Sono molti", "There are many". The first two words of Raphael's Epistola, which he possibly wrote to Pope Leo X between 1517 and 1519, sound like the incipit of a papal encyclical, a doctrinal letter: Ubi primum or Rerum novarum or Spe salvi and whatever they are all called. In reality, however, the roles are reversed: the artist is writing to his sovereign and admonishing him to fulfil his duty as guardian and promoter of culture; he reminds him of his responsibility for the preservation and study of ancient monuments.

The writer could assume that his addressee had the necessary level of education at the time to understand such a discourse. Leo came from Florence, where he was born in 1475 as Giovanni de' Medici and second son of Lorenzo de' Medici, known as the Magnificent, in the same year as Michelangelo. Not only did he grow up in the heyday of Florentine culture, but he also learnt from his father how closely art and politics are linked and that a high level of education is required in order to be able to deal with the responsibility of such a high office for culture and education in a qualified manner.

I.

Unlike many of today's politicians and leaders, rulers, even military leaders such as the papal commander-in-chief, Duke Federico da Montefeltre of Urbino, and not least the popes of the time, had a sense of this responsibility. Both historians and politicians are trivialising if they regard art and culture as a simple means of propaganda or measure them according to their material value or yield. Then we fail to recognise the social and moral role of architecture, painting, sculpture, music, literature, science and research, but also of manners, and misunderstand the need to promote them. Meanwhile, culture is often misused populistically through its commercialisation; without content, cultural management and marketing cannot promote culture. The decay and looting of Rome's buildings in post-ancient times, the destruction of Palmyra and Immerath Cathedral in the 21st century are rooted in very similar problems.

Of course, even in Raphael's time, some of the protagonists understood more and others less about culture, but they were generally sensitive enough to endeavour to do so. This in no way means that they were free of aggression, intrigue, exploitation and other negative character traits. - What a difference an educated pope makes to the cultural climate at all levels is something I experienced myself during the intermezzo of Benedict XVI's pontificate while working at the Vatican Museums.

I have already pointed out here that without culture, it is not possible to proclaim the Christian message. - Although Raphael laments the vandalism of Goths, barbarians and popes in his Epistola, he is far removed from any kind of undifferentiated identity politics; in a critical historical view and analysis of form, he even sees the new beginning of post-antique architecture with the "Tedeschi", the "Germans", in Gothic, because it makes "sense", "ragione".

Leo X had directly experienced the scope of art and culture under his predecessor. One striking example was the installation of the Belvedere's statue court around 1510. Following the example of Virgil's Aeneid, Julius II had formulated his programme here in a heroic vision in which ancient statues were assigned a specific role, as it were, independent of their conventional iconography, propagating an Augustan age as the ideal for his pontificate.

Julius had tried to stage his demonstration with the best antique statues: He contributed the Apollo from his personal collection; he acquired the Laocoon, according to Pliny the most outstanding work of art in antiquity, immediately after finding it and specifically purchased further statues such as the Venus Felix or the Ariadne as Cleopatra. Raphael was commissioned to depict this discourse in the fresco of Parnassus in 1510/11 on the wall of Julius II's private library, through the window of which one could look over to the Belvedere, the place where the Pope received his most important visitors in private audience: the deity, numen, Apollo, inspired the prophetic poet Homer, whose vision was passed on to the present day via Virgil and Dante.

On the wall opposite, Julius II had Raphael officially express his alliance with Giovanni de' Medici in intense portraits. Leo perhaps mastered the ability to use images for spiritual or political purposes even more than his predecessor and pursued it down to the last detail. Immediately after his election in March 1513, for example, he intervened in the ongoing execution of the frescoes in the Stanza di Eliodoro and the design of the encounter between Leo the Great and Attila in order to transform Julius II's political call to expel the French aggressors of the time from the Papal States with the motto "Out with the barbarians!" into a spiritual message.

From the pope, who had once vigorously opposed the king of the Huns, the action was completely transferred to the two apostle princes in heaven; Attila reacted to them, not to the pope. In what is probably his first official portrait after his coronation, Leo X becomes the peacemaker that he was hailed as when he was elected. The episode no longer takes place at the historic site near Mantua, where the border of the Papal States was to be secured; the new pope merely prevents the gates of hell from overwhelming the Church. For them, Rome stands symbolically as the "patria di tutti li Cristiani", "home of all Christians", manifested in the eternal symbol of the Colosseum propagated by Pseudo-Beda. A Roman aqueduct and one of the triumphal columns of Emperor Trajan or Marcus Aurelius define the city skyline.

II.

It is precisely the preservation of the monuments of this ancient Rome that is the subject of Raphael's Epistola to Leo X, mentioned in the introduction. It is preserved in three versions, the third of which, although not in his own hand but contemporary, is kept a stone's throw away from here in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. Based on a historical or art-historical discourse, it deals very specifically with the stylistic-critical, i.e. visual analysis, in which the development of ancient art from its Greek origins to its decline under Emperor Diocletian or Constantine is depicted, from which only architecture escaped.

It is in this context that the remarkable distinction between the stylistic epochs on the Arch of Constantine can be found; a silverpoint study of one of his reliefs is also in the Graphische Sammlung here in Munich. The critical but, as mentioned, thoroughly appreciative examination of Gothic architecture that follows in the Epistola is followed by a look at his own epoch up to Bramante. In the more theoretical part, in which the classical column orders are discussed, a method and the instruments used are described in detail alongside the study of sources, which enable the careful documentation of ancient buildings, as Raphael used them in his large-scale reconstruction of ancient Rome.

Leo X had thus commissioned an impressive scientific project, which Raphael carried out with an extensive staff. Nevertheless, the Epistola begins with an explicit warning to the sovereign and holds him to account by clearly reminding him of his responsibility for the important cultural assets.

Too many important buildings, remains and statues had been destroyed in the recent past, including the pyramid that had stood between St Peter's Basilica and Castel Sant'Angelo, which was regarded as the legendary tomb of the founder of Rome, Romulus, and almost played a legitimising role for Christianity in the iconography of the Martyrdom of Peter. Raphael also expressed this significance in his vision of the cross of Emperor Constantine, which he had designed for Leo X but was unable to realise due to his early death.

The complaint about the decay of Rome has almost become a topos since Hildebert de Lavardin in 1116 at the latest, and in the course of the 15th century, at least since Cencio de'Rustici's letter from the Council of Constance in 1416, the popes were included as those responsible. On the one hand, the drastic stories of iconoclasm told by Sylvester, Gregory the Great or Boniface IV play a role, but on the other hand, the destruction continued throughout the pontificates. Pius II, for example, kept a back door open in his own bull of 1462 for the personal looting of ancient monuments. The great losses under Alexander VI and Julius II were fresh in the memory.

Above all, however, Leo X himself had appointed Raphael as prefect in August 1515, who was to procure ancient marble blocks on a grand scale as building material for the new St Peter's Church and merely decide whether the value of any Roman inscriptions would prevent them from being reused. The trade and destruction of the antique heritage thus continued, and it was precisely against this that Raphael took the initiative in his Epistola. The Sienese architect Francesco di Giorgio Martini, who died in 1501 and was one of the most universal artists of the 15th century, who experienced the Roman ambience from the outside, so to speak, had already attempted to counter such "barbarism" with a programme in which he wanted to preserve the ancient monuments at least in architectural recordings.

Leo's personal commitment to artistic matters could be very impressive and at times nuanced. Exactly one year after his election to the Chair of Peter, Bramante, the master builder of the new St Peter's Church, died on 12 March 1514. Whether his death was due to illness or an accident need not be discussed further here. In any case, Bramante "moriens" had recommended Raphael to the papal architect as his successor.

Despite his obvious appreciation for both personalities, the Pope did not blindly follow the legacy of his architect. After two weeks, Leo only appointed the thirty-one-year-old as provisional director. He then held daily meetings with him and the almost eighty-year-old Fra Giocondo, Bramante's magister operis, in order to familiarise himself with the subject matter; it was not until 1 August that he was apparently convinced to appoint Raphael as master builder of St. Peter's.

It was more or less in this context that Raphael - probably together with his friend, the Mantuan ambassador Baldassare Castiglione - wrote his Epistola. Regardless of whether Raphael was aware of Francesco di Giorgio's earlier appeal, the Sienese artist's sketches of antiquity remained relevant in his studio even after his death. Leo X was evidently so cultured that he was able to understand the issue and so sensitive that it was worth bringing it to his attention. Raphael, not least in his role as prefect for the procurement of antique marble, felt the need to address the pope's responsibility explicitly and critically. Unfortunately, neither the intended purpose of the letter is known, nor whether the thoughts, whose final form we do not know, ever reached Leo.

III.

Apparently, Raphael had already travelled to Rome a second time in 1506 or 1507 before moving there for good in 1508. His lifelong fascination with the central Roman building of the Pantheon can be traced back to this second visit at the latest. His last wish was to be buried here in an aedicula restored from his estate. While he Christianised this aedicula with a statue of the Madonna, in his early study he had freed the antique interior from all the medieval fixtures of the Christian altar and reconstructed the original antique impression in drawings.

After his final move to Rome in 1508, he created his own pantheon as a funeral chapel for the papal banker, Agostino Chigi from Siena, perhaps the richest man in the world at the time, around 1512, in which he was able to continue the style of the impressive model right down to the subtle architectural ornamentation and the precious antique marble incrustations, including the enormous block of rare Africano as a threshold. Above all, the materials were a decisive factor for him in recreating classical antiquity.

Raphael's interest in the Pantheon never waned; he studied it on site or by copying building photographs from friends or colleagues. The comparison of a sheet in his own hand with further studies in a codex from his workshop gives an idea of the dynamism and curiosity in his environment. With Raphael's tomb, the restoration and transformation of an ancient monument became his last work, and it is not surprising that on 6 April 1520 his contemporaries mourned not primarily the death of an inspired painter, not the death of a brilliant architect, but the death of a gifted scholar who understood antiquity.

In his painting, Raphael creates unexpected sensory impressions in the viewer. I am thinking here of the intensity of his portraits in the stanzas, with which the painter depicts over fifty personalities at the papal court, from cardinals to grooms, e.g. Cardinal Raffaele Riario in his fresco of the Mass of Bolsena from 1511. This also applies to the abstraction of light, as suggested by the candles and oil lights with the smoke surrounding them, which flicker on the altar of sacrifice of the high priest in the temple of Jerusalem during the expulsion of Heliodorus.

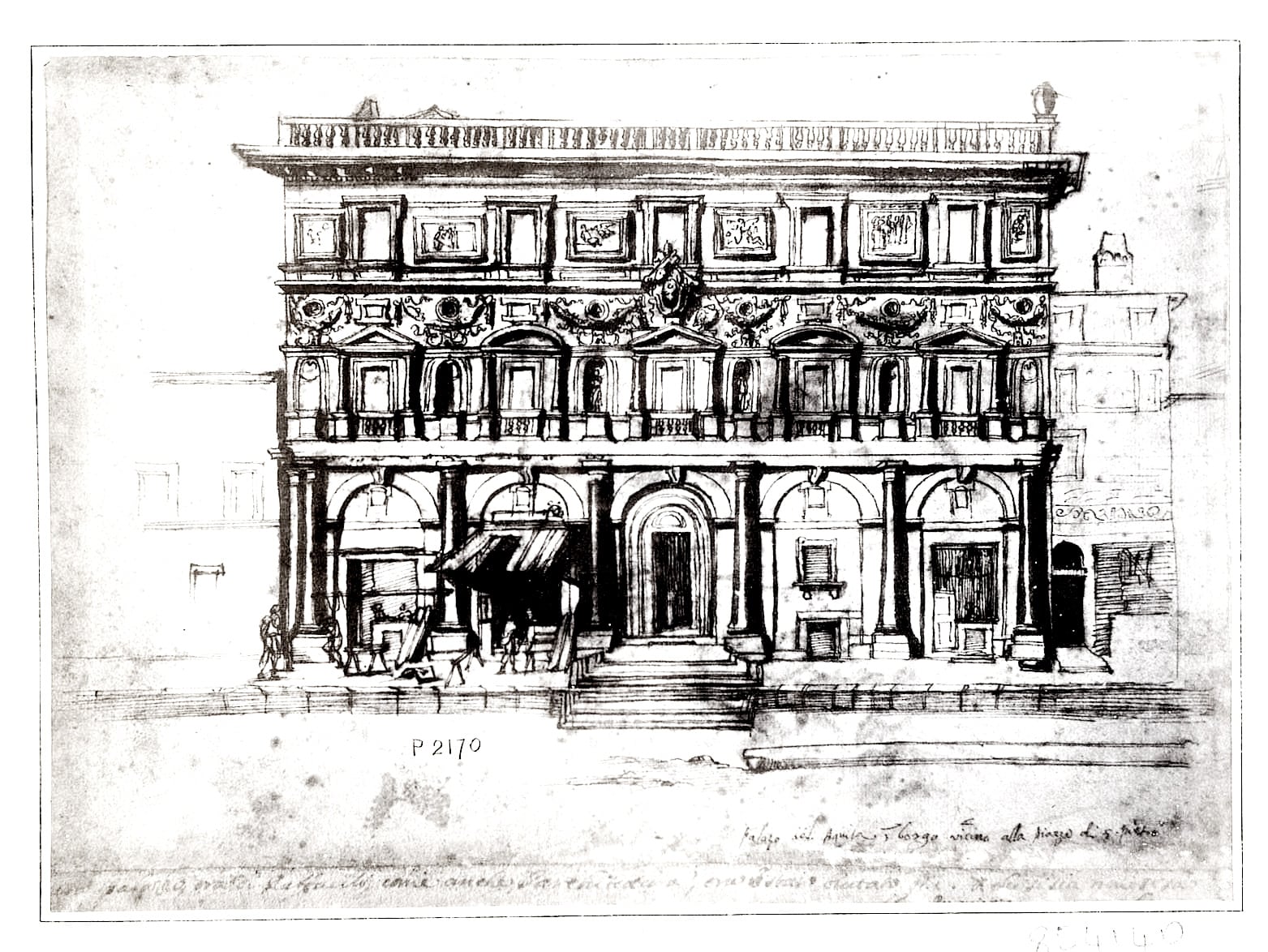

In his architecture, Raphael enlivens his elevations by playing with a classical structure. In Palazzo Branconio, by bringing the order down to the basement, he opens up the façade and invites passers-by to enter; he begins a multifaceted dialogue with polychromy, stucco and paintings. On the one hand, Raphael's artistic virtuosity heightens the viewer's sensitivity to seeing; on the other, he himself possessed a subtle ability to see that enabled him to make highly differentiated scientific observations, so that he also taught people to see in this particular way.

Therein lies a fascination with Raphael's archaeology. Perhaps most impressive is his aforementioned stylistic criticism of the Arch of Constantine in Rome, with which he was able to distinguish the spolia from the Constantinian architectural elements, but with which he was also able to date the relief decoration to the Trajanic, Antonine and Constantinian periods of origin, as is still the archaeological doctrine today. From this analysis, he drew conclusions about the Constantinian period, thus methodologically following in the tradition of the ancient Greek historian Thucydides from the fifth century BC or the Eastern Roman scholar Manuel Chrysoloras from around 1400 and preceding Johann Joachim Winckelmann and the archaeologists who followed.

Bramante had evidently already recognised this quality of Raphael's eye, which was capable of subtle differentiation, during his stay in Rome in 1506/07, as he appointed him as an arbiter to decide the competition between four sculptors for a replica of the Laocoon, which had just been excavated at the time.

Ancient sculpture fascinated Raphael throughout his life. Around ten years later, he sent his colleague Giovanni da Udine to the Quirinal to measure the colossal horse of the Dioscuri group and enter the measurements into a red chalk drawing in his own hand. This was his pragmatic approach to his studies.

Raphael repeatedly drew on this profound knowledge. For example, in the vision of the cross of Emperor Constantine, which he designed in 1519/20, he relocated this turning point in the history of Christianity over the tomb of Peter by showing the ruinous topographical situation of the Roman Field of Mars as seen from the Vatican with its reconstructed buildings. In this way, he figuratively adds further legitimisation to the papacy.

Similarly, he developed the reconstruction of the destroyed parts of the Arch of Titus from his stylistically differentiated knowledge of ancient architectural ornamentation. This profound expertise was generated, among other things, from the artist's private collection of antiquities. A drawing by his pupil Giulio Romano, for example, proves that Raphael had an Ionic base, a rarely occurring ancient architectural detail that is described in this form by the ancient architectural theorist Vitruvius.

IV.

I would at least like to briefly mention the translation of Vitruvius' Latin architectural treatise, which Raphael personally commissioned from the old Marco Fabio Calvo and which is also part of Munich's local colour and is kept in the Bavarian State Library. Raphael added marginal notes to it in his own hand and obviously planned an illustrated Italian edition. All of this sheds light on his multifaceted education, his wealth of ideas and his multifaceted creativity in all his areas of activity. But it also shows a young man of boundless commitment who, through his own example, was able to inspire not only the rich and ruling classes, but also, according to his contemporaries, his social environment, the people in his workshop and his friends.

Raphael's analytical approach in his preoccupation with antiquity had evidently remained in his consciousness. As early as 1755, Johann Joachim Winckelmann was aware that Raphael had employed draughtsmen in Greece to document ancient paintings and buildings, as Winckelmann stated in his first work Über die Nachahmung der Griechischen Werke and could read in Vasari's biography of Raphael. Winckelmann, who incidentally developed his most famous dictum of the "noble simplicity, quiet grandeur" on Raphael's Sistine Madonna and only in a second step had it unhesitatingly redirected to the antique sculpture group of the Laocoon, also found that one must be "familiar with the antique works as with a friend"; he saw this as a characteristic of Raphael.

Despite everything, Raphael's preoccupation with antiquity did not result in classicism. Perhaps his relationship to antiquity can be summarised with a metaphor: Leonardo advised the artist to soak a sponge in paint, throw it against the wall and let the stain and the drops running down the wall stimulate his imagination. Antiquity seems to be Raphael's sponge, which he fills with his studies and from which he can genuinely draw.

Three large-format compositions, which are dominated by female figures and place lively children in the foreground and which Raphael painted almost simultaneously in 1512, may illustrate this. The Madonna di Foligno and the Sistine Madonna may even have met in the painter's studio, as one was apparently just finished and left the workshop when the commission for the other arrived. However, the third "grace" in this roundelay is a mythological figure, as the fresco of Galathea was also painted in Agostino Chigi's villa at the beginning of 1512. Just as Raphael created the Chigi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo from an understanding of the ancient Pantheon, Galathea and the Virgin Mary triumph in the same heaven.

While the juxtaposition of these three female figures in a reduced, almost abstract manner can make clear how much antiquity was part of Raphael's nature, his Madonna under the Oak may show how virtuosically, almost lavishly, he could sparkle with antiquity. I will not comment in detail on the composition with its complexity of space, figures, landscape and accessories, but only address the playful handling and point to some completely heterogeneous sources that were available in the studio in the form of drawings: The Madonna, developed from an ancient matron and seated at an angle in the picture, leans on a neo-Attic candelabra base, which Raphael has enlarged and adapted in its proportions, while he has extremely reduced the proportions of the composite base with its subtle architectural ornamentation, which originates from the enormous Temple of Mars Ultor on the Forum of Augustus, to the necessary scale. The two ancient buildings beyond the hills are simply taken from two opposite pages of one of his drawing books.

Raphael not only integrated materials that he had collected in drawing form or as objects in his workshop into his creations during the design process, he also intervened pointedly in his reception by means of his own studies. For example, he developed the Judgement of Paris, which he had engraved in copper by Marcantonio Raimondi, based on an antique sarcophagus and not only "transformed" the central scene with his own nude studies. Printmaking is an important area of Raphael's oeuvre in many respects.

In other cases, he evokes a freely invented antiquity, such as in the cartoons for the tapestries in the Sistine Chapel. As part of an investigation using digital technologies, we are attempting to interpret Raphael's fantasy antiquity, among other things.

V.

Artists are always a challenge, sometimes because of what they say, but above all because of what they can do. By choosing viewers, clients, etc., they reveal their own quality. This choice is as much a risk as an artistic creation. The responsibility of a ruler or a society lies in its openness to this dialogue and in its dynamics; anyone who bans or dismisses artists or negates their works, on the other hand, makes themselves untrustworthy.

To the same extent, society has an obligation to ensure that culture is accessible and maintained: this applies to different areas, such as the public space in which we live, even if it is not the venerable ruins of ancient Rome. It concerns access to museums, and increasingly even to churches, especially for young and less well-off people; it concerns, above all, the excessive cost of the Entree ticket, the copyright that restricts the free use of our visual culture - including both our Raphael monographs - and other stumbling blocks. Raphael's appeal could not be more perverted than by an EU poster: the aim of saving the ruins of Pompeii cannot be to promote tourism.

Museum advertising by the coffee shop mocks his admonition to the Pope. His explicit appeal to Leo X to preserve and research the antiquities of Rome was not about valorisation, i.e. a commercial enhancement of culture. When he laments the collapse of an ancient building because the Pozzuolan earth was to be excavated for new buildings underneath, this has already become a metaphor for the way we deal with cultural assets today.

Raphael has emphasised an appeal through the virtuosity of his own art. The consensus that the events and exhibitions to mark the 500th anniversary of his death two years ago (the pandemic prevented the event from taking place in 2020; editor's note) have demonstrated and continue to demonstrate throughout Western culture, from St Petersburg to Stendal to London and from Dresden, Città di Castello to Naples, show that his appeal is not dead even after 500 years, but is still necessary and generates hope.