The topics of freedom of expression and censorship have lost none of their explosive nature today. They even seem to be gaining in relevance in view of the current crises around the world and in the centre of Europe: democracies are eroding due to populist tendencies, while autocratic and dictatorial systems are gaining strength.

The following article poses very basic questions about censorship and provides an overview of the subject area and the current state of academic research. It begins with a brief outline of the history of censorship as a history of communication (1), followed by a discussion of the terminology, straddling the formal and informal concept of censorship (2). An attempt to systematise the phenomenon of censorship (3) is followed by a brief outlook on a current handbook project on global censorship research (4).

Censorship and communication

What is censorship and how long has it been around? The term 'censorship' itself originates from ancient Rome, even though the matter itself is much older and has already demonstrably shaped early cultures, "from early Sumeria and Egypt to the controls built into Chinese ideography, as well as the taboos and protocols maintained around symbolic meaning in numerous other societies".

Generally speaking, censorship can be defined as the control and restriction of communication - and it has actually always been there. As an omnipresent, worldwide phenomenon, it has characterised human cultures from their beginnings to the present day. Communication and its control cannot be thought of without each other; and it is precisely in this sense that censorship can be understood not only as destructive, but also as productive: In a certain sense, it creates communication and thus society in the first place by defining and limiting spaces of discourse, by co-determining literature and the public sphere. As Ulla Otto puts it, censorship is a "historically parallel and subsequent phenomenon of literature" - although one should rather speak of communication in general. This is what Beate Müller, for example, does, describing "all communicative expressions intended for an audience, whether written or oral, visual or acoustic" as potentially affected by censorship and therefore listing other areas and media in addition to literature (in a somewhat unsystematic order), music and the performing arts, science and teaching, theatre and film, print media, radio and television; digital media should be added here.

If we assume a certain coexistence, perhaps even co-evolution, of communication and censorship, then a look at history reveals three focal points in this intricate relationship: The great media upheavals in the history of communication and knowledge were each accompanied by a change and growth in censorship. This is not surprising: all of them - the shift to written language, to print and to digitality - enabled a more extensive or more permanent form of communication in terms of time and space.

According to Armin Biermann's thesis, censorship is virtually a "consequence of writing", which emerged 5,000 years ago, motivated by the "need for stability and control of communication". While a change in censorship is considered at least probable for the genesis of literacy, it is undoubtedly proven for the second focal point, Gutenberg's media revolution. Censorship gained in importance for political and ecclesiastical rulers with and due to the mass distribution of printed writings. They reacted to the publishing activities of the reformers, especially Luther, with restrictions. Censorship became a political instrument that became increasingly institutionalised and professionalised over time, from Metternich's surveillance state to the totalitarian censorship apparatuses of the Nazi state and the communist regimes of the 20th century. The most recent media upheaval is the shift to digital communication - which is once again bringing about massive changes in censorship, its forms and structures.

It would be wrong to perceive communication (or more narrowly: literature) and censorship in history as monolithic blocks that represent a pure pair of opposites of light and darkness. Heinrich H. Houben, an early censorship researcher who became famous above all for the wealth of anecdotes in his publications, put it this way in relation to the 19th century Vormärz: "The struggle of literature with censorship, as it was once practised in Germany, is the eternal clash of two world views, the struggle of light against darkness, of enlightenment against obscurantism." This thesis of a dualism between the light of free-spirited literature and the darkness of restrictive censorship, between good and evil, cannot be generalised. Historically, it is more appropriate to recognise the dialectic of the interrelated and mutually defining cultural phenomena of communication and censorship.

From the Reformation until well into the 18th century, censorship was by no means seen as something bad or negative. Rulers and subjects alike generally saw it as the necessary basis for living together in security, peace and order - from which troublemakers and disruptive factors could be excluded via censorship. Even most Enlightenment philosophers continued to regard censorship as an effective means of controlling communication, now used in their favour, for example with the aim of combating old-faith church positions, but also useless and uneducational (entertainment) literature.

In the Metternich era, on the other hand, the ambivalent attitudes of intellectuals towards censorship and their numerous points of contact with institutionalised censorship (quite a few writers were censors themselves) argue against a simple black-and-white scheme. By the modern age at the latest, however, censorship had completely lost its positive image: it became a taboo. No society, no state, not even dictatorships and autocratic systems, are open to its use.

Censorship terms

In all these attempts to understand the relationship between communication and censorship, it is important to know exactly what is meant by censorship. This is because there is no universally valid definition and, accordingly, no "generally established paradigms and accepted analytical instruments for working on censorship". Instead, in common parlance as well as in research, there is a broad range of what is understood by 'censorship', ranging from a formal to an informal concept of censorship. Formal censorship generally refers to the control of expressions of opinion by the state, or at least by an authoritative body, on the basis of regulations, administrative and criminal law provisions and measures; informal censorship refers to control that is not exercised by authoritative bodies, but by other social and individual pressures, such as economic, political and psychological pressure.

It is not surprising that such an informal concept of censorship blurs the boundaries with other forms of social communication control and monitoring. In general, the semantics of censorship are characterised by a certain vagueness. Beyond this scale of narrow to broad understanding of censorship, a quasi-referenceless concept of censorship can be perceived, a concept that is decoupled from the facts themselves. By this I mean the censorship polemics omnipresent in politics and the media, art and culture, in which censorship becomes "an inflationary polemical battle term". And always when there is a dispute about the limits of what can be said.

It is not only right-wing populists who repeatedly use the concept of censorship in their skilful scandalisation and self-victimisation strategies to reject criticism of inhuman and discriminatory statements. Anti-discriminatory taboos, protests and boycotts - keyword Cancel Culture - are also often labelled as 'censorship' in social debates. The constant polemical use of censorship as a fighting term generally leads to it being worn out, weakened and semantically shortened.

"Censorship shall not take place." (Art. 5 para. 1 GG)

To take a closer look at the formal concept of censorship, let us look at the prime example found in the German constitution, Article 5 of the Basic Law. The ban on censorship laid down here safeguards the basic civil right to freedom of opinion. It states: "Everyone shall have the right freely to express and disseminate his opinions in speech, writing and pictures and to inform himself without hindrance from generally accessible sources. Freedom of the press and freedom of reporting by radio and film are guaranteed. There shall be no censorship." (Art. 5 para. 1 GG)

According to the prevailing legal opinion, 'censorship' here refers to the state's preliminary examination of an expression of opinion intended for publication.

Such a narrow concept of censorship, which only covers state pre-censorship, ignores numerous phenomena of communication control and restriction. It is therefore not useful for historical censorship research, firstly because of its anachronism and secondly for factual reasons. For not even the comprehensive systematic regulation of literature that the Catholic Church exercised for centuries with instruments such as the Index librorum prohibitorum could be described as censorship according to this understanding. If Rome were to reintroduce the index today and ban tens of thousands of books from church members, this would not be censorship according to the German Basic Law - precisely because the state is the only 'opponent' it is supposed to protect against. Fundamental rights are rights of defence against the state, according to the famous formulation in the so-called Lüth ruling of the Federal Constitutional Court of 15 January 1958.

There are other critical questions that can be asked about the narrow concept of censorship in the German constitution. In times of global digitalisation, in which internet companies exercise comprehensive control over discourse, in which filter bubble technologies and company rules of procedure guide communication, the real threat to freedom of expression no longer necessarily seems to come from the state - at least not in democratic constitutional states. In this new situation, legal scholars are therefore discussing the question of the so-called third-party effect of Article 5 of the German Basic Law on non-state institutions, e.g. private companies. Incidentally, the aforementioned Lüth judgement had already raised the question of the indirect third-party effect of the Basic Law and emphasised the spill-over effect of fundamental rights, in the spirit of which all norms should be exercised in a constitutional state.

So the question is: should censorship be prohibited not only for the state, but also for other players? However, such a demand for less control of communication on the internet is in stark contrast to another major problem of our time, namely law enforcement in the digital space. In order to be able to enforce laws digitally, the controversial "Act to Improve Law Enforcement in Social Networks" (NetzDG) has been in force in Germany since 2017. It imposes comprehensive monitoring obligations on the major internet providers, which undoubtedly strengthens digital communication control. This context also includes the "Act to Combat Right-Wing Extremism and Hate Crime", which has been in force since 2021 and includes reporting obligations for internet providers. This is because it is not only communication control that jeopardises freedom of expression, but also, according to the official justification, precisely its opposite: on the internet and especially in social media, legislators are observing an increasing brutalisation of communication, which in turn jeopardises freedom of expression.

Censorship materialises everywhere

If we define censorship not only as the exercise of political power and state-authoritarian rule, but in a broader sense as any kind of communication control, formal and informal, private and public, then we must realise that freedom from censorship does not exist. In this broad understanding of the term, censorship is not only omnipresent in pre-modern feudalism or in current dictatorships, but always and everywhere, it is "inevitable, no matter the socio-political context". In democratic constitutional states, too, it appears in this sense not as a special case, but as the rule of human culture. Robert Post explains: "If censorship is a technique by which discursive practices are maintained, and if social life largely consists of such practices, it follows that censorship is the norm rather than the exception. Censorship materialises everywhere".

The socio-political concepts of Michel Foucault and Pierre Bourdieu were particularly influential for a broad semantics of censorship. In his research, Foucault focuses on social exclusion processes, "procédures d'exclusion", which control, select and organise discourse; in this way, he makes hidden repression visible. The post-structuralist censorship research inspired by him, which has been taking place since the 1990s and for which Post's cited anthology Censorship and Silencing became a standard work, is also known as New Censorship (Theory). The focus is on relationships between discourse and power, and between language and restriction.

Censorship research experienced a noticeable upswing as a result of New Censorship, but there was and still is criticism of such a broad, overly vague concept of censorship. According to Biermann, it is "academically useless", as it encompasses almost "every act of selection" that "makes something the subject and leaves others on the horizon, i.e. 'censors'"; in such an understanding of the term, censorship and society become identical, so to speak. Researchers working on historical-empirical issues in particular criticise the broad concept of censorship as "almost meaningless, but in any case largely inoperable from a scientific point of view" and warn against an "inflation and emptying of the term". Moore, on the other hand, emphasises the advantages of a broad understanding of censorship, which not only takes into account the omnipresent global censorship of states, but also soft censorship provoked by external pressure, not least self-censorship.

Phenomenology of censorship

It is a great challenge for researchers to systematise and categorise the phenomenon of censorship. Precisely because a variety of definitions and conceptual understandings exist, it is hardly possible to establish a transhistorically and transepochally valid phenomenology of censorship. In a first attempt, only the components of such a censorship phenomenology are listed here: the subjects, objects, means, functional locations and motives of censorship.

The subjects of censorship can be defined as those political and social actors and bodies that exercise control over communication. Depending on whether one takes a formal or informal concept of censorship as a basis, these include institutions such as the state and church, authorities, but also other social groups such as educational institutions, interest groups or political movements, the market and, in the case of self-censorship, the individual. Censorship objects are oral and written, acoustic and visual expressions that are affected by censorship, but also the people associated with them - e.g. writers, but in principle all members of a society - institutions (publishing houses, broadcasting organisations, press organs), media (print, film, television, internet) and objects (works of art, books, other data carriers) that are affected by censorship.

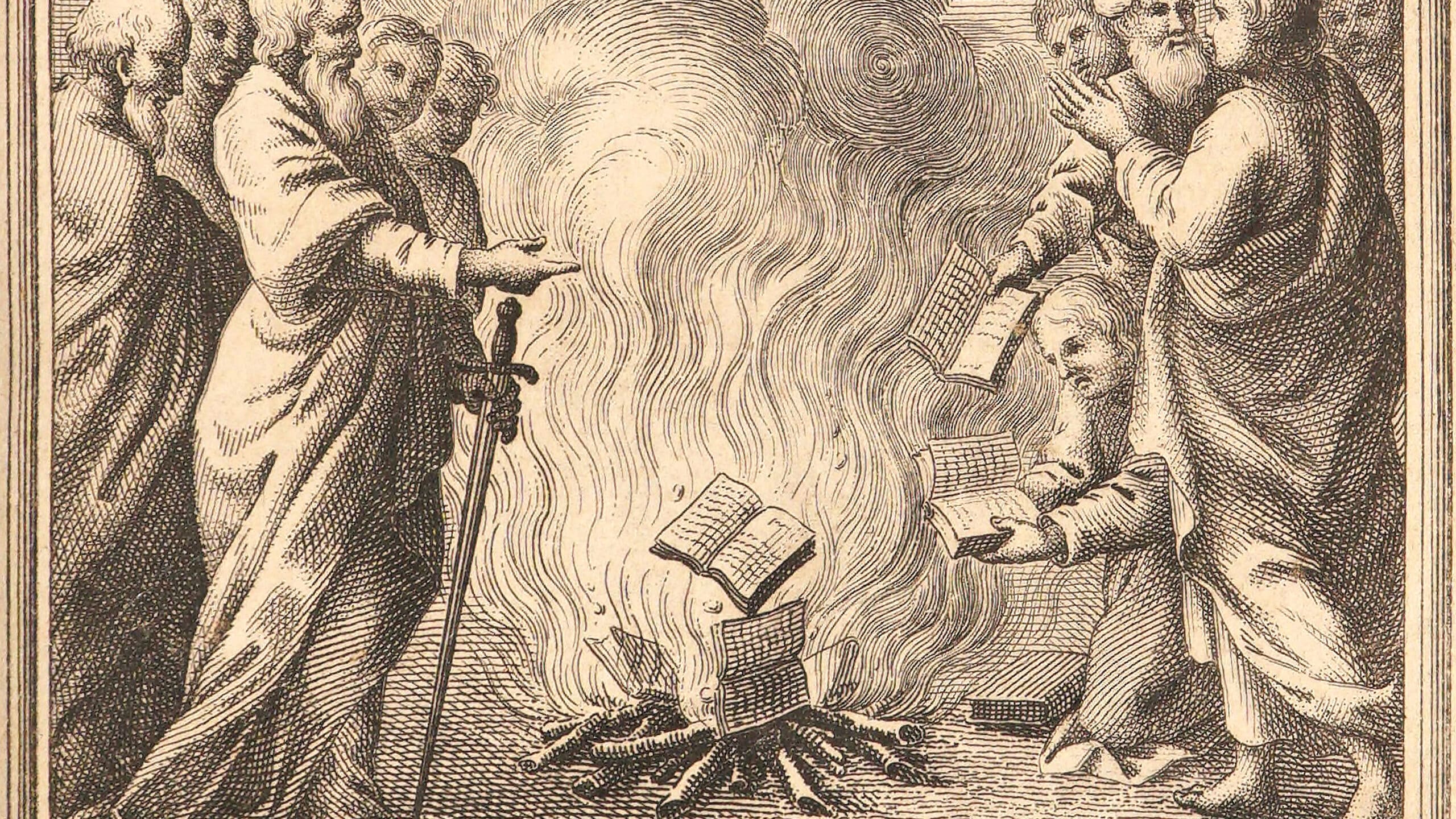

The procedures, techniques and strategies used by the subjects of censorship can be described as means of censorship. These include official bans, official decrees and indices (the Index librorum prohibitorum was mentioned), book burnings and censorship cancellations as well as digital blocking and deletion. In the context of an informal concept of censorship, economic damage, boycotts, occupational bans and various other means of controlling communication are also categorised as means of censorship.

Three special functional locations - or "break-in points" - of censorship can be identified in the communication process, according to the socio-historical triad of production, distribution and reception of literature: firstly, censorship can relate to the production of statements, i.e. target authors. Secondly, it can concern the distribution, i.e. the distribution and dissemination of statements, for example by publishers, platform providers or other media providers. Thirdly, censorship is aimed at the reception of statements by sanctioning reading or defaming circulating expressions of opinion.

Finally, censorship motives are the reasons for censorship. Some of these are put forward by the subjects of censorship themselves, for example when early modern rulers emphasise the need to control communication in order to maintain order, security and peace. In some cases, motives can only be inferred indirectly from censorship activities; for example, powerful motives such as the preservation of power are not explicitly formulated by rulers themselves. Research, going back to Otto, identifies religious, moral and political motives as the most important censorship motives. Remarkably, precisely these three can be found in the title of the electoral Bavarian censorship catalogue of 1770, Catalogus verschiedener Bücher, so von dem Churfl. Büchercensurcollegio theils als den religionswidrig theils als den guten Sitten, theils als den Landsfürstlichen Gerechtsamen nachtheilig verbotenhen. The protection of minors, a censorship motive that can already be traced back to the Roman Republic and has been particularly prominent since the 18th century, should also be mentioned.

These listed components of a censorship phenomenology, censorship subjects and objects, censorship means, places of function and motifs, form a complex structure of relationships whose relations can be described on a syntagmatic level (e.g. between the censorship carriers and their methods) as well as on a paradigmatic level (e.g. between the censorship motifs of different epochs).

Manual project

Soon, Nomos Verlag will be publishing a handbook edited by me entitled Zensur. Handbook for Science and Studies - a publication that is particularly relevant in the current situation. It has already been emphasised that the topic of censorship remains virulent in our present day. In particular, the enormous presence of formal state censorship is more evident to us today than ever before. Current crises, especially in view of the brutal suppression of freedom of expression in the Russian war of aggression, are not about hidden mechanisms of oppression in language, culture and society that could be tracked down in the Foucauldian sense; nor are they about cultural and political debates on what can be said in a democratic constitutional state. What we are currently witnessing is censorship in its harshest, most brutal form, formal state censorship.

This makes the resulting censorship handbook much more political and controversial than such handbook projects usually are. They usually bring together the latest research in order to create a standard work for academics and students. Of course, this is also the aim of our handbook. At the same time, however, it repeatedly ventures from academic research into highly topical political constellations on which it positions itself. This is particularly evident in the comments on Russia and China, but also on 'wild censorship' in South and Central America.

Finally, a few remarks on the structure of the handbook are permitted: at the beginning there are conceptual and theoretical basic articles as well as analyses of censorship in the major fields of politics, religion and business, art, media and law. The presentation of the historical epochs of censorship from antiquity to the 21st century is followed by a section in which we attempt - for the first time, incidentally - to take the global dimension of censorship research seriously: Each continent is presented in terms of its censorship history and present. Finally, current controversies and polemics are analysed, from so-called cancel culture, identity politics and cultural appropriation to right-wing populism and conspiracy theories.