Prisoner of war was a central experience of the Seven Years' War. Many thousands of people went through it. As an important mobility factor, it also carried the war into regions not directly affected by the fighting. The cartel system for ransoming or exchanging prisoners on the basis of bilateral contracts was characteristic of the handling of prisoners. Europeans who lived through the war with its heavy losses emphasised the humane treatment of prisoners of war as a special feature of their time. These included the Württemberg military lawyer Rudolf Friedrich Stockmayer (1738-1793). In general, the fate of "prisoners of war in modern times is infinitely better than before". There were examples of "warring parties competing to outdo each other" in their politeness towards prisoners of war.

Such actions are the "true hallmark" of truly great heroes. Stockmayer explained his judgement primarily on the basis of historical comparison with antiquity. It is implicitly clear that only the European principalities can be meant by the warring parties. In 1761, a clergyman expressed himself more clearly in a word of comfort to prisoners of war: "By all this, fellow prisoners, you know that the sword will not deliver you into barbarian hands, which will rob you completely and cut you to pieces, as barbarians are wont to do in the West Indies. You wear the chains of one of the most honourable peoples of Europe, and for how long?"

These words were written by Pastor Gerhard Philipp Scholvin (1723-1803) from Hanover. In a kind of pastoral ABC of the war, he also addressed the soldiers who had been captured by the French. Scholvin describes the behaviour of the civilised enemy in an appreciative manner and contrasts it with the 'non-European barbarians'. Peoples far removed in time or space could hardly disagree with these judgements. The widely read author of a key work on international law made a similarly favourable assessment of intra-European practices.

According to the Swiss Emer de Vattel (1714-1767), it was to the honour of the European nations that they rarely treated prisoners of war badly. The English and French, "these magnanimous nations", deserved praise based on reports of their good treatment of prisoners of war. His popular success Le Droit des Gens, published in 1758 in a practical pocket-sized format, was widely read during the Seven Years' War, especially among officers. Despite the Solomonic judgement of the English and French, Vattel subtly points out the direct competition between the European principalities and their generals and officers in the matter of prisoners.

On the one hand, it was about the honour, prestige and glory of the rulers, their armies and their nations. On the other hand, it was about individuals who could set examples of generosity, courtesy and philanthropy. In doing so, they gained social capital and had the opportunity to act in accordance with their personal values (which is not always easy in war).

The inner-European judgements of contemporaries on the treatment of prisoners listed here were often received uncritically by historians in the past. This was based on the experience of the Napoleonic Wars and the two World Wars, whose standards cast the past in a milder light. More recently, however, the myth of the limited warfare of the 18th century has been thoroughly deconstructed, as a result of which such source statements appear to be misperceptions that trivialise war. This underestimates the contemporaries. It would be naïve to believe that Stockmayer, Scholvin and Vattel did not know that prisoners of war also suffered greatly during the Seven Years' War.

An attempt must therefore be made to understand the three statements against the background of their time. We will therefore ask what information contemporaries received about the treatment of prisoners of war in antiquity and how they evaluated it. This will also be done with a focus on non-European war cultures in the colonial theatres of war of the Seven Years' War. Finally, the characteristics of European captivity will be analysed and the practices that were considered humanitarian achievements in their time and conveyed a sense of superiority will be examined.

Fascination and horror: A look at antiquity

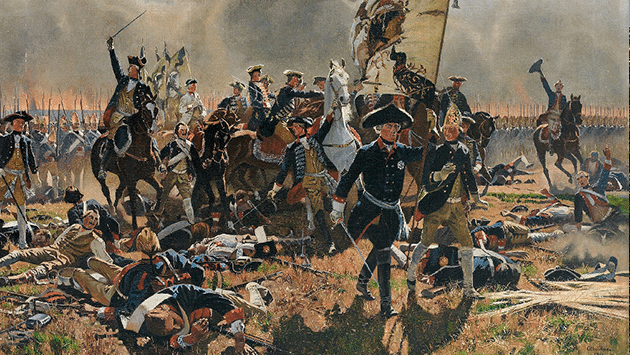

One of the most important historical points of comparison for the treatment of prisoners of war during the Seven Years' War was antiquity. The close connection between the Seven Years' War and recourses to antiquity is probably best manifested in the illustrated dedication of a Complete Roman History printed in Frankfurt in 1761 to the French Marshal Victor-François de Broglie (1718-1804). The victor of the Battle of Bergen (near Frankfurt am Main) in 1759 is placed by engraver Jean Conrad Back, like an equestrian statue, on a pedestal with an antique-style inscription in front of a topographical and analytical depiction of the battle. While the French and Allies meet on the field of honour on the dedication page, the Romans and Carthaginians cavort inside the book.

The Roman historians mentioned in the work were an elementary part of the educational canon for aristocrats and bourgeois contemporaries of the Seven Years' War, especially for officers. The second central point of reference, also for the general population, were biblical texts. Even ordinary soldiers were familiar with the war customs of antiquity through the Old and New Testaments. Antiquity initially offered general examples: contemporaries creatively appropriated aphorisms from biblical and ancient texts and applied them to their own situation. In the Old Testament, for example, a soldier from Brunswick, faced with capture, said that it was better to fall into the hands of the Lord than into the hands of the enemy (2 Sam 24:14). A Methodist clergyman in England also referred to the Old Testament when addressing French prisoners (Exodus 23:9): "Ye shall not oppress the stranger: for ye know the heart of the stranger, that ye were strangers in the land of Egypt".

In addition, contemporaries referred to great Greeks and Romans, especially generals and rulers. These included Alexander the Great (356-323 BC) in particular, who was popularised in the 17th/18th century through visual media as a magnanimous victor. The five-part Alexander cycle created in the 1660s by the French court painter Charles Le Brun (1619-1690), which was reproduced in the form of tapestries, copperplate engravings and even fans and thus found its way into many German residences, was characterised by positive set pieces on the treatment of prisoners in antiquity. Two of these five common depictions deal with the virtues of 'magnanimity', 'kindness' and 'self-conquest' when dealing with (high-ranking) prisoners. Originally, they primarily served as panegyric for rulers and conveyed a political and artistic programme, but could also be read by nobles as a model for dealing with fellow prisoners.

The painting Le tente de Darius shows how Alexander mercifully treats the captured family of the Persian king Darius after the Battle of Issus in 333 BC and was particularly well received during the Seven Years' War. A painting of the capitulation of Montreal in 1760 transfers the composition to the present day and depicts the British general Jeffrey Amherst (1717-1797) in the costume of his time as the second Alexander. It was commissioned by the owner of the Vauxhall Gardens amusement park. King Frederick II of Prussia (1712-1786) also commissioned a version of the scene from the famous painter Pompeo Battoni (1708-1787) in Rome immediately after the end of the war in 1763. This prisoner episode did not depict the wealth of ancient historical tradition about Alexander, but was a deliberately chosen set piece that symbolised magnanimity as a virtue.

However, the numerous ancient role models could also be surpassed in terms of virtue, for example by questioning their behaviour and war customs towards the defeated. An anecdote circulated about King Frederick II of Prussia after the Battle of Roßbach in 1757. In Merseburg, a severely wounded French marquis had said to the Prussian king during a visit to the wounded, captured officers four days after the battle: "O Sire! [...], how far they surpass Alexander! He martyred his prisoners to death, but you pour oil into their wounds."

This probably apocryphal exclamation shows that for the contemporaries of the Seven Years' War, antiquity also provided many negative, even irritating examples of the treatment of prisoners. The Württemberg auditor Stockmayer wrote that even the "civilised peoples of antiquity", even the "otherwise so wise and noble-minded Romans", had kept prisoners of war in a "harsh and slavish condition". The "ancient Germans", i.e. the Germanic tribes, also treated their prisoners of war in the most cruel manner and usually executed them.

The mass enslavement or killing of enemies well after they had been captured was highly reprehensible according to the custom of war in the mid-18th century. Auditeur Stockmayer also found the Roman custom of displaying and humiliating prisoners in triumphal processions and thus presenting themselves as "haughty conquerors" to be condemnable. From his perspective, Christianity brought great progress in the following centuries in that prisoners were no longer enslaved, but "the world became more reasonable and magnanimous in this respect" and they were only kept in custody.

The author of the Complete History of the Roman Empire paints an even more vivid picture of the "unheard-of cruelties" of the Romans and Carthaginians against each other. The Carthaginians would have used Roman prisoners of war instead of wooden rollers to launch ships, crushing them in the process. The Romans, on the other hand, would have locked Carthaginian prisoners of war in narrow boxes with nails pointing inwards and slowly martyred them to death. Many contemporaries of the Seven Years' War were particularly shocked by the disregard for class distinctions in antiquity, as there were few privileges even for captured leaders in the ancient world. The proof of Alexander the Great's inferiority compared to Frederick II of Prussia was that after his capture, the Macedonian king had a Persian commander - the equivalent of an 18th century staff officer - tied to a wagon and dragged to death. In this context, it was not about the ordinary soldiers at all.

The changing customs of war even made some of the ancient texts almost incomprehensible: a good example of this is the fable The Captive Trumpeter by the Greek poet Aesop (6th century BC), which has been retold in numerous variations. In it, a trumpeter is first captured after losing a battle and is then to be killed: "Gentlemen, says he, Why should you kill a Man that kills nobody?" His overcomers harshly reject this and get down to business, because he may not have fought, but he called for a fight.

During the Seven Years' War, however, trumpeters and drummers were rarely killed, but played an important role as parliamentarians and were allowed to pass through enemy posts unmolested in this capacity. They were central to communication between the warring parties, especially for the exchange of prisoners. In a commentary on the fable, this logical error is logically resolved from the perspective of a European war culture by placing the fable in a civil war context and making the exceptional killing of the trumpeter after his capture appear legitimate in this context.

Another version transposes the action to the present day and changes the constellation of characters to make it easier to understand. The trumpeter, who belongs to a 'regular' unit of some French "Gens d'Armes", falls victim to a band of light troops, namely hussars. Acts of violence by light troops were typically tolerated in the skirmishes of the Little War and were based on a culture of violence centred on booty and autonomy. Trumpet-murdering hussars appeared comprehensible as acting figures due to the bad reputation of these troops. Other commentaries bypassed the problematic content by not even attempting to make references to everyday warfare and understood the moral lesson entirely metaphorically.

The violence used against prisoners in the ancient texts both repelled and fascinated Europeans. Wasn't it tempting to take revenge on the vanquished - like the Parthians on their defeated general Crassus? The secretary to the commander-in-chief of the Dutch army, Martin Albert Hänichen (1707-1786), who came from Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, resented the French army that had occupied his fatherland at the beginning of the war. In the spring of 1758, he fantasised that the King of Prussia and the Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel should force the French prisoners of war to perform forced labour to repair the war damage in Wolfenbüttel and Halberstadt: "Ancient history provides us with such examples. And I must confess to you that I wish nothing but shame and confusion for the people who treated our innocent fatherland so cruelly."

The general Ferdinand von Braunschweig (1721-1792), who was otherwise known to be virtuous and humane, issued secret orders to threaten his approximately 7,500 French prisoners of war with a Roman-style decimation in the face of a suspected prisoner uprising. Neither statement was publicised, probably because the first revealed a lack of self-control and the second brought scandalous cruelty within the realms of possibility.

Contemporaries compared what they found in ancient texts with the non-European world and thought they recognised it in supposedly 'raw nations', such as the 'American savages'. The comparison between antiquity and the present in one of the most important encyclopaedias of the 18th century is significant. A "similar harshness" can still be found in "savage nations" today. For example, "the Negroes would not accept ransom money for a prisoner of war." The question arises as to what information Europeans had about the treatment of prisoners in other parts of the world and how they processed it.

(Colonial) horror stories: Prisoners of war in European media

As with the Europeans, the treatment of prisoners by the indigenous population of the Americas was subject to concepts of order. European war practices were not aimed at capturing as many opponents as possible, but at strategic success and similar abstract goals and were therefore more deadly. After capture, however, the lives of the conquered were more strongly protected. Women, children and the elderly were usually excluded from captivity. The high degree of organisation also made it possible to transport and hold larger numbers of prisoners.

For Native Americans, on the other hand, capturing live prisoners was an important war aim. The captives were regarded as individual property and could be adopted or sold to Europeans for ransom. A much smaller number were killed by ritual torture. Captured scalps also brought prestige, but were not regarded as equivalent to living prisoners. The independence and loose organisation of war campaigns by the First Nations, on the other hand, posed a greater threat to the lives of prisoners.

Warrior groups killed prisoners on the way back if they were physically unable to cope with the long distances. The mutual understanding between Europeans and First Nations for the respective concepts of order and practices in dealing with prisoners was poorly developed. Overall, Europeans tended to view other cultures of violence with disgust from an arrogant position and overlook their inherent logics.

This is reflected in newspaper reports on the treatment of prisoners. A copperplate engraving entitled Hinrichtung eines Kriegsgefangene bey den Wilden (Execution of a prisoner of war by the savages) from 1756 is representative of countless imagined atrocities committed by Native Americans against prisoners. Such atrocity reports reached the media centre of Hamburg via British communication channels in particular and were disseminated in the Old Empire in the form of newspaper reports, among other things. This can be traced back to the Hamburg Correspondent, which was one of the most important European newspapers at the time of the Seven Years' War and was managed by the widow Wendelina Sophia Grund.

In accordance with the understanding of neutral reporting at the time, submissions from all (European) warring parties were included, very explicit war propaganda was not printed and no interpretations of the reports were provided. The transgression of European norms was marked in the texts by references to the looting, killing or mutilation of prisoners of war, especially women and children. Central media events included the Battle of Monongahela and the massacre at Fort William Henry.

However, small reports of events that are no longer familiar today were also important for European imaginations of the indigenous treatment of prisoners in America. For example, a message received from London in 1761 drastically stated that the Cherokee "threaten to murder all white people who are their prisoners of war". The recipients were able to form their own opinions on the basis of these articles, but in the case of non-European peoples, there was naturally a lack of submissions from the opposite side as a corrective to British news.

The picture of the treatment of prisoners on the Indian theatre of war was gradually better, but the newspaper reports were nevertheless also characterised by atrocity reports. The recipients received one-sided news about war and captivity, which stereotyped Indian commanders and fighters as victors and vanquished according to the topoi of oriental tyranny and deviousness. As overcomers, their cruelty was shown in the episode of the Black Hole of Calcutta, where British prisoners of war were crammed into a room that was too small and thus killed.

The British narrative was disseminated in the Old Empire through an illustrated book series that was politically close to the Habsburg-Bourbon opposition. There, the Indian "tyrant" locked the British prisoners in the "black dungeon", "but only 23 people came out of this hellish pit, despite the fact that 146 people were inside."

Even in defeat, 'the Indian prisoner' was portrayed as devious. The Hamburg Correspondent reported on a cenotaph in Westminster Abbey dedicated in 1763 to a British vice admiral who had died in India. The newspaper states: "The admiral is depicted in life-size, [...]: his face is turned towards a beautiful woman, who [...] thanks the admiral for saving her from captivity, and underneath is written: Calcutta liberated [...]. On the other side is the image of a captured Indian, who is tied to a post with a chain and casts a sad, yet hateful glance at the admiral."

In addition to the Indians and Indians as non-European barbarians and semi-civilised people, contemporaries also saw barbarians on the European periphery, such as Cossacks, Kalmyks, Pandurs, Croats and Scots or even Portuguese peasants. The latter allegedly cut off the noses and ears of Spanish soldiers and were massacred as prisoners in return.

The newspaper articles legitimised European violence against those marked as 'different', parallel to the attribution of barbarism: one submission from London reports on an expedition against the Cherokee in which four Indian villages were destroyed: "200 houses were surrounded by the colonel in the night, and all the men found in them killed with the bayonet." According to the report, however, the Indian women and children were left alive by the British troops and made prisoners while they burned down the settlements. According to the report, the commander of the troops, Colonel Archibald Montgomery (1726-1796), would even have gladly spared the last village of Sugar Town and its "inhabitants" "if he had not attacked them at the very time they were roasting one of the white people on a spit." This report was not fictitious, as the British found at least one mutilated body in Sugar Town, but it failed to mention that the troops in the villages had also slaughtered women and children until the officers intervened.

European recipients thus received a distorted message that justified the transgressive behaviour of the troops, which would have been difficult to legitimise in the European theatre of war, by focusing on the alleged cannibalism of the Native Americans. It is also striking that in the thirteen colonies, the provincial government of Pennsylvania even minted medals commemorating the destruction of an indigenous village for the officers involved.

Similar legitimisation strategies can also be found in the reporting on one of the largest slave revolts in the Caribbean on the sugar island of Jamaica, Tacky's Revolt in 1760. In the newspaper reports, the alleged cross-border violence of the African slaves allowed for the enormous violence of the European-colonial plantation owners: if the "rebels", who according to the newspaper report fought cruelly, were captured, then "they are hung alive on the gallows for 6 to 8 days until they crepire from hunger, thirst and heat". The negative image of captivity in the non-European world was also reflected in everyday warfare by the fact that non-Europeans were actively marginalised from the prisoner of war system. On the sugar island of Martinique, the French had mobilised and armed free blacks against the British and requested prisoner of war status for them during the surrender negotiations. However, the British favoured enslaving all "Negroes taken in arms". This makes it clear that prisoner of war status was primarily granted to Europeans.

For the recipients of the reporting on captivity in the Seven Years' War, on the other hand, differentiated information was more readily available for the European theatre of war. The Swiss scholar Emer de Vattel was quoted in the introduction, who wrote that Europeans "rarely treated prisoners of war [...] badly". The qualification "rarely" already reveals that there were many controversial and contested events involving prisoners in Europe too. These included the incorporation of the Electorate of Saxony's army, which had taken prisoners of war at Pirna, into the army of Frederick II of Prussia in 1756. There was also controversy in the print media about the refusal of parole in battle, the failure to honour surrender treaties and assaults on prisoners.

During the war, the British government and public repeatedly defended themselves against the accusation of poor prison conditions for the French prisoners and, conversely, accused the French government of lacking a sense of responsibility for its prisoners, as it was unable to pay for their upkeep. However, the tone between Prussia and Austria was much harsher in the final years of the war: In a Prussian pamphlet in 1762, the Prussian general, Margrave Karl von Brandenburg (1705-1762), made harsh accusations against the Austrian general Laudon (1717-1790): the war was being waged by the Austrian side "more often than not, as if by barbarian peoples [...], so that the prisoners of war were mutually put into complete slavery", as Prussian prisoners had been forced into Austrian military service by force.

It should be noted that the international law expert Vattel, the auditor Stockmayer and Pastor Scholvin, with their positive judgements on the treatment of prisoners of war in the Seven Years' War, probably did not mean to express that this treatment of prisoners among Europeans was always in accordance with the norm. If they were following war news, they must have been aware that the European warring parties were accusing each other of barbarism and that this in turn legitimised attacks on European prisoners of war. In comparison with what they had read in various media about the treatment of prisoners in antiquity or among 'unruly peoples', European practices appeared to them to be magnanimous or humane despite all the problems, so that they described their time as "infinitely better than before". Their standards were set low due to the imagination of a cruel antiquity and a bloodthirsty non-European world.

Captur - Replacement - Rifle on the shoulder: Prisoners of war among Europeans

Finally, the central characteristics of captivity in the European theatre of war will be outlined.

Negotiated capture was one of the most common. During the Seven Years' War, large bodies of troops were taken prisoner primarily as a result of the numerous capitulations, for example at Pirna in 1756, Breslau in 1757, Minden and Louisbourg in 1758 and Maxen in 1759. In the French-Allied theatre of war in the west of the empire alone, half of the 54 or so capitulation agreements ended in captivity. The path to captivity was generally organised as a military rite of passage. Defeated armies and garrisons marched out to the sound of music and with waving flags, marched past the troops of the victors standing on guard and laid down their arms. The surrender treaties often also regulated who became a prisoner of war and who did not, and granted the prisoners certain privileges, such as the protection of personal property. There was no clear distinction between combatants and non-combatants. Occasionally there were abuses during surrenders and individual articles of surrender were broken, but overall the wartime custom of 'surrender' worked relatively well.

Similarly important was the 'free capture', for example in the skirmishes of the Little War and the major field battles. Free capture was the most dangerous way into captivity. Humanitarian norms and the Christian ban on killing competed with tactical norms and the soldiers' will to survive. A silver medal depicts this fundamental problem of war. The figure of a French officer weighs up the law of war against the law of equity - ius belli versus ius honesti. It was common knowledge in the regulations of the time that one should only start taking prisoners when victory was certain. Accordingly, it was not considered a good character trait to refuse to capture defenceless enemies in battle and kill them, but it was not a particularly serious breach of the norm either.

At sea, the battle was signalled without mercy by raising the blood flag. In land warfare, 'no mercy orders' were issued and so-called cruelty battles were fought without taking prisoners. Similarly, in battle, soldiers would repeatedly fall into a kind of bloodlust and unleash their fear and rage in massacres of already defeated opponents. In the chaotic battle situation, however, it was not always easy to grant clemency, even with good intentions. Once the vanquishers had granted the vanquished pardon and granted them prisoner status, the life of the now 'real prisoner of war' was usually protected. This was the superior magnanimity of the Seven Years' War. Away from the battle zone, the chances of survival for prisoners were often good, if one disregards the general problems of 18th century warfare - supply crises and disease.

In the case of 'real prisoners', who had been granted European prisoner-of-war status by the victors after the battle, the spectrum of prisoner experiences was subsequently very broad.

When Vattel writes that the prisoners were "rarely treated badly by the Europeans", it is a priori difficult to apply this statement to the conditions of imprisonment in general. Prisoners of war ranged from barely perceptible virtual imprisonment on their word of honour to close confinement under the harshest conditions. The accommodation situation for prisoners was usually favourable if the principalities had a secure hinterland. This applied to the Habsburg Empire, Great Britain and France and, to a lesser extent, to Electoral Hanover.

In Great Britain, the Habsburg Empire and Electoral Hanover, there were 44,512 prisoners of war at any one time, spread across 62 towns and small cities. On average, just under 720 prisoners of war were housed in one place. This was in an acceptable proportion to the population of many towns in the 18th century, which often had between 1,000 and 3,000 inhabitants. However, long periods of detention and cramped quarters - the source term for the accommodation - could lead to high mortality rates among the prisoners due to epidemics such as red dysentery or dysentery.

the camp fever.

Great Britain, for example, regularly exchanged enemy land soldiers, but deliberately held seamen prisoner in above-average numbers and for an above-average period of time, namely until the end of the war, in order to weaken the fragile manpower reservoir of the French navy. In Prussia, the situation of the prisoners was even more precarious, although at least until the winter of 1759/60, prisoner replacements did materialise. The kingdom was threatened from all sides and therefore resorted to a small number of secure fortress towns, some of which were massively overcrowded as a result. These included Spandau, Küstrin, Stettin and Magdeburg as well as Merseburg and Leipzig. Especially for the Habsburg irregular troops, Croats and Pandurs, the

Living conditions here are catastrophic.

The fact that, on the one hand, captivity could claim many lives, but that this was not exclusively due to cruel treatment by the survivors, probably explains Vattel's positive judgement. The lives of soldiers in the camps and garrisons were similarly threatened by infectious diseases.

The common denominator of the prisoners' quarters in the cities was that there were no well-planned prison camps as functional buildings. The places of detention were all improvised. Buildings belonging to the respective sovereigns were often used, such as castles, palaces and barracks. This had the great advantage that there was rarely any resistance from the local population. The spectrum also ranged from communal buildings, such as schools and churches, to the homes of the subjects. The prisoners were kept in the places where they were housed and only in rare cases, such as in Canada, were they exploited for forced labour.

Instead, the prisoners employed themselves. There was also voluntary wage labour in the enemy's country, for example as workers in fortress construction or on estates. Individual prisoners sometimes integrated fully into the enemy's host society by marrying or acquiring citizenship. In this respect, the comparison of their own actions during the Seven Years' War with the enslavement of prisoners of war in antiquity was quite favourable.

If the prisoners had a roof over their heads, they also had to be provided for. In addition to pay, the basic needs of ordinary soldiers in captivity included food, clothing, straw for sleeping, candles for light and firewood for heating, as well as medical care from military hospitals. Accordingly, raising pounds, imperial thalers and ecus was central to the survival of the prisoners. The living conditions of the prisoners were positively influenced by the fact that the detaining powers often shifted responsibility to the prisoners themselves and their countries of origin. The prisoners' countries of origin were responsible for raising the money needed to meet their basic needs. French prisoners of war in Prussia and Electoral Hanover, for example, received their subsistence from Paris by means of letters of credit from Cologne bankers. The pay was paid by captured officers.

For organisational reasons, personnel from the prisoners' countries of origin were also taken in by the victors in a neutral capacity. In order to convert the remaining transferred money into payment in kind, the detaining powers allowed the presence of war commissioners from the other side as neutrals. The war commissioners concluded contracts with suppliers in enemy territory. The presence of enemies declared neutral is very interesting because it meant that the victor's treatment of prisoners was subject to observation, as was done in a different form by the International Red Cross in later conflicts.

In addition, the detaining powers also liked to outsource responsibility for 'policey', i.e. good order among the prisoners, to the officers and non-commissioned officers of the other side. In extreme cases, hardly any guards were present during prisoner transports because the captive officers had previously signed off on the number of prisoners and could be held responsible for fugitives. All of this saved the victor organisational and financial resources as well as manpower, while the prisoners benefited from the more lenient prison conditions and the presence of neutrals. It can also be concluded that it was not necessarily the detaining powers that treated their prisoners badly, but often the states of origin were unwilling or unable to provide their captured soldiers in enemy territory with sufficient pay, food and clothing.

In the 18th century, conditions of imprisonment according to rank were seen as a further civilising achievement compared to antiquity. The military jurist Rudolf Friedrich Stockmayer, quoted at the beginning of this article, even claimed that the opponents of the war sometimes engaged in a veritable contest of courtesies for prisoners. These courtesies were primarily extended to the officers, although the commoners were sometimes also granted favours and alms. It was a general rule that distinguished prisoners of rank were to be treated with distinction. The higher the rank in the military and above all in aristocratic society, the greater the honours.

There was, as Marian Füssel succinctly puts it, "a strict two-world division" between officers and privates in captivity, with non-commissioned officers receiving at least minor privileges. This clear division is clearly recognisable from the fact that physical captivity mainly affected commoners and non-commissioned officers, while the course through captivity was sometimes quite different for officers.

According to the 'Captur', captured officers were occasionally invited to the table of the enemy officers. A copperplate engraving from the early 19th century is representative of many contemporary text sources. The officers were entertained and some of their plundered swords and pocket watches were returned to them by the victors. When being transported to the hinterland, they did not have to walk, but travelled on horse-drawn carts or riding horses. They were usually assigned a town in which they could move freely on giving their oath of honour. Once there, they rented rooms or were given individual quarters. Officers were also often released on their word of honour to their home country or to health resorts and seaside resorts, whereby they only had to return quickly on request.

This virtual form of captivity was seen by European contemporaries as an important step forward in civilisation. Nevertheless, imprisonment could also be a negative biographical turning point for officers. The lower the officer's rank and nobility, the less privileged the position. This was particularly true for subalterns.

officers. In captivity, they often became heavily indebted and were also slowed down in their careers, which were primarily based on seniority, and in the worst cases were replaced by others. The hierarchies of rank were also quite fragile in captivity in a foreign country and could be challenged. Furthermore, from the perspective of the overcomers, norms for dealing with noble prisoners were in competition with norms for dealing with the enemy vilified in war propaganda, who had perhaps just devastated their homeland or killed their comrades. Moreover, it was not always possible to explain to the subjects why they should not treat the defeated enemy with malice and ridicule.

In addition to the international law expert Vattel, Pastor Gerhard Philipp Scholvin was quoted at the beginning as one of the most civilised peoples in Europe. With the rhetorical question "and for how long?", Scholvin refers to the often limited duration of captivity. This rapid release and replacement of prisoners was unusual to this extent in other war cultures. When soldiers were taken prisoner, they became part of a somewhat disruptive but frequently functioning circulation system. The prisoners were able to regain their freedom through cartels and conventions for the exchange of prisoners. These ransom cartels were the subject of extensive negotiations.

The contracts contained exchange rate tables for the officers and men of the armies in money and heads, specifications on the exchange rhythm (often every 12-13 days) and sometimes also on the supply of the prisoners. The exchange of prisoners only materialised when both sides believed that it was a zero-sum game. As prisoners of war caused a great deal of organisational effort, could pose a danger to the hinterland and there was no guarantee that their warlord would actually pay the advances for their upkeep, this zero-sum game was often an attractive option.

One side was also happy to enter into the deal if it believed it would gain an advantage. In many cases, the exchange deal collapsed quickly after the contract was concluded because the strategic situation changed, sometimes rapidly. The exchange of prisoners between the Austrians, Imperial Army, Russians and Swedes and Prussia worked particularly badly. On the one hand, this was due to Frederick II's calculating, sometimes cynical treatment of his prisoners, who used them as leverage in negotiations and showed a considerable willingness to escalate. On the other hand, Austria had recognised that the Prussian army was less able to replace the losses caused by captivity.

The Franco-British and Franco-Allied treaties, on the other hand, functioned relatively continuously. According to the cartel agreement concluded in Dorsten in 1760, the French and Allies even exchanged their prisoners until the end of the war. A special feature was that all prisoners, regardless of rank, were sent home to virtual captivity immediately after capture.

Negotiators and organisers were central to the creation and execution of the cartels. The fate of thousands of prisoners of war depended on the administrative skills of specialised military officials and the instructions of rulers and ministers. One example of this is the Lorraine war commissioner Pierre-Nicolas de La Salle († after 1792). During the war, La Salle constantly travelled with his carriage between the garrison town of Metz, the imperial city of Aachen, various French garrisons in the Rhineland as well as Emmerich, Dorsten, Frankfurt am Main and then to the headquarters of the opposing side - as far as Magdeburg, for example. He calculated the upkeep of the prisoners, maintained prisoner lists and carried out the exchange business.

In 1760, his prisoner negotiations even inadvertently triggered a false rumour about an imminent truce. The exchange business with its constant travelling demanded a healthy constitution and harboured dangers: La Salle fell seriously ill once and twice his carriage was captured by enemy troops. His busy activities are documented in German and French archives in hundreds of letters. Military officials who were barely recognised at the time, such as War Commissioner de La Salle, made the functioning of the cartel system possible in the first place.

How positive or negative was the experience of imprisonment for those affected? The result is ambivalent. In some of the prisoners' own testimonies, imprisonment is portrayed very negatively. Other sources, on the other hand, give the impression that this is a normal travelogue of the time or the diary of a flat-sharing community that was relatively content with everyday life. For some contemporaries, imprisonment was even a kind of positive key experience for their later lives. This was the case, for example, for the Croatian lieutenant and writer Matija Antun Relković (1732-1798) and the French military pharmacist and agronomist Antoine Parmentier (1737-1813). After returning to his homeland, Relković spread the culture of the French Enlightenment, while Parmentier popularised the potato as a foodstuff in France.

On the other hand, there were countless nameless Prussian prisoners who died of dysentery in the Habsburg Empire. Despite the sometimes mild prison conditions, being a prisoner of war was not a harmless experience. The prisoners were trapped in a kind of limbo while life went on around them. Requests for leave from prisoners give an insight into the family affairs that were missed for lack of attendance: Wives and parents sometimes died while the men were imprisoned, inheritance disputes arose with relatives, children were left behind. Letters offered a fragile opportunity to participate in the relationship networks, as evidenced by the emotional love letters from an Irishman imprisoned in Bayonne to his "sweetheart" in Dublin.

Janus-faced progress: The historical transformation of wartime captivity

The three source quotations on humanitarian progress in the area of captivity listed at the beginning are quite logical in view of their time and the information circulating in Europe. Generosity and humanity towards prisoners of war were important virtues for Europeans during the Seven Years' War. In earlier centuries, their treatment had not yet been so strongly moralised. Unsurprisingly, the European warring parties repeatedly failed in their own endeavours. As in our own time, there was a - sometimes considerable - disparity between aspiration and reality.

However, numerous violations of norms and the reference to competing norms should not obscure the fact that the chances of survival and the living conditions of prisoners of war improved slightly overall compared to earlier wars. If cruelty battles without pardon are cited as a counter-example, this is too short-sighted. The protection of prisoners of war began primarily after the battle with the 'real prisoners': this is where contemporaries located the humanitarian progress. For the so-called 'civilised European peoples', chaining was merely a metaphor.

As soon as they were taken away from the theatre of war, the prisoners of war had basic provisions and were rarely used for forced labour. Long before the International Red Cross inspected POW camps, neutral military officials and suppliers from their own side supervised the prisoners' conditions of detention. If an overcomer too clearly violated various existing norms, this could lead to a diplomatic incident or a media scandal. It was also very likely that the prisoners would be released, if not immediately, then after months or a few years through a prisoner exchange.

In addition, there is an aspect that is not immediately recognised as a humanitarian achievement, but which was extremely important to contemporaries: the distinction that was so important for the estate society was usually successfully maintained. There were no kings in chains. Europe would not experience this again until Napoleon's captivity.

Humanitarian progress could be demonstrated to contemporaries in a particularly glaring way by comparing it with the different war cultures of antiquity and various non-European peoples, whose internal logics were ignored. It was also important, perhaps even decisive, that the dark sides of European war practices were quickly forgotten when it came to captivity and exemplary acts of kindness were already remembered much more intensively at the time.

On closer inspection, however, these humanitarian advances prove to be Janus-faced in three respects:

1. the functioning cycle of captivity with the frequent exchange of prisoners helped to continue the war. Thousands of soldiers went through captivity, were reorganised as returnees, rearmed and then sent directly into the next combat mission. In extreme cases, particularly between the Allies and the French from May 1760 onwards, prisoners were back at arms after 10 days. This cycle made the war more bearable and prolonged it. The warring parties did not have to constantly deal with the high costs of maintenance and accommodation, prisoner uprisings and overpopulated improvised prisons. They could focus on the battles, sieges and skirmishes - the prestigious aspects of warfare.

2) Many people who fought in the Seven Years' War were not even granted prisoner of war status. These included rebellious slaves or armed peasants sent to guard borders. Instead, the self-attributed higher level of civilisation of European war customs could even be used to legitimise violence against others - i.e. ethnic violent actors such as Cossacks and Croats in Europe as well as Africans, Native Americans and Indians in the colonies. The Seven Years' War was certainly a time in which news of the cruel treatment of prisoners of war by non-European, barbaric or semi-civilised peoples was concentrated. From a European perspective, these people were at the developmental stage of antiquity in their treatment of prisoners of war. The problems inherent in this idea with regard to the wider colonial history are evident.

3. generosity, justice, politeness and humanity towards prisoners of war were weapons used by Europeans in the battle for sovereignty of interpretation in the war. The warring parties claimed moral victory on the basis of their kindness and courtesies towards prisoners. This "humanitarian patriotism" went hand in hand with a multitude of accusations against the hostile principalities - from breach of law to civilisation deficit to barbarism. The humanitarian competition between the warring parties could have a positive effect on the prisoners' conditions of detention if it manifested itself in a spiral of 'outdoing each other in politeness'. Conversely, reproach could also clash with reproach: The result was a failure of communication and a slide into a spiral of reprisals. This was particularly the case in Austria and Prussia. Here, the battle for moral superiority was fought at the expense of prisoners.