We look with admiration at the great deeds that some people accomplished and yet only achieved through the favour, help and cooperation of many others. I am thinking, for example, of rulers of nations who, as heirs and successors in the empire of their fathers, extended their rule with the arms of subordinate peoples, such as Alexander, Julius, Augustus, Charles and many others, whose deeds have provided rich material for the historians of past times" (transl. Kallfelz, c. 1).

I.

This is how Balderich of Trier introduces his Gesta Alberonis archiepiscopi Trevirensis, written between 1131 and 1157, which describe the life and deeds of Albero, who served as Archbishop of Trier between 1132 and 1152. In order to adequately portray the work of his protagonist, Balderich goes to great lengths to make it clear that even Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Augustus and Charlemagne were ultimately only able to create their empires with the help of others. This is the backdrop against which he sets Albero himself in his epoch, which he describes as follows: "It was in that stormy time when kingship and priesthood were at loggerheads with each other, that conflict that had begun in the days of Pope Gregory VII, who had previously been called Hildebrand, and Emperor Henry III, continued under Popes Urban and Paschal and lasted until the time of Pope Calixt" (ibid.). Balderich thus outlines roughly what has also been the subject of the previous contributions. However, he then offers a rather idiosyncratic interpretation of the investiture dispute, stating that the cause of the conflict lay in the fact that Henry IV (1053-1106) had sold episcopal churches - this, and not investiture, which had been exercised by the Roman-German kings "with the permission of the Roman chief shepherds" since the days of Charlemagne, had led to a conflict between pope and king.

As individual as this interpretation of the Investiture Controversy may be, there can be no doubt that Balderich perceived it as a fundamental upheaval, which he places in the context of the emergence of world empires with a view to the actions of his protagonist Albero of Trier. He characterises it as a fundamental conflict for the further development of christianitas and beyond. Nevertheless, it should be noted that as broad as Balderich's horizon seems to be when categorising the Investiture Controversy in world history, his perspective on the conflict itself is just as limited. If we stick to Gerd Tellenbach's definition of the Investiture Controversy as a "fundamental struggle between secular and ecclesiastical powers for the right order", which is still used in standard reference works today, it is clear that this fundamental struggle did not only take place in the empire, even if it was particularly fierce there.

If we understand it as the aforementioned "struggle for the right order", then it is a European phenomenon. The Investiture Controversy was not limited to the empire north and south of the Alps and changed the relationship between spiritual and secular power in Latin Europe. In Tellenbach's general perspective, the central fruit of the Investiture Controversy was a conceptual separation of the spiritual and secular spheres, which became characteristic of Latin Christendom. This was no small thing and became the basis for the further development between regnum and sacerdotium throughout the pre-modern period. This was not a general and sharp distinction between secular and sacerdotal power in the reality of the lives of contemporaries, both clergy and laity. Both were closely interwoven even after the Investiture Controversy - and clerical and secular protagonists were in favour of this connection in principle. It remained a defining feature of the entire pre-modern period. The central fruit was therefore not the actual separation of the two spheres, but their conceptually sharper definition and demarcation from one another.

The real intertwining of the two was nowhere more evident, even for the maintenance and functioning of the official church, than in the material endowment of ecclesiastical offices. Almost every ecclesiastical office, every officium, was associated with an economic endowment. The holder of the office, for example a priest, also received an economic provision along with the office. The idea behind this link was that the priest should be able to devote himself unhindered to his duties as a pastor - which is why he should be nourished by the possessions of the church.

The landlords, who had built churches on their land and endowed them with other properties, had always demanded a more or less pronounced say in the appointment of the priestly office on the basis of this material endowment. In the social practice of the era, ownership of the church was linked to the holder of the office. There was always an appointment to both the spiritual office and the associated secular property at the same time. The conceptual separation of the two - the officium and the possessiones - led to a distinction being made between the officium and the possessiones from the end of the 11th century onwards. One appointment was theoretically a purely ecclesiastical matter, the other theoretically a purely secular one.

However, the concrete organisation of the appointment of a priest to a parish and the associated benefice remained largely unaffected by this conceptual separation. But it prepared the way for an even more fundamental separation, which the canonist Ivo of Chartres then carried out around 1097, the separation into temporalia and spiritualia, into spiritual and secular matters. It was a general separation that applied to the entire christianitas.

Despite the European dimension of the investiture dispute, this article focuses on the empire, ending with the Concordat of Worms of 23 September 1122, which regulated the conditions for the appointment of bishops and the elevation of abbots. Although the terms temporalia and spiritualia do not appear in this treaty, the conceptual separation of the two areas is clearly recognisable. This is all the more true as the symbols of investiture are now also separated: Bishops and abbots were invested in the temporalia in the Roman-German Empire after the end of the investiture dispute with the help of a sceptre, whereas the ecclesiastical side continued to use the traditional symbols of ring and staff to invest in the spiritualia. The conceptual separation of officium and possessiones was thus also realised in the empire and expressed in new symbols.

II.

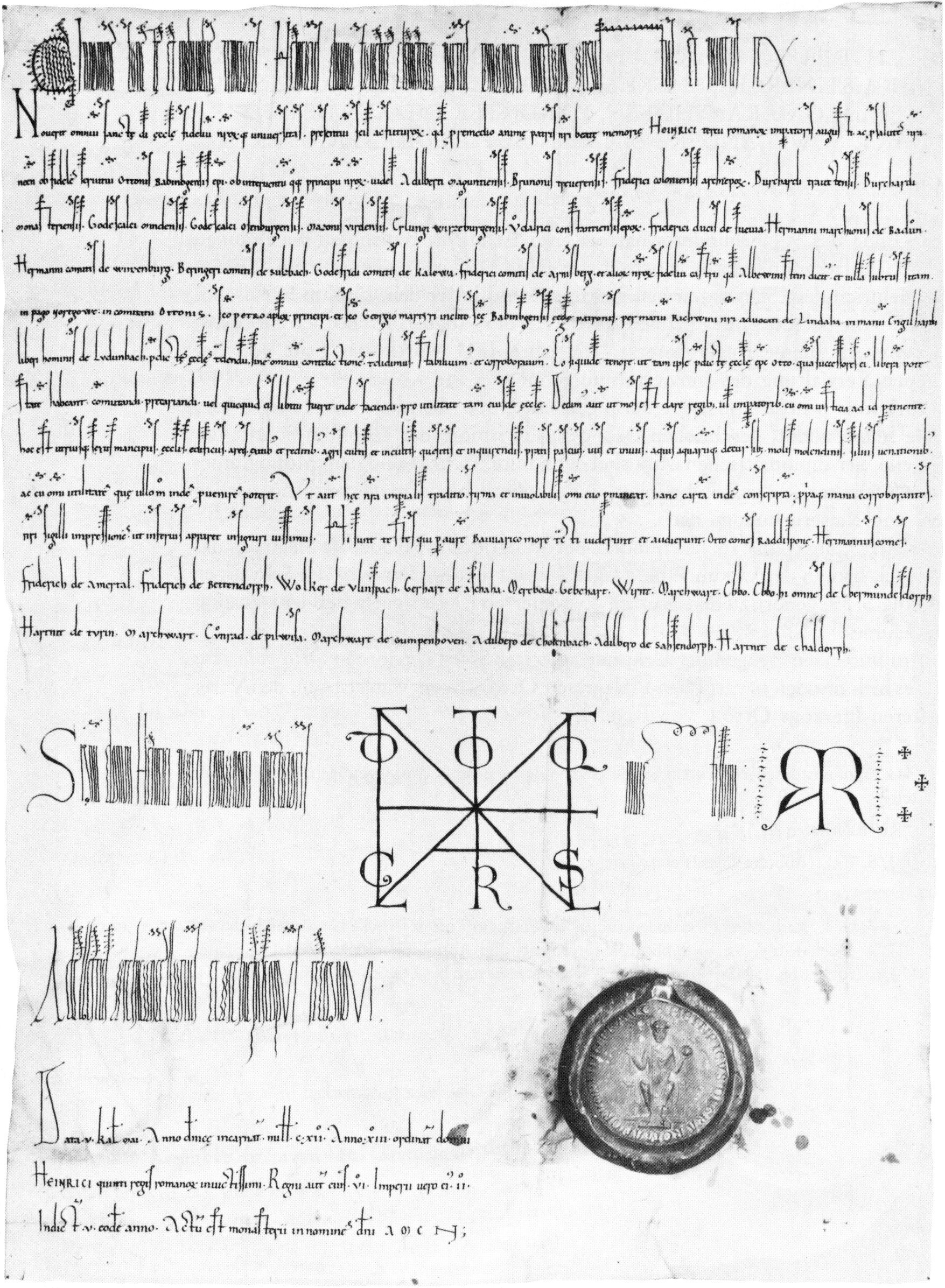

But what exactly did the Concordat of Worms, which was concluded between Emperor Henry V (1106-1125) and Pope Calixt II (1119-1124), regulate? The term initially suggests a comprehensive set of rules. However, this term is not a self-interpretation of the agreement between the emperor and the pope, but a research term that is somewhat misleading. This is because one of the peculiarities of high medieval treaties is that they were not a jointly drawn up contract that both parties signed and thus gave it validity. No, each party had a separate document drawn up: Henry V issued a privilege, which we refer to as the Heinricianum after the issuer, and which is still preserved in the Apostolic Archives in Rome. And Calixtus II, Henry V's papal contracting partner, also issued a document, although only copies of it have survived and it is known as the Calixtinum. The fact that the papal document has not been preserved in the original is somewhat perplexing when you consider that the Concordat of Worms is generally considered to have ended a decades-long dispute, a fundamental struggle, at least for the empire.

The astonishment at the form in which the treaty was concluded is heightened when one considers the external form of the Heinricianum. Even for students of medieval history, it is always astonishing how unspectacular the document is that ended the investiture dispute in the Roman-German Empire. It is an almost square piece on which eleven lines are written evenly spaced. It lacks all the usual decoration of a royal charter.

According to the rules of the royal chancellery, every royal and imperial charter begins with a so-called Chrismon, an ornate C, which symbolically expresses the invocation of Christ as the beginning of the ruler's actions to be recorded in the document. The Heinricianum also lacks any other form of solemn or even deliberate design, apart from the slightly larger line spacing. The name of the ruler is not emphasised. The elaborately designed signs of recognition or the monogram of the ruler, elements which at first glance distinguished the documents from simple documents and also served as a safeguard against forgery, are missing.

And by 1339 at the latest, the seal of the Heinricianum, which according to a report in the Liber Pontificalis, the papal book on the life and deeds of the respective popes, is even said to have been a gold seal, was also lost. In short, all the elements by which the king normally staged himself and his reign in a royal charter are missing from the Heinricianum. In other words, the Heinricianum is in no way recognisable as the document that is supposed to have ended a decades-long dispute.

The fact that the Heinricianum is actually a document can ultimately only be recognised by the signature of the Archbishop and Archchancellor of Cologne, Frederick, at the end of the document. Why the imperial side attached so little importance to the form of this document is still unclear today. From the perspective of the Treaty of Ponte Mammolo of 11 April 1111, in which the Salian Henry V had extorted considerable concessions regarding royal investiture rights from Pope Paschal II (1099-1118), whom he had taken prisoner, the solution of the Concordat of Worms was a clear restriction of royal rights. Did they not want to enhance this loss of face with an attractive figure?

Generally speaking, the secular side of treaties in the High Middle Ages attached less importance to a written record than to oral proclamation - was the written document therefore not so important for the imperial side? Or was the specific document not so important to the imperial and papal side, but did their interests lie in something completely different? We will come back to this later.

Firstly, I would like to go into the content of the Concordat of Worms very briefly. Its regulations were not only intended to apply to Emperor Henry V and Pope Calixt II, but also to their successors beyond their terms of office. In accordance with the differentiation between temporalia and spiritualia, Henry V renounced the investiture of bishops and abbots with ring and staff. This is the very first point of the Heinricianum, and it is not just a ceremonial regulation, but is of great importance. The Salian thus renounced the use of an ecclesiastical symbol of investiture. This was to be reserved exclusively for the clergy.

Translated, this meant that the king was no longer involved in the investiture into a spiritual office. The appointment of a shepherd to his office had thus become a purely ecclesiastical matter. The second point, the assurance of canonical election, also serves this purpose. As a rule, this meant that the election was to take place according to an old formula clero ac populo, by the clergy and people of a diocese. But what this meant in concrete terms, who exactly was meant by clergy and people, varied greatly from case to case. It was not until the end of the 12th century that the election of the bishop in the Roman-German Empire was actually standardised and in fact only rested with the cathedral chapter. Until then, however, there were very different forms.

At the end of the investiture dispute, however, the free and canonical election meant above all an election without the decisive influence of the laity, without coercion from outside. And finally, the emperor promised to support the pope in regaining the Regalia sancti Petri, in short, the possessions of St Peter, from which the Papal States developed under Pope Innocent III (1198-1216).

The Calixtinum, which has not survived in the original, contains the Pope's concessions to the emperor as head of the universal church. It conceded to Henry V that the election of a bishop or abbot had to take place in presentia regis, in the presence of the king. Furthermore, the king had the right to decide on the advice of the metropolitan and the suffragans in the event of an ambivalent choice. The wording reads saniori parti assensum et auxilium praebeas, he may grant his consent and assistance to the better part. This gave the king considerable room for manoeuvre, not least because he could decide what was an ambivalent election and who was the sanior pars.

The last point was the investiture with the regalia, the royal possessions, which had formed a significant part of the economic basis of the imperial bishoprics and imperial abbeys since the Ottonian period at the latest. As already mentioned, investiture into the regalia was to take place with the symbol of the sceptre, in Germany before the consecration of the elector, in Italy and Burgundy at the latest six months after the consecration. North of the Alps, investiture into the regalia therefore had to take place before the consecration; south of the Alps, it was a consequence of the consecration.

III.

At first glance, one might think that the king had basically been deprived of any influence on the appointment of ecclesiastical offices. But this was not the case. Often enough, the electoral college did not agree and appealed to the ruler, who was then able to make a decision. Investiture in the regalia also offered the ruler considerable potential for threat.

This was not an abstract regulation, but had very concrete consequences, which I would like to illustrate by way of example: Frederick Barbarossa (1153-1190) used this leverage in his disputes with Pope Alexander III (1159-1181). A papal schism had broken out in Rome in 1159 and both candidates, Victor IV and Alexander III, were trying to gain the widest possible recognition. Barbarossa had quickly decided in favour of Victor IV and wanted to prevent Alexander III from being recognised in the empire. He therefore refused to appoint the bishops of the ecclesiastical province of Salzburg, who were almost unanimously on the side of Pope Alexander III, whom Barbarossa did not recognise, to the Regalia. Instead, he had these administered by imperial appointees, which led to a painful reduction in the bishops' economic options.

The election of bishops could also still be influenced by the king, as can be seen in the elevation of the archbishops of Cologne from the family of the Counts of Berg. This example clearly shows that the definition of a free and canonical election was not simple and that the king's influence was still considerable if the electors were not in agreement. In Cologne at the end of 1131, almost ten years after the Concordat of Worms, two candidates and their family associations faced each other: On the one side, Bruno from the family of the Counts of Berg; on the other, the Xanten provost Gottfried von Cuyk, whom the family of the Counts of Are supported.

The conflict began with the fact that it was unclear who could elect the archbishop. This right had previously been exercised by the Cologne College of Priors, an association of the Cologne priories, including St Cassius in Bonn. The role of the clergy in the election by the clergy and the people was therefore performed in Cologne by the college of priors - in most episcopal churches of the empire north of the Alps, however, it was the cathedral chapters that acted as the electoral body. The college of priors finally elected Gottfried von Cuyk at the end of 1131 and he expected to be appointed to the regalia in December 1131, when King Lothar III (1125-1137) came to Cologne, as provided for in the Concordat of Worms.

However, Bruno von Berg's party had not yet admitted defeat. On the contrary, they announced that the election had not been unanimous, which was the ideal of every medieval election. Conversely, it could also be said that the election was ambivalent, as a small group who considered themselves to be the sanior pars declared that they could not agree with Gottfried's election. Lothar III seized the opportunity - and intervened in the election. Formally, he could cite two reasons for this, which had been stipulated in the Concordat of Worms: The election had not taken place in the presence of the king, which contradicted the Calixtinum, and it appeared to be an ambivalent choice, as part of the college of priors supported Gottfried, while another and the cathedral chapter supported Bruno of Berg.

Lothar finally opted for Bruno (1131-1137), who was then elected archbishop in the presence of King Unanimiter on 25 December 1131, subsequently appointed to the Regalia and consecrated by Cardinal Bishop William of Palestrina on 18 March 1132. The Concordat of Worms was therefore by no means the end of royal influence on the occupation of bishoprics and abbeys. The influence of the laity on the lower churches, simple parishes, continued to exist even beyond the kingship, not least through the legal instrument of the right of patronage, which cities, for example, exercised for positions at churches in their urban area. The Investiture Controversy was therefore by no means the end of the influence of the secular side on the appointment of ecclesiastical offices. It only led them into clearer channels and also limited them in some areas.

Older research repeatedly spoke of the end of the sacral kingship, which had come with the Investiture Controversy. However, this interpretation, like the sacral kingship as a whole, has been increasingly scrutinised in more recent research. The conditions for exercising influence over the Church had certainly not become any easier for the king as a result of the Investiture Controversy. However, there are no statements by the kings themselves or by other individuals that note a de-sacralisation of their office. It is certainly important to realise who attributed a sacral aura to the king and by what will. If the king is described as the protector of the church, this may conceal the idea of a king who is supposed to rule over the church, but it is much more likely that church princes were asking the king to do something with this description of the royal position: they asked the king for protection by declaring the king to be their patron in their own interests, for example to ward off the desires of nobles, and wanted to make him part of the church.

From the perspective of the reformers, Henry IV's penitential journey to Canossa therefore did not represent a turning point. The interpretation that kingship was humiliated by the papacy in Canossa does not date back to the 11th century and is more of a romantic idea and then above all a motif taken up in the cultural struggle of the 19th century, when Protestant Prussia confronted Pope Leo XIII. But this is a later exaggeration of the events of Canossa. Canossa did not bring about a change in fundamental thinking about the king and his powers. In this respect, the Investiture Controversy was probably not a fundamental upheaval - only the representation of royal rule and this rule itself changed.

Gregory VII's (1073-1085) statements on royal power, which were characterised by disappointment and even hatred, and which he wrote in his famous letter VIII/21 to Bishop Hermann of Metz after the second excommunication and deposition of King Henry IV on 15 March 1081, left no sacred component to kingship. According to Gregory, all secular power was reprehensible and kings did not strive for good coexistence and the fulfilment of the Christian commandments, but were part of the diabolical body (illi vero diaboli corpus sunt). This was written by the pope who had excommunicated Henry IV for the second time, but who had become increasingly radicalised and with whom no one wanted to have anything more to do five years later, after his expulsion from Rome. His ideas had become too radical - people no longer wanted anything to do with this religious zealot.

And yet should his unrealistic effusions about worldly violence have remained effective? This cannot be assumed. Moreover, one has to ask whether there was a sacred kingship at all that could be de-sacralised by the Investiture Controversy. Is it conceivable that the father of Henry III (1039-1056), Conrad II (1024-1039), was perceived as a full layman who did not appear in the sources as a sacral ruler, and that his son then suddenly became the epitome of sacral kingship? Or are these not just the ideas of some clergymen who would have liked to see Henry III as such? I am deliberately emphasising this in order to make it clear that things can certainly be seen differently, but that the upheaval caused by the Investiture Controversy was not as great as older literature has sometimes described.

IV.

If we ask about the results and consequences of the Investiture Controversy for the Church and the Empire, the apparent sacrality of the ruler was probably not affected. Nonetheless, the end of the Investiture Controversy brought about a considerable upheaval in the direction of royal rule, as can be seen from the Concordat of Worms itself. Let us return to the decidedly simple form of the Heinricianum and the question of why the document that ended a decades-long dispute is so conspicuously inconspicuous. The Concordat of Worms was not unimportant - contemporaries in the Empire and beyond were aware of its contents, which also left a broad historiographical echo.

However, if one looks at the sources that report on the realisation of the Concordat of Worms, the exact contents of the Heinricianum and Calixtinum are barely mentioned. Rather, what is emphasised and vividly painted is that the decades-long dispute had now come to an end, that there was once again cooperation between the papacy and the empire, cooperation between the two universal powers. This was evidently much more important to contemporaries than the precise regulations of investiture, which, despite the separation of the spiritual and secular spheres, left the ruler with sufficient scope for intervention.

For contemporaries, it was not the question of investiture that was the main subject of the Treaty of Worms, but the agreement between the two universal powers to work together again from then on. This was the decisive factor for bishops, abbots, clerics, dukes, counts and other laymen. The time of the fundamental struggle for the right order was over - at least in its familiar fierce and fundamental form. A new working basis had been agreed upon.

This could also explain why the Heinricianum was given this simple form, which looks more like the writing of a verbal agreement and less like a pompous ruler's diploma. The paintings in the Lateran Palace, where the pope resided until the beginning of the Avignonian era with the departure of Pope Clement V (1305-1314) to the south of France in 1309, could also indicate that this view was also shared at the papal court. The medieval popes did not reside in the Vatican, which was only expanded into a real papal residence by Innocent III at the beginning of the 13th century, but at St John Lateran - and to this day St John Lateran is the episcopal church of the Bishop of Rome.

Practically nothing remains of the former Lateran Palace. It is said to have fallen into disrepair at the end of the 14th century. However, drawings of the murals in Calixt II's consultation rooms by Onofrio Panvinio, who died in 1568, have survived. These are therefore modern sketches of what Panvinio was still able to see of the dilapidated rooms of Pope Calixt II, who had concluded the Concordat of Worms. The paintings have repeatedly been described as the apotheosis of the reforming papacy - a purely academic term that is taken neither from the paintings themselves nor from contemporary reports about them.

What do you see? Popes are each seated on a throne. In the chronological order of their pontificates, we first see Pope Alexander II (1061-1073) and under his throne an antipope, Honorius (II), the former Bishop Cadalus of Parma, depicted as a stool. The depiction alludes to Psalm 110:1, which reads: "Thus says the LORD to my Lord: Sit at my right hand and I will put your enemies under your feet as a footstool." This is how popes and antipopes are depicted. Alexander II is followed in chronological order by Gregory VII, with Clement (III) as the footstool under his throne - another antipope. And this narrative in the form of popes enthroned above antipopes in the form of stools is continued via Paschal II to Calixtus II, at whose feet Gregory (VIII) can be seen, who was elevated to antipope by Emperor Henry V in 1118.

The series of antipopes supported by kings that began with Cadalus-Hono-rius (II) thus continued into the lifetime of Calixtus II, who had these paintings made. Calixt overcame his opponent and had himself and his predecessors, who struggled with other antipopes, depicted in a row. The entire painting repeatedly shows a pope who has overcome another pope. The viewer is shown a schism, a split in the church - in which one side considered one pope to be the rightful pope and the other side the other pope. Only in retrospect did the one of the two pretenders who lost become the antipope and the one who prevailed become the rightful pope in the line of popes.

But what does this series of popes who overcame an antipope have to do with the co-operation between pope and emperor? The answer can only be found by taking a closer look at the reasons for these schisms: All the defeated popes to be found in the paintings of the Lateran Palace, who in retrospect became antipopes, had been supported by the Roman-German kings. In other words, these schisms had only occurred because the king had supported the later defeated counter-candidate.

had supported.

The fact that the emperors had played a decisive role in this in the eyes of Calixt II is made clear by the last person depicted in the series of popes and embezzled antipopes. This last person depicted is not a pope, but Emperor Henry V. Calixt II and Henry V hold the Concordat of Worms in their hands, as if promising that this long series of popes and counter-popes supported by the emperor has now come to an end and that the two universal powers will once again work together in harmony. The dimensions of the depiction of the piece do not correspond to the original of the Heinricianum, which is still preserved in the Vatican's Apostolic Archives, but this was clearly not important to contemporaries. The decisive factor was the forward-looking message of these paintings: The time of schisms was over and the universal powers were working together again.

The pictorial programme, at the end of which the Concordat of Worms was signed by the pope and the emperor, therefore does not show any investiture issues, but only the result of a dispute between the emperor and the pope - the emergence of schisms. From the papal perspective, this was also the decisive aspect of the Concordat of Worms: the end of the dispute and the future cooperation of the universal powers. In the eyes of contemporaries, this was a fundamental upheaval that would enable the Church - well beyond the Empire - to once again fulfil its true purpose of mediating divine salvation.

This core regulation of the Concordat of Worms, which had been concluded between the empire and the curia, had an impact on the universal church, as the Roman church had become more and more universal through its universalisation, which had taken place from the middle of the 11th century. The ecclesia Romana had become the ecclesia universalis - the papal schisms promoted by the Salian kingship therefore had an impact on the entire church. In a sense, the Concordat of Worms signalled nothing less than the beginning of an era of peace for the Church - at least that was the plan.