lost the stables but the castle was standing. With a few French exceptions, the lost "stables" were the trading posts on most of the Indian subcontinent, which went to England along with a large number of other bases across islands and continents, but above all the repression of France in the hotly contested North America. This particularly affected Canada in the north, the areas around the Great Lakes and the Mississippi, especially in the south. Despite the involvement of Spain with complicated and unsustainable exchange relations over Louisiana and Florida, it was clear that instead of a French north-south bridge, the door had been opened for an English-dominated east-west expansion.

But this no longer benefited Great Britain. For although this undoubtedly set the course for the dominance of the English language, culture and colonisation in North America, it was more of a Pyrrhic victory for British political rule there. The "French and Indian War" was also the cause and precursor of the American settler policy against British rule. Not only did the American-British conflict over the assumption and parliamentary legitimisation of war debts through taxes break out, but differences in power politics between British administrative-military rule and the colonists' self-government and militia had already come to light since the outbreak of the Seven Years' War in the Ohio Valley in the joint struggle against France.

During the war, the political self-confidence of the colonies was strengthened and gradually developed into a state of their own. It is no coincidence that later founding fathers of the USA, such as George Washington as an officer and Benjamin Franklin as a politician, were already involved here. The war-induced federal policy of the colonies, initiated and advised by Franklin, whose Albany Plan of Union had already considered the position and cooperation of the colonial parliaments and an overall power with responsibility for war and peace, became an institutional forerunner of the organisational issues to be resolved in a future state structure.

Despite all the differences that initially suggested a separate measurement of European and non-European pacification strategies, there is also a transatlantic parallel in the embedding in the state-building process emanating from Europe. Not only did the expanded trading empire of the East India Company and the treatment of indigenous rulers in India become increasingly nationalised in the sense of Great Britain, but there is an even more far-reaching parallel. Just as the federal German Empire, which was once again renewing itself in terms of practical and institutional state theory, into which the former peace disturber on duty with its belated state formation since Hubertusburg, which was still in need of leaning, finally integrated itself and helped to shape it, the lasting significance of the Peace of Paris was that it became the starting point for the federal solution that was already emerging for North America.

The latest research findings of a working group led by the experts Volker Depkat, Jürgen Overhoff and the author show that the founders of the state were inspired not least by the theory and practice of the imperial constitution, especially with a push for adaptation and reform after the Seven Years' War, as indicated here. Thus it is precisely the two victors who, although they did not formally receive their own peace treaty, must be included or anticipated: in Europe the federal Empire of the German Nation and in America the United States of America. From the global perspective of the Seven Years' War, the joint significance of Paris and Hubertusburg is their contribution to the process of state-building, and if this transatlantic bridge is sustained, as a thematic volume in progress will show, especially the federal state-building that continues to have an impact to the present day.

Epilogue

This article is a historical one, but it has been overtaken by current events. This country "must not lose the war" was a common refrain after a highly armed military power invaded its neighbouring state on 24 February 2022 under the responsibility of a single man with false claims and hidden annexation objectives. Although agreed, titled and left as it is from a different perspective, the above text can also contribute something worth considering to historical peace research. After working through the causes of the war, it is now turning to the search for peace and singing the praises of peace diplomacy, which the author would have liked to join in. However, the Seven Years' War can also serve as a reminder of when peace diplomacy has no chance. First and foremost, when even just one negotiating partner is already determined to go to war or to continue it and the negotiations are merely a pretence, as was the case not only at the time with Frederick, the trickster. Secondly, if the area involved is too large or the initiative comes at the wrong time and congresses and conferences become too confusing and cumbersome, as in the case of the Augsburg Plan of 1761. Diplomacy is urgently needed to end a war, however, and here intelligent bilateral agreements could be the more effective procedure if a politically unwise legal and moral marginalisation of the opponent does not impair the possibilities for communication, as was successfully avoided in the case of Frederick.

In terms of content, however, the restoration of the European world of states and, at that time, its incipient redistribution outside Europe is still - or is once again on our continent - the fundamental issue that is being fought over in war and peace, hopefully in the end with the prospect of a lasting political security architecture of peace.